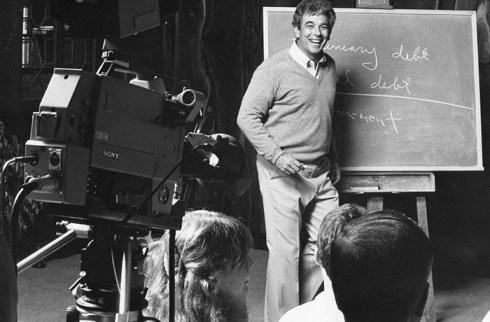

R.C. Sproul (1939-2017), on camera, recording one his many Ligonier conference sessions, back in 1985 (photo credit: Ligonier Ministries).

Robert Charles Sproul, known to most people as “R. C.,” was one of the most influential theologians in 20th/21st century evangelical Christianity. A primary architect of the 1970’s Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, and an outspoken critic of the 1990’s dialogue statement between evangelicals and Roman Catholics, Evangelicals and Catholics Together, Sproul was first and foremost a Bible teacher, whose passion was to help Christians integrate their thought life with the teachings of Scripture.

I first heard of R. C. Sproul when a friend handed me a set of cassette tapes, on the relationship between modern philosophy and Christianity. Sproul had given these talks at various retreats held at Ligonier Valley, a study center Sproul had founded, near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. As a young believer, I was blown away at how articulate R. C. Sproul was in addressing the type of intellectual challenges I was facing in college.

Not too many Christian Bible teachers were doing this at the time. R. C. Sproul was against efforts within the evangelical church to “dumb-down” the Gospel message. Every Christian, not just professional pastors, needed to know the basics of theology, and he had the gift of taking difficult theological concepts and making them understandable to the average believer.

R. C. Sproul had zero interest in God, and plenty of interest in sports, until he got to college. He became a believer in college, and eventually studied theology under John Gerstner, at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. At first, Sproul resisted the Reformed theology of Gerstner, making himself into a “pest,” but he gradually came around to Gerstner’s perspective. Later, Sproul pursued doctoral studies under the preeminent Dutch scholar, G. C. Berkouwer, in Amsterdam. The Ligonier ministry was moved to Orlando in the mid-1980s, sponsoring dozens and dozens of weekend and week-long conferences. He was able to pass the leadership of Ligonier Ministries, along with a magazine he had founded, Table Talk, and his Renewing Your Mind radio program and podcast to a new generation of teachers. Over his half century of ministry, R. C. Sproul lived a life of impeccable integrity.

As an ardent Calvinist, R. C. Sproul nevertheless had his critics. He left the mainline Presbyterian church (the PCUSA), over concerns of a drift towards liberal theology. He joined the younger, more conservative, Presbyterian Church of America (PCA) in the 1970s, identifying himself as an heir to the Reformed tradition of the 1648 Westminster Confession of Faith, to the chagrin of other evangelicals who would embrace “believer’s baptism” only, or elements of Arminian theology. Others criticized him for not taking a firm stand regarding the age of the earth, with respect to the doctrine of creation, while others accused him of holding to “replacement theology,” by his not taking a stronger stand to support national Israel’s role in biblical prophecy. He was drawn to taking a more preterist view of the Book of Revelation, that suggests that many events described in that book of the Bible have already taken place, to the consternation of many evangelical futurists, who see most of Revelation being fulfilled in the End Times. Sproul publicly rebuked the late theologian, Clark Pinnock, for the latter’s advocacy of the controversial doctrine of open theism. Some thought Sproul was too heady, in promoting theology, at the expense of practical spirituality. However, R. C. Sproul resisted pressures by other evangelical leaders, to make political statements, preferring to stick to his core themes of teaching Christian theology and apologetics.

It is fitting that R. C. Sproul would finish his earthly life in the year of the 500th anniversary of the start of the Protestant Reformation. R.C. Sproul loved to tell the story of Martin Luther’s encounter with Rome, generally marked by the year 1517, with Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses. Sproul saw in Luther’s theology the missing ingredient in much of evangelical thought and life today, a consciousness of the holiness and sovereignty of God. If there was one note that R.C. Sproul sang loudly and sang well, it would be to call the church back to God’s sovereignty and The Holiness of God, the title for perhaps his most important book.

R. C. Sproul was truly a man of the Reformation. He is remembered here at Ligonier Ministries, and with this obituary at The Gospel Coalition. Below is a video set of snapshots of Sproul, over the years, teaching on his favorite subject, the imputation of the righteousness of Christ (check out that head of hair!!).