Here is one of those Bible passages you probably never hear a sermon about:

50 But Jesus cried out again with a loud voice and gave up his spirit.51 Suddenly, the curtain of the sanctuary was torn in two from top to bottom, the earth quaked, and the rocks were split. 52 The tombs were also opened and many bodies of the saints who had fallen asleep were raised. 53 And they came out of the tombs after his resurrection, entered the holy city, and appeared to many. (Matthew 27:50-53, Christian Standard Bible)

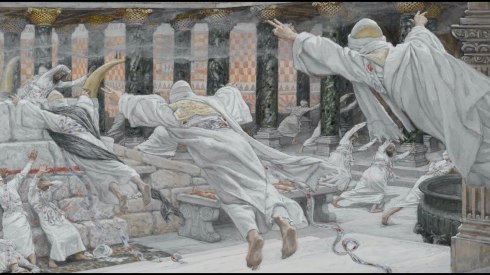

It is Good Friday. Jesus had just died, after being crucified on the cross. Verse 51 is loaded with interesting details, but the really weird part starts in verse 52. At first glance, it seems like something out of the 1968 movie, The Night of the Living Dead. Does this mean we really have “zombies” in our Bible?

... Another post in a series on “historical criticism” of the Bible. Go ahead and skip the video clip linked here, for The Night of the Living Dead, if you do not want to get freaked out….

A “Zombie” Apocalypse on Good Friday?

What makes this text all the more strange is the fact that only in the Gospel of Matthew do we have this story about the “zombies.” None of the other three Gospels even hint at this. You would think that the Resurrection of Jesus is a big enough event, but to have a whole group of raised saints wandering around Jerusalem would have really caused a stir. Where did they all go? What is going on here?

There are two basic ways of interpreting this passage: The traditional view suggests that this is an historical event that Matthew uniquely records. Yet trying to grapple with who these “saints” are, and what this all means, are both provocative questions.

The most common explanation is that these raised “saints” are Old Testament believers, such as some heroes of the faith, like the great prophets of the Old Testament, like Isaiah and Jeremiah, perhaps. Some tie this story of these raised “saints” with the Harrowing of Hell, commonly associated with the phrase, “He descended into hell/hades,” found in the classic early creed of the church, the Apostle Creed, which some suggest teaches that between his death on Good Friday, and his Resurrection on Sunday, Jesus is preaching the Gospel to those who have died, raising those who believe to new life.

The apocalyptic/metaphorical view suggests that this story in Matthew is not an historical event, but rather a type of prophetic vision of what will happen in the End Times, which is the reason why it is called “apocalyptic.” The appearance of raised saints points forward to the future, whereby all true believers in Jesus will be raised permanently to eternal life. While the apocalyptic/metaphorical view does not insist that this actually happened historically on Good Friday, it is nevertheless still true, since it is anticipating the reality of the future Resurrection.

Dr. Michael Licona, a New Testament scholar, and probably one of the most able defenders of the Bodily Resurrection of Jesus, against the skeptics who deny Jesus’ Resurrection, takes this metaphorical view. Dr. Licona came under severe criticism about ten years ago, or so, by suggesting that this story is an example of “special effects” added in by Matthew, to better explain the meaning of Christ’s death. Defenders of the traditional view say that inserting a fictionalized literary device smack dab in the middle of an historical narrative like this interrupts the flow of the story. But even more serious, Licona’s critics accused him of denying biblical inerrancy by “de-historicizing” this element of Matthew’s narrative.

So, which view is right? The traditional, historical view or the apocalyptic/metaphorical view?

A still frame from George Romero’s 1968 horror film, Night of the Living Dead. Matthew the Evangelist did not have this in mind regarding the risen dead that walked the streets of Jerusalem, following Christ’s Resurrection. But this peculiar incident in Matthew’s Gospel raises some interesting questions: Did Matthew mean this to be part of his historical narrative, or was this an apocalyptic metaphor, looking to the future?

Examining the Evidence

In classical debates about how best to interpret difficult passages like this, it is always the prudent idea to place the burden of proof on the non-traditional view. The traditional view, by the very fact that it has been embraced by Christians for a long period of time, even back to the period of the early church, should enjoy the favor of place in these type of discussions. It is up to defenders of the apocalyptic/metaphorical view to see if they can meet the burden of proof, in order to overturn the tradition.

Furthermore, defenders of the traditional view are concerned that the metaphorical view might call other miraculous events in Scripture into question. This is a very reasonable concern: Where do you draw the line here, and on what grounds do you make a distinction between an historical narrative account versus a prophetic, metaphorical vision of some sort? Jesus spoke in parables, which are fictional teaching devices, but the Gospels also claim that the Resurrection of Jesus is a real historical event, in space and time. The Bodily Resurrection of Jesus has the unanimous consensus from our New Testament sources, including all four Gospels. For if Jesus is risen from the dead, then this opens up the historical possibility of other miraculous Bible events having happened in history as well. But does this necessarily mean that the best explanation for another difficult passage requires a “miraculous” explanation? Another “non-miraculous” explanation, that fits the data better, might actually make better sense of the text. But does the evidence really support this? Traditionalists have a right to be worried, as some Christians, who find no difficulty in accepting the Bodily Resurrection of Jesus, will go to great lengths to dismiss other miracles, such as the Virgin Birth of Jesus, as a pious fiction, a view which causes all sorts of mischief.

From the perspective of an historian, one could argue that both the traditional and apocalyptic/metaphorical views are historical possibilities. Only those skeptics who reject the supernatural would rule out the traditional view as a possibility, because the idea of people walking around after being dead is most definitely a supernatural event. For some who employ the historical critical method, the impossibility of the miraculous is the starting point, and the divine inspiration of the text is an assumption that can be safely set aside, for the sake of getting at the “real” history. In other words, if you treat the miraculous with utter disdain, or you reject the concept of God-breathed inspired Scripture, then the whole business about Matthew’s Gospel “zombies” as historical event will probably just come across to you as completely silly. For historically orthodox Christians, the use of historical critical method does not require one to take those kind of skeptical steps.

However, it is not enough to determine an event’s possibility. What is more difficult is to try to determine how plausible an event might be, considering the evidence, and then try to weigh that evidence to figure out what view is more probable, compared to the other alternatives.

The sheer weight of tradition is not something to dismiss lightly. However, there are a number of factors to consider, that are frankly ignored or otherwise distorted by some commentators who defend the traditional view.

The first thing to consider is what did it mean for these saints to be “raised?” After all, Jesus himself had raised Lazarus from the dead (John 11:1-44). But was the raising of Lazarus the same as the raising of these saints on Good Friday?

Most scholars would agree that Lazarus was risen from the dead, but that he eventually died at some later time. You will be hard pressed to find anyone who believes that a 2,000 year old Lazarus is still living in some New York City high-rise apartment, collecting social security. Likewise, there are some who believe that these raised saints on Good Friday eventually died again, just as Lazarus did. Unfortunately, the text in Matthew does not tell us anything about the eventual fate of these raised saints.

If these saints who were raised died again, it does make you wonder what the point of the whole story was about. For if these raised saints were Old Testament believers, what would the point be for them to be raised, and then die a second time?

The other alternative would be that these raised saints remained alive after this event. Does this mean that a whole group of “zombies” are living in New York City apartments, collecting more social security, and making our taxes so high? Well, most probably not. Unfortunately, if these saints did remain alive, we have no record of an ascension of these saints (Though some do suggest that this is implied by another weird and difficult passage, Ephesians 4:7-10, and/or that these saints quietly ascended to heaven along with Jesus at Jesus’ ascension).

The real tricky part is trying to make this historical reconstruction of events fit with other parts of Scripture. Here is the Apostle Paul:

20 But in fact Christ has been raised from the dead, the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep…. 23 But each in his own order: Christ the firstfruits, then at his coming those who belong to Christ. 24 Then comes the end, when he delivers the kingdom to God the Father after destroying every rule and every authority and power. (1 Corinthians 15:20,23-24 ESV)

Some commentators say that the raised saints on Good Friday are some of the “firstfruits” of the resurrection promised to all believers. Some suggest that verse 23 above should have a comma after “Christ” but before “the firstfruits“, to therefore read: “But each in his own order: Christ, the firstfruits, then at his coming those who belong to Christ.” In other words, first Jesus is raised, then the “zombie” saints in Jerusalem, and then finally associated with the event of the Second Coming, everyone else is raised.

There are several problems here. To take verse 23, and divide it up into three separate events does not mesh well with verse 20, where the Resurrection of Christ, by itself, is equated with the “firstfruits” of the Resurrection. The answer to this objection is that “firstfruits” is plural, which would suggest that multiple events can be associated with these “firstfruits.” In other words, both the Resurrection of Christ AND the raising of these saints together are the “firstfruits.”

True, firstfruits is plural here, but this is a grammatical construction that can have a singular referent. A good example in English is the word mathematics. I majored in mathematics in college, but it does not mean that I double-majored, or triple-majored in multiple mathematic subjects. To say that I majored in mathematics is the same as saying that I majored in math, which is singular. I majored in one subject, mathematics. Likewise, it is perfectly consistent with the biblical text here to say that the (singular) Resurrection of Christ is equivalent to the (plural) firstfruits of the Resurrection. Furthermore, we can find another example of this singular referent to the plural firstfruits in a passage like Romans 16:5, where Epaenetus is described as the “first convert” (firstfruits) to Christ in Asia.

However, the most serious difficulty is that the order of events described by Paul here in 1 Corinthians does not mesh well with the traditional historical interpretation associated with Matthew. A number of commentators will say that in Matthew’s narrative that Jesus was Resurrected on Sunday morning, and then followed by the raising of the saints, who made their way about Jerusalem. This reconstruction might fit 1 Corinthians, if it was possible to interpret the firstfruits of 1 Corinthians 15 with multiple events.

However, a careful reading of the text shows that this simply is not true. In the Matthew passage quoted above, in the Christian Standard Bible translation, Jesus dies upon the cross on Good Friday (v. 50), then followed by the phrase, “Suddenly….” in verse 51, describing all of the events associated with the death of Jesus, which includes the opening of the tombs and the raising of the saints, all happening there on Good Friday (see verses 51 and 52). It is not until Sunday, after Jesus’ Resurrection do these saints leave their tombs and appear about the city, as we find in verse 53.

What the raised saints were doing in their tombs over the weekend is anyone’s guess…. perhaps they were waking up from their long sleep?? But the point here is to say that the raising of these saints preceded Christ’s Resurrection, which if understood in a non-metaphorical manner, would contradict with what Paul says in 1 Corinthians 15. That is a serious problem.

The “Suddenly…” of the Christian Standard Bible (CSB) in verse 51 is obscured in the otherwise excellent English Standard Version (ESV), which has the more archaic “Behold...” The New International Version (NIV) renders this as “At that moment…” There really is no way that you can delay the raising of the saints, in their tombs, until two days later, if the traditional historical interpretation is to be adopted.

However, the most pressing concern is the theological meaning behind the whole “zombie” episode. For if the point of the episode is to tell us that a number of saints were resurrected before Jesus’ Resurrection, it really messes with the whole theology of Resurrection that Paul is trying to describe in 1 Corinthians 15.

Unlike the “resurrection” of Lazarus, who eventually did die sometime in the 1st century timeframe, the Resurrection of Jesus is quite different. When Jesus died on the cross, and then was Resurrected, this Resurrection was (and “is”) permanent. In other words, Jesus will never die again. Likewise, the hope that Paul is trying to give to the Corinthian church is that Resurrection for us as believers, is unlike the story of Lazarus. Instead, our Resurrection will be like that of Christ’s Resurrection. For those believers who have died prior to Jesus’ Second Coming, they will be raised to eternal life, and they will never die again, following the example, the firstfruits, set by Jesus himself.

If this is indeed the point of the Matthew story, then we really are not dealing with something out of a “zombie” horror movie. Rather, the raising of the saints is a look into the future, whereby Matthew wants to reassure the reader that the coming Resurrection of Jesus two days later, after the Crucifixion, is the same hope that we can have as believers, that in the “End Times,” all who have died in Christ will be raised in Christ…. permanently!!

For the Christian, Jesus has conquered death, permanently. That is Good News!!

This is why the “special effects” apolocalyptic literary device mentioned by Michael Licona makes sense with the metaphorical interpretation, in contrast with the traditional, historical interpretation of this passage in Matthew’s Gospel. Historical critical analysis of this particular text chimes in well with the generally accepted view today that the Gospels fit within the literary genre of Greco-Roman biography. For example, Virgil describes the death of Julius Caesar with all sorts of reports of various apocalyptic phenomena, such as cattle speaking, streams standing still, pale phantoms being spotted at dusk, the opening up of the earth, and a comet being seen. It would have been perfectly acceptable for Matthew to use a similar literary device to make a theological point about the believer’s hope in a future Resurrection.

Where Do You Land on Understanding the “Zombie” Passage in Matthew’s Gospel?

So, which is the better interpretation of this passage? Is it the traditional, historical view, or the metaphorical, future-looking ahead view? Scholars will weigh the evidence differently, in order to make a judgment on the probability of an event. This is not a hill that I am willing to die on, but in my mind, the evidence favors the metaphorical view as the better interpretation, when examining all of the evidence. Has the burden of proof been met, to overturn the traditional view? I would say, yes, but many other devoted Christians would probably disagree with me here.

What does bother me is when some advocates of the traditional, historical view regard advocates of the apocalyptic/metaphorical view as somehow having a lower view of the Bible. With all due respect to such critics, the idea of promoting a particular “miraculous” interpretation of a difficult passage that results in postulating a contradiction in the Bible is not a good way of trying to supposedly “defend the Bible.”

Nevertheless, what both the traditional, historical view and the apocalyptic/metaphorical view have in common is the affirmation that God has the power to conquer death, and that God has done this through the Resurrection of Jesus. That message should give us hope that death does not have the final word. When all seems bleak, and at its darkest, we can trust in the reality that “Sunday is a’coming.”

In these early years of the third decade of the 21st century, we have endured the stench of death from the loss of friends and family who have suffered from Covid-19, and now more recently, we recoil from the horror of bodies left piled up on the streets of the cities of Ukraine. Thankfully, the story of the Christian faith gives us a sense of hope that a Resurrection awaits those who put their trust in Jesus, no matter how dark our world seems today. That is a message worth pondering on Good Friday.

In the next post of this series on “historical criticism,” I will review a book written by one of the finest conservative Bible scholars alive today, that uses the tools of “historical criticism” in a very responsible manner, without falling off any theological cliffs, as so many other advocates of “historical criticism” have repeatedly done. Look for it in a week or so.