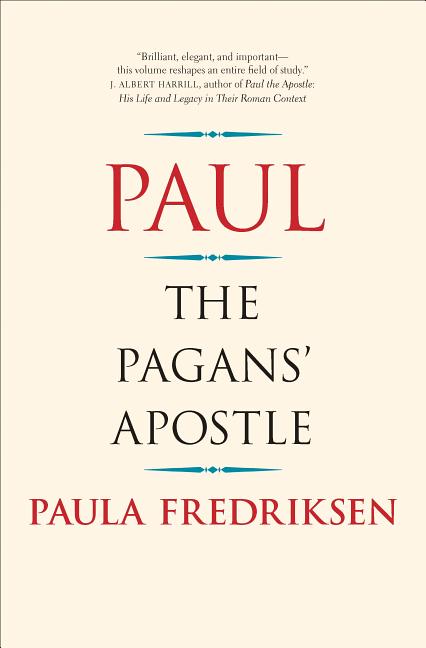

When Paul became a Christian, did he cease to be Jewish? What prompted the thinking behind Paul’s Gospel, which sought to include Gentiles among the people of God through having faith in Christ signaled by baptism, and not through circumcision? Such are some of the questions that Paula Fredriksen seeks to answer in her Paul, the Pagans’ Apostle.

(Time for another Bible-nerdy book review…..this book is very rich, but can be very dense, for the average reader)

Paula Fredriksen is one of the most recognized and highly respected scholars of early Christianity today. It took me two years, but I thoroughly enjoyed her monumental study Augustine and the Jews: A Christian Defense of Jews and Judaism, and reviewed it here on Veracity several years ago. She knows her field incredibly well. Until 2009 she researched and taught at Boston University and has since served at Hebrew University in Jerusalem. She hit the media spotlight in 1998 when she acted as the primary consultant for the PBS Frontline program, From Jesus to Christ: The First Christians, which was one of the first mainstream television programs to bring the so-called “third” quest for the historical Jesus, active in academic circles, to the eyes and ears of a popular American audience.

Early Christian historian Paula Fredriksen, though not a professing Christian, argues in her Paul: The Pagans’ Apostle that Paul did not “convert” to Christianity. Rather, Paul saw Christianity as fulfilling the message of the Hebrew Scriptures, and that Paul remained within the fold of Judaism to the very end of his ministry.

A Scholarly, Non-Evangelical Look at the Life & Ministry of the Apostle Paul

For Veracity readers, it is important to know that Dr. Fredriksen is not an evangelical in her theological orientation. From Jesus to Christ: The First Christians alarmed conservative Christians in the promotion of “Jesus Seminar” views that were well publicized in the 1990s. But in fairness to Dr. Fredriksen, she does not come across as having an axe to grind, as it is not completely clear to me even what her theological convictions are, though I have been told she is a former Roman Catholic turned Jewish. According to her writings, she seeks to act purely as an historian, putting together what she estimates is a competent reconstruction of the historical record, even where our current sources are not as plentiful as we would all like. Though popular among skeptics, Paula Fredriksen does not appear to be cynically antagonistic, for she acknowledges a set of facts, an “historical bedrock,” that does not explicitly rule out the central Christian claim that Jesus bodily rose from the dead.

To say that Dr. Fredriksen is not an “evangelical” is also to acknowledge that she does not uphold an historically orthodox, Christian view of the New Testament and its inspiration. Instead, she follows the thinking common in secular academia today regarding how the New Testament documents can be viewed as historical sources for reconstructing the life of Jesus and the period of the earliest Christ followers. This would include the topic of Paul, the Pagans’ Apostle, the life of the Apostle Paul. Outside of academia, and certain social media circles, few evangelical Christians know how a certain breed of scholars have a view of the Bible so radically different from their own.

For example, whereas the letters of Paul can be trusted upon as historically reliable, the Book of Acts is only reliable up to a certain point in comparison (Fredriksen,see footnote 1, chapter 3. ). She furthermore dates the writing of the Book of Acts to the early second century, which effectively takes the traditional authorship out of the hands of the historical Luke, who probably died long before the first century ended. She concludes this, despite the fact that the well known British 20th century liberal scholar, John A.T. Robinson, saw no firmly established scholarly reason why the entire New Testament could not be dated before the year 70 C.E.

But even with the “letters of Paul,” a caution is in order, in that of the thirteen letters directly ascribed in the New Testament as being written by Paul, only seven of them are considered to be authentic, whereas the letters 2 Thessalonians, Ephesians, Colossians, 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus are to be regarded as letters written after Paul’s death, by writers other than Paul, seeking to modify Paul’s theological agenda. None of this would sound strange at all to an atheistic scholar, like a Bart Ehrman, who fully embraces such views.

For those committed to the idea that our received New Testament canon is the final authority for Christian faith and practice (as I do), such views held by academics like Dr. Fredriksen (and Dr. Ehrman) are in direct conflict with an evangelical view of Scripture. As will become evident in this review, a number of conclusions that Dr. Fredriksen makes about early Christianity will stand at odds with more classic understandings of Christian belief. Nevertheless, while I disagree with Dr. Paula Fredriksen regarding her view of the Bible, I still think that historically orthodox Christians can learn a good deal from her, particular from someone as skilled and learned as she is.

As a Christian, Did Paul Remain a Jew?

With this caveat in mind, there is much to be gained from Paula Fredriksen’s central thesis that Paul remained a Jew, and continued to be thoroughly Jewish, as he became perhaps the single most articulate and influential leader of the early Christian movement, after the crucifixion, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus. The question that continues to puzzle such scholars is in explaining how such a committed Jew like Paul came to the conclusion that a way be opened up to include Gentiles among the people of God, along with Israel, without the circumcision requirement that classically identified what it meant to a member of God’s covenant people.

For many Christians today, knowing that Paul has a Jewish background is a “no-brainer.” I mean, is it not obvious? Paul was Pharisee, was he not? However, Dr. Fredriksen argues in Paul, the Pagans’ Apostle that the importance of Judaism in the life of Paul, after he became a follower of Jesus, and as apostle to the Gentiles, has been greatly misunderstood and under appreciated.

Part of the key in appreciating Paula Fredriksen’s approach comes in perceiving the difference between “Gentiles” (a religiously neutral, ethnic term) and “pagans” (a religiously specific, ethnic term denoting non-Jews and non-Christians). For a non-Jew to follow Jesus, in Paul’s mind, they would remain a Gentile but they would need to give up their pagan idolatry and beliefs.The question of what is a “Gentile” and what is a “pagan” has interested me for years, and Paula Fredriksen thoroughly explores the topic.

Since the 1977 publication of (the late) E.P. Sanders Paul and Palestinian Judaism, a revolution has taken place in the academic study of Paul. Since the days of Martin Luther, in the 16th century, much of Protestant scholarship has insisted on a radical break between the Christian message of Paul and the story of Judaism. But with the advent of this “New Perspective on Paul,” inaugurated by Sanders’ research, a one-time professor at the College of William and Mary, where I currently work on staff, scholars have been working to reassess Paul’s relationship to the Judaism of the first century. Some look upon the “New Perspective on Paul” as a refreshing way of trying to approach the intractable divide between Protestants and Roman Catholics on the thorny issue of justification, whereas others view it as a threat to undermining the classic Reformation view of salvation.

Paula Fredriksen’s Paul, the Pagans’ Apostle attempts to steer a middle course through the debate between the New and Old Perspectives of Paul, which is probably the most sensible path forward. Fredriksen’s research is top notch, as her endnotes are well documented, something that the audiobook version I listened to on Audible sorely lacked, which meant a trip to the library for me! Fredriksen’s description of the Greco-Roman and Jewish worlds that Paul lived in is very insightful, and gives the reader a lot of food for thought. Still, there are other assumptions made in Fredriksen’s work that will frustrate evangelicals who try to read her.

Did the Council of Nicea Get Paul Wrong?

A modest acceptance of at least some of the New Perspective on Paul has even made its way into conservative evangelical circles, notably through the writings of N.T. Wright, perhaps the most well known New Testament scholar living in our day, in the first quarter of the 21st century. Nevertheless, Fredriksen’s approach is colored by a sharp disagreement she has with scholars like Wright, mainly in what undergirded the sense of urgency that Paul had in trying to spread his Gospel far and wide throughout the Roman Empire.

In a stunning statement, most likely directed at scholars like Wright, Paula Fredriksen urges “that we try to interpret both Paul and his Christology in innocence of the imperial church’s later creedal formulas.” This would suggest that Dr. Fredriksen believes that the early church’s move to articulate in the Nicene Creed an affirmation of the Son as being of the same substance as the Father is actually a distortion of the Gospel message being promoted by the historical Paul, as she sees him. Really?

Her analysis comes partly from her reading of Philippians 2:5-11:

Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. And being found in human form, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross. Therefore God has highly exalted him and bestowed on him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father (ESV).

Fredriksen notes that our English translations can fool us here, in that the word “God,” capitalized four times in this passage, commonly suggests the one divine being, God the Father. However, in the first two instances (verse 6) the word “God” has no definite article whereas later (verse 9), beginning with “Therefore God,” does have the definite article in the original Greek. In her view, this suggests that the reference to “therefore (the) God” means that it was God the Father who highly exalted Jesus, but those two prior references, which she translates in lower-case merely as “god,” or “a god,” as in “in the form of a god,” is a reference to divine status, but that this divine status is for some other divine being apart from God the Father. “Paul distinguishes between degrees of divinity here. Jesus is not ‘God’” (Fredriksen, p. 138).

I can only imagine Arius, the arch-heretic who debated the other early church fathers gathered at the Council of Nicea, issuing to Dr. Fredriksen a hearty “thank you!,” as Arius believed that Jesus was divine, but not in the same way the Father was divine. Jehovah’s Witnesses today pick up the same type of idea by asserting that Jesus was an angel, a divine being, but surely not of the same substance as God the Father, which was articulated in the creed at Nicea. For Fredriksen, Arius was simply reading his Greek New Testament to make his case against anything that hinted of a Triune nature of God, in an effort to uphold what he understood to be monotheism.

Dr. Fredriksen then goes onto handling an objection, namely that for Paul to say that “Jesus Christ is Lord,” according to the ordinary Greek of the day, suggests that the meaning of “Lord” (kurios, in the Greek) is a deference to any social superior, and not necessarily divine (Fredriksen, p. 139). However, a careful examination of the passage that Paul is drawing from in the Septuagint (LXX) indicates otherwise. Throughout Isaiah 45, from where Paul gets his “every knee shall bow” and “every tongue confess” (Isaiah 45:23), each reference to the one true God is that Greek word for “Lord;” that is, kurios. This would indicate that Paul undoubtedly had Jesus’ associated with the one true God in mind, and not merely some lesser divine being.

In other words, while Arius might have had certain good intentions of protecting against some form of polytheism in his reading of Paul, the orthodox church fathers who eventually won the debate at the Council of Nicea were able to read Paul better in his Old Testament context, thus making the case for Trinitarianism, against Arius. Dr. Fredriksen would strongly disagree with my assertion here. Nevertheless, historically orthodox Christian believers have understood Paul this way ever since. The Nicene Creed remains one of most familiar and well-affirmed statements of Christian belief in the history of the Christian movement, a common statement of faith among Protestants, Roman Catholics, and Eastern Orthodox alike.

A Common Assumption in Academia: Paul Emphatically Expected the Return of Jesus Within His Lifetime

So, given the shortcomings in her argument, why does Dr. Fredriksen urge such a movement away from the conclusions drawn up at the Council of Nicea? Dr. Fredriksen follows the standard consensus view among notably critical New Testament scholars, such as Bart Ehrman, that Paul “lived and worked in history’s final hour” (Fredriksen, p. xi), a well-known thesis popularized by the influential German New Testament scholar of the early 20th century, Albert Schweitzer. In other words, Paul was absolutely convinced that Jesus would return as the victorious Jewish Messiah, to set the world order aright, sometime during his lifetime. This apocalyptic, eschatological expectation of the Apostle Paul is what drove him to preach far and wide across the greater Mediterranean coastlines and even inland.

As this story goes, when Paul eventually died, probably in the 60’s C.E., and there was no returning Messiah in sight, the Christian church was put into an existential crisis. What we possess in our New Testament today is essentially a combination of those early writings by Paul, along with other writings that came later, like the Gospels, that seek to refashion the message of the early Christian movement. With the failure of Jesus’ imminent return, this modified Christian movement, ultimately defined and regulated by the early church councils, most notably the Council of Nicea, now must endure for the “long haul,” something which has continued to survive and thrive now for 2,000 years.

Pushing Back Against the “Ghost of Albert Schweitzer”

In his multipart review of Paul, the Pagans’ Apostle, evangelical New Testament scholar Ben Witherington, of Asbury Seminary, critiques this presuppositional mindset that scholars like Dr. Fredriksen possesses. Witherington acknowledges that Fredriksen presents her central thesis well, despite the inadequacies of the Ehrman/Schweitzer approach that Fredriksen front loads to her book.

For example, when Paul states in Romans 16:20 that Christ will “soon” crush Satan under the feet of the Roman Christian community, he means that the crushing of Satan will happen “quickly,” a statement about how Satan will be crushed and not exactly when this would happen. For Paul also reminds the Romans in chapter 15 that he must go to Jerusalem, then to Rome, and then hopefully to Spain. So it would be odd for Paul to tell the Romans of his planned future schedule, years out in advance, while simultaneously announcing the coming end of the world, as he knew it, at any moment, as he was writing this letter. After all, Jesus himself acknowledged that he did not know the exact timing of his Second Coming (Mark 13:32). Witherington remarks, “Could we please now let the ghost of Albert Schweitzer rest in peace, and stop allowing his misreading of Paul to continue to haunt the way we evaluate Paul?”

Nevertheless, even Witherington largely agrees that Dr. Fredriksen is correct to say that Paul was not a “convert” to Christianity, in the sense that Paul was somehow leaving his Judaism behind to become a Christian. Instead, Paul saw that the Gentiles’ acceptance of the Gospel was part of the new post-Resurrection-of-Christ reality, that had been a part of Israel’s story told for centuries within the Old Testament. In other words, for Witherington, Paul’s “conversion” was an expression of his Jewishness, in light of the coming of the Messiah, albeit a rather radical expression, more radical than what Fredriksen is willing to admit.

Many Christians for centuries have imagined Paul to have “converted away” from Judaism, when he became a follower of Jesus, whereas Fredriksen is an advocate of the “Paul Within Judaism” school of thought. Sadly, this “parting of the ways” between Judaism and Christianity was exacerbated by the severe drop off of Jews entering the Christian movement, and rapid increase of Gentiles joining the movement, particularly after the failure of the Bar Kokhba revolt in the early 130’s C.E.

That being said, Witherington faults Fredriksen for being too dismissive of some of the historical details that Acts offers up to support the narrative found in Paul’s letters about his own life, or to miss the more radical implications of Paul’s message, even in his own letters. For Paul saw that the death and resurrection of Jesus inaugurated a New Covenant, a fulfillment of what Jeremiah 31 says would be the law written on people’s hearts. Yes, Paul remained a Jew throughout his life, but following his road to Damascus experience, he radically reframed his Judaism along the lines that would eventually inform historical, orthodox Christianity (The late New Testament scholar Larry Hurtado shares a similar appreciation of Fredriksen’s approach while offering critiques similar to Witherington’s).

Paul in prison, by Rembrandt (credit: Wikipedia)

True Judaism for the Apostle Paul

With those critiques already in view, it is helpful to consider positively more what Paula Fredriksen is trying to do in her central thesis regarding Paul. The challenge of properly translating a passage like Galatians 1:13-14, when Paul explains his former life before becoming a follower of Jesus, is a case in point:

For you have heard of my former life in Judaism, how I persecuted the church of God violently and tried to destroy it. And I was advancing in Judaism beyond many of my own age among my people, so extremely zealous was I for the traditions of my fathers (ESV).

What does Paul mean by “Judaism” here? Is he implying that by becoming a follower of Jesus that he is leaving one religion to join another? No, says Fredriksen. But if not, what then does Paul mean?

Furthermore, what is one to make of Romans 2:1-29, where Paul suggests that “true circumcision” is a matter of the heart (particularly Romans 2:29)? Being a “true Jew” is a matter of the spirit, of having the law inside of you, and not in one’s flesh. Is Paul redefining Judaism by taking circumcision out of the mix? Or is Paul addressing Gentile Christians here, showing them that circumcision should not be a barrier to their following Jesus?

There were certainly barriers for Gentiles to become Jews in the first century. The “God fearers” of the New Testament were attracted to the message of Judaism, but would not follow with circumcision. You also have the question as to how much proselytizing of Gentiles by traditional (non-Christian) Jews was actively being done in the first century, a practice that Dr. Fredriksen is skeptical about.

Who exactly were the Judaizers that Paul opposed in Galatia, those supposed followers of Christ who opposed Paul’s anti-circumcision efforts among the Gentiles? Did they really come from James’ church in Jerusalem? Were they instead other supposed Christ-followers, unaffiliated with James, who opposed Paul’s missionary tactics as being compromising? Was the conflict in Galatia over the same issue Paul faced in Antioch, or something different? Was the specific Judaizing complaint table fellowship between Gentile and Jewish believers in Jesus, or something else?

Paul vs. Judaism, or Paul vs. Christian Judaizers?

These are the questions that preoccupy Paul, the Pagans’ Apostle. One point that Fredriksen raises deserves highlighting. In Galatians, particularly in Galatians 4, where Paul brings out an allegory comparing the children of Sarah versus the children of Hagar, Fredriksen notes that most interpreters historically have said that Paul is comparing Christianity (children of Sarah) with Judaism (children of Hagar). But Fredriksen claims that this interpretation is incorrect, in that Paul is arguing for the difference between Christ-followers who take his approach to Gentile evangelism (children of Sarah), and those other Christ-following Jews who oppose him, and distort the Gospel (children of Hagar). On this observation, I find Paula Fredriksen’s argument quite persuasive (Fredriksen, p. 99-100).

Scholars, both conservative and liberal, have acknowledged that the preaching ministry of Jesus, prior to the crucifixion, was oriented towards the Jews of Palestine. Jesus rarely ventured outside of Jewish-dominated areas in what we now call the land of Israel. With a handful of exceptions, Jesus’ primary audience was Jewish.

It was not until Paul came along, with his road to Damascus experience with the Risen Jesus, that the early Christian movement began to actively engage outreach among the Gentiles. By emphasizing having faith in Christ, and removing circumcision as the traditional barrier for entry among the people of God, as described in the story of the Bible, Paul revolutionized the Christian movement. At the same time, Dr. Fredriksen argues, the Apostle Paul himself, along with the original members of Jesus’ apostolic circle, remained committed to their own ancient Jewish customs, despite the trend in later Christianity to make Paul appear to be anti-Jewish (Fredriksen, p. 106).

For while Paul vehemently opposed the “Judaizers” who distorted his Gospel in Galatia, Paul still insisted on at least some form of “Judaizing” for Gentile followers of Jesus. He insisted that Gentile believers forsake idolatry, adhere to the Ten Commandments, give up sexual immorality, and uphold “any other commandment” of the Law (Romans 13:9, Fredriksen, p. 119). This raises the question as to why Paul drew the line at circumcision as he did.

Rethinking Old Approaches to Paul

Dr. Fredriksen wades into the debate over the meaning of “faith” (pistis, in Greek), which she sees as having a long history of referring to “psychological inner states concerning authenticity or sincerity or intensity of ‘belief‘.” She corrects this misunderstanding by appealing to a meaning more sensible to Paul’s first century context, that of ‘“steadfastness” or “conviction” or “loyalty”‘(Fredriksen, p. 121). I resonate with her translation of Romans 13:11b: “Salvation is nearer to us now than it was when we first became convinced.” Compare this with the Common English Bible translation of the same: “Now our salvation is nearer than when we first had faith,” which is much more ambiguous.

From a fresh perspective, Dr. Fredriksen contends that the mysterious “I” of Romans 7:7-22 is a rhetorical device used by Paul, and not a reference to his own spiritual struggles, neither as a non-believer before his encounter with Christ, nor himself as a believer (example v. 15: “For I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate“). Accordingly, Paul is self-identifying as “the non-Jew who struggles to live according to Jewish ancestral customs,” as they follow Christ (Fredriksen, p.123-124). This reading is quite plausible, though it is quite different from the late-Augustine interpretation of Paul’s struggle with indwelling sin as a believing Christian. Nevertheless, both Fredriksen’s reading and the late-Augustinian reading are not necessarily in conflict with one another.

Fredriksen is convinced that Paul knew his Hebrew Scriptures (the Old Testament) well enough to know that there would come a day when the nations of the world would turn from their idolatry and embrace of the God of Israel. With the coming of Jesus as the Messiah, Paul knew that this day had come. But this bringing in of the Gentiles into God’s covenant people would not be limited by circumcision, but rather would be conditioned by their response of having faith in Jesus. Paul sees this as being completely consistent with the message of the Hebrew Scriptures, and is therefore adamantly opposed to other Jewish “Christ-followers” who do not read the Old Testament just as he has.

Furthermore, there is no such thing as two different ways of salvation, one for the Jews and another way for the Gentiles. All of the people of God, whether they be Jew or Gentile, are reconciled to God through faith in Christ.

The way Dr. Fredriksen frames her argument has implications on how Christians should read their Bible. For example, many Christians continue to read the Book of Romans without this Pauline mindset in view. As a result, many Christians look at his whole argument for justification/salvation as starting in Romans 1 and culminating in Romans 8, with Romans 12-16 as being about the application of Paul’s theological treatise. Romans 9-11 then sticks out like a sore thumb, as like some sort of appendix bolted onto Paul’s teaching in Romans 1-8. Yes, Romans 8 does end with a glorious promise that no one will separate us from the love of Christ. But there is more to the story. The lesson I take from Dr. Fredriksen is that the Romans 1-8 story only gets us part of the way there to where Paul is going. Rather, Paul wants to show us how “all Israel will be saved” (Romans 11:26). Paul’s theological argument runs from Romans 1-11, where Romans 8 offers a theological crescendo, but Romans 11 is the real climatic conclusion.

As an aside, on a somewhat minor point, Paula Fredriksen is completely right to say that Paul’s allusion to Isaiah 45:23, that “every knee shall bow” to God, in both Philippians 2:10 and Romans 14:11 is about all of the nations coming to the conscious realization that Jesus is the True Messiah, not simply that of Israel, but that of all of the nations of the world, at his final return (footnote 15, chapter on “Christ and the Kingdom”). These New Testament verses have been used either to justify some type of begrudging acceptance of Jesus’ Lordship by the wicked in hell, after the final judgment, or to justify a type of Christian Universalism, implying that every human individual will be saved in the end. However, the reference to “every knee shall bow” by Paul is not about individuals but rather about the nations, with every bowing of the knee referring to each distinct national allegiance, as the context of Isaiah 45 shows.

Rethinking Pauline “Anti-Jewishness” …. (Without Compromising Historically Orthodox Christianity)

Nevertheless, a number of other conclusions made by Dr. Fredriksen are driven by her acceptance of the common academic narrative that the authentic Paul only wrote seven of the thirteen letters we possess, which is further skewed by her adoption of the Ehrman/Schweitzer “imminent end of the world” thesis. In fact, these are fundamental assumptions that she makes without apology (Fredriksen, p. 252).

This is quite evident when you compare Fredriksen’s reading of 1 Thessalonians, an undisputed letter of Paul, which includes the famous passage on the “Rapture” (1 Thessalonians 4:13-18), which she believes teaches the imminent return of Christ within Paul’s lifetime, with her reading of the disputed 2 Thessalonians, which she believes was written by another author claiming to be Paul, which “explained the reasons for the Kingdom’s evident delay, adding a punch-list of necessary further events before the final apocalyptic scenario could unwind (2 Thes. 2:1-11)” (p.169). In other words, in her view, 2 Thessalonians attempts to fix Paul’s erroneous expectation, sometime after Paul’s death of the coming Kingdom with a different message, that emphasizes a more “we-are-in-this-for-the-long-haul” approach to the consummation of world history.

As another example, she appears to favor the position that the “deutero-Pauline author [of Ephesians] collapses the ethnic distinctions that Paul himself upheld” (footnote 35, chapter on “Paul and the Law”) between Jew and Gentile, in contrast with the authentic Paul. Furthermore, she believes that the authentic Paul discouraged the act of having children, as being a distraction from the imminent return of the Messiah (p. 113). She believes that the “Pauline” teaching about parents having authority over their children, as described in Ephesians and Colossians, was a non-Pauline teaching introduced into our New Testament to accommodate the reality of the failure of Jesus to return within Paul’s own lifetime.

Paula Fredriksen asks vital questions about Paul’s precise thinking about the message of the Gospel with his self-understanding of what it meant to be Jewish. Fredriksen rightly reveals the theological wedge driven between Paul the missionary to the Gentiles and Paul the faithful Jew, a trend that eventually dominated a great deal of Christian theology. While the phrase “replacement theology” is often too elusive here, it is correct to say that if there was one particular failure of the early church, particularly from Constantine onwards, it was the tendency to marginalize the Jewishness of the earliest Christian movement to the point of enabling a kind of anti-Judaism that has done tremendous harm throughout Christian history.

While voices like Origen and Augustine resisted such anti-Jewish thinking, by reminding their readers that Paul and other early Jewish Christian leaders maintained many of their ancient Jewish customs, not everyone heeded these voices. This anti-Judaism wedge was even codified into certain aspects of Roman law, in the post-Constantine era (Fredriksen,see footnotes 25, 26, under chapter “Paul and the Law”). Aside from Origen and Jerome, very few of the early church fathers even understood Hebrew, which is the primary language in which the Old Testament was written in!!

But Paula Fredriksen’s attempt to obliterate that wedge is eventually an overcompensation, a product of her historical methodology. For it is evident that her view of the New Testament contrasts sharply with the received view of the church, down through the centuries, which views all of the thirteen letters of Paul as being authentically Pauline. I, on the other hand, believe that the early church got the canon of Scripture right!

Anti-Judaism is not a core feature of historical, orthodox Christianity. For example, you would be hard-pressed to find conservative evangelicals who do not possess profound sympathies with Jewish people today. In other words, you do not have to buy into the full revisionist program of much of critical scholarship today in order to root out “anti-Jewishness” understandings of Paul that have, nevertheless, crept into at least certain interpretations of the New Testament.

There are plenty of resources within historical, orthodox Christianity to tackle the task Paula Fredriksen takes up. She convincingly demonstrates that a traditional view of a Paul who “converted” from Judaism to Christianity is anachronistic and wholly unnecessary. For the language of “conversion” presupposes a modern concept of “religion” which was in many ways foreign to Paul and his world. Paul’s Christianity was not a rejection of Judaism, per se, but rather it was the outworking of his Jewish faith, set within the context of the coming of the Messiah.

In other words, while is it surely correct to say that Paul indeed “converted” to Christ, by embracing Jesus’ mission and following the Risen Lord, it would be wrong to say that Paul “converted” away from Judaism to get to something else, like “Christianity.” As an evangelical, I am thankful to Dr. Fredriksen for pointing this out. However, it is not a prerequisite to accept the whole of Fredriksen’s critical, non-evangelical assumptions about the Bible to get her central thesis.

Rethinking Paul’s Greatest Letter: To the Romans

However, I am not entirely convinced yet by Dr. Fredriksen’s attempt to re-read Romans is correct, though it is a coherent and plausible reading. She believes that Paul’s audience are Gentile Christians, at least some of whom consider themselves as “Jews” (Romans 2:17). Yet she does not think that Paul is addressing any actual Jewish, bodily-circumcised Christians in Romans. Instead, Pauls uses a rhetorical style, by implicitly addressing a “so-called Jew” as the interlocutor of his argument; that is, a Gentile Christian who is trying to Judaize too much (Fredriksen, pp. 156ff). This goes against the standard reading that the recipients of Paul’s letter to the Romans were a mix of both Gentile AND Jewish Christians, who were not necessarily getting along very well with one another, from the reports Paul had received. So in Romans 2, according to Fredriksen, Paul is addressing a Gentile “who calls himself a Jew,” and not someone who was bodily circumcised, a view consistent with how she interprets Romans 7 (see above).

The problems here are several. First, it is hard to imagine that Paul would go to such great lengths to write such a treatise to a Christian community he had not yet met, and completely ignore the Jewish part of that community in his correspondence. When Phoebe presented Paul’s letter to the church in Rome (Romans 16:1-2), did she ask the Jewish Christians to leave the room while inviting the Gentile Christians to stay and listen? Probably not. But perhaps the believers in Rome, both Jew and Gentile, would have caught onto Paul’s rhetorical style. But then, maybe not.

Secondly, according to Dr. Fredriksen, Paul’s great statements in Romans about justification, particularly in Romans 3, are primarily aimed at Gentile believers, and not all believers as a whole. This does not necessarily mean that Paul’s teaching about justification could not be extended to Jewish Christians as well, as a further application of Paul’s teaching in Romans. But I am not yet persuaded that her reading of Romans will bring about a clear breakthrough in the persistent debates regarding the nature of justification among theologians. Excluding Rome’s Jewish Christians from the intended audience of Paul’s letter to the Romans is a problematic weakness to Dr. Fredriksen’s argument.

I might add that there are a few other places in Paul, the Pagans’ Apostle, where it is hard to connect Dr. Fredriksen’s conclusions with the actual data she cites. For example, in her discussion about the controversial term “righteousness“, (in Greek, dikaiosynē) she ties Paul’s thinking of righteousness quite exclusively to the adherence to the second table of the Ten Commandments, which does not exactly line up with the Scriptural texts she references (Fredriksen, p. 120-121).

In the prior paragraph, she rebukes the RSV translators for rendering Romans 1:4b-5 as “Jesus Christ, through whom we have received grace and apostleship to bring about obedience to the faith,” as there is no definite article associated with “faith” in the Greek original. Fredriksen is correct in that the use of “the faith” connotes the idea of faith as a set of propositional statements that one must believe, which is not in view here in Paul’s writings. But the version Fredriksen is quoting dates back to the 1953 printing of the RSV, a reading that was apparently grandfathered in from the KJV. Yet as of 1973, the inclusion of “the” in “the faith” had been removed from the RSV, and I could find no modern, recent translation of the RSV, the ESV that succeeded it, nor the new NRSV with the definite article included. Perhaps Dr. Fredriksen mistakenly had the KJV in mind, but it would seem odd to point out an error in the RSV that was corrected perhaps some 50 years ago. Little head scratchers like these pop up every now and then in Paul, the Pagans’ Apostle.

With all of this in mind, I would not necessarily recommend Paul, the Pagan’s Apostle to Christians who are unfamiliar with Fredriksen’s type of critical biblical scholarship. The landmines you would have to walk over to get to the valuable insights Dr. Fredriksen has regarding a neglected aspect about Paul and his mission might be too distracting and discouraging. But for someone who can read something like a Bart Ehrman book, without throwing it at the wall in utter frustration, Paula Fredriksen’s Paul, the Pagan’s Apostle makes for a provocative and refreshing look at the Apostle Paul.

Rethinking Paul? So What??

Some might respond with a yawn about such questions that come up about Paul and his relationship to Judaism, with a “So what?” But such indifference is woefully mistaken.

The circumcision issue in Paul’s day is not something which has no bearing for Christians today. A lot of people wonder if certain other “quirks” of Judaism still apply for Christians in the 21st century. Some argue that Paul’s dismissal of the circumcision requirement for Gentiles, in order to be Christian, is a model for jettisoning other peculiarities associated with the Old Testament-inspired Jewish tradition for us living 2,000 years later. Others (like myself) disagree, saying that Paul’s “disputable matters” position on eating food sacrificed to idols and his opposition to Gentile circumcision for Christ-followers was more probably unique for those particular issues Paul was thinking about and should not be confused with contemporary concerns, such as with Westernized rethinking concerning gender, sexuality, and marriage, explosive topics for not only non-believers but believers in Jesus today as well.

There were “God-fearers” in the first century Roman Empire, such as the centurion in Luke 7:1-10, who admired the Jews and who were drawn to the God of Israel, and yet they were not prepared to go the full conversion route into Judaism by becoming circumcised. Perhaps there are “God-fearers” today (or some nearly equivalent category) who admire the Christian faith, but who find certain obstacles to historic orthodox Christian belief and practice that they are unwilling to embrace. This is an area that requires concentrated thought and discussion, in our current post-Christian era where once widely accepted Christian beliefs and practices have now become deeply controversial in recent decades.

Then there is the whole debate about justification, that placed an intractable wedge between Protestants and Roman Catholics in the 16th century, that still haunts the church to this day. The type of reassessment of the Apostle Paul offered by scholars like Paula Fredriksen might go a long way towards opening new paths for dialogue in healing this rift within the Christian movement. I read her Paul, the Pagans’ Apostle, as a prelude to her more popular and accessible work, When Christians Were Jews, which I hope to get to in due time.