Joseph and pregnant Mary at the census. But what if we got this picture wrong, and Joseph and Mary went to Bethlehem for the census, when Jesus was 10 years old? (credit: Chora Church, Istanbul/Shutterstock)

If this proposal turns out to be correct, it would positively throw perhaps the best argument AGAINST the historical reliability of the Bible into the dumpster…. But to get the idea, you would have to completely rethink how Luke handles chronology. Veracity readers, get out your thinking caps!

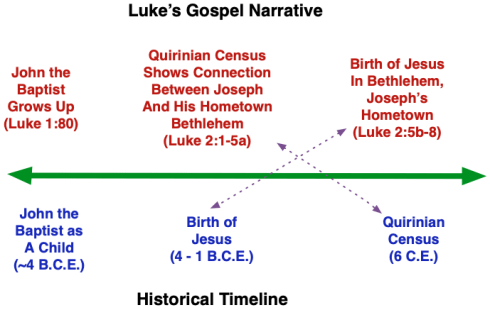

One of the thorniest apologetic challenges is trying to fit Luke’s traditional dating for Jesus’ birth to Caesar’s census, during the time when Quirinius was governor, with Matthew’s version, which has Jesus born during the latter years of Herod. The big problem is the timing. Luke’s Quirinian census is typically dated to 6 A.D., largely due to Josephus’ historical record, whereas Matthew’s description of the death of Herod is somewhere around 4-1 B.C.

That is like at least a 7-10 year discrepancy. Whoops.

Skeptics of the Bible often point to this as proof that the Bible has errors in it, and therefore, the Bible can not be trusted for history.

Over the years, Christian apologists have put forward various explanations to account for this discrepancy. Perhaps we are talking about a different census, with Luke’s census happening a few years earlier, but that we simply have no secular or other record for it. Perhaps Josephus was wrong on his dating of events. While these proposals present some thoughtful possibilities, the critics often respond with, “Meh…. There go the Christians again, overreaching for an apologetic.”

But what if the traditional reading of Luke’s story has been misinterpreted? What if it is possible, that about 10 years after Jesus’ birth, after living a few years in Nazareth, the Holy Family returned back to Bethlehem for the census? What if the story about the census is a digression, purposefully inserted by Luke, temporarily jumping ahead in the chronological narrative, before returning back to the main story about Jesus’ birth?

Sure, this rearranged chronology might mess with the familiar nativity scenes, most churches show on Christmas, but it actually might make better sense of the data we have available, both within the Scriptures and outside of the Scriptures.

I argue for a similar literary technique used by Luke in Acts, regarding the number of visits Paul makes to Jerusalem, that attempts to reconcile with Paul’s own story in Galatians. Studies by New Testament scholars, such as Michael Licona, author of Why Are There Differences in the Gospels?, argue that Luke uses such literary techniques more frequently than traditionally known, whether by evangelicals or skeptics!

In fact, Luke unambiguously does this very thing in Luke 3, by sandwiching verses 19-20, detailing John the Baptist’s future imprisonment, in the middle of the narrative regarding Jesus’ baptism. We know from Mark 1:9-11 that John the Baptist baptized Jesus, which must have happened prior to John’s imprisonment. Apparently, Luke is not afraid of reporting events in a non-chronological manner, to suit his own purposes, assuming that his readers would already know the exact historical chronology.

British bible teacher, Andrew Wilson, on the “Think” blog, pointed me to this new research done by David Armitage, and published in 2018, at the British evangelical think tank in Cambridge, Tyndale House. Armitage’s proposal has a number of exegetical and translation steps to make, but the more I think about it, Armitage’s idea is quite persuasive.

Jump on over to the Think blog to get the argument summary, but here below is Armitage’s proposed translation of Luke 1:80-2:7, that puts all of the pieces together. The chronological digression might be hard to pick out, so you may need to wait for the full explanation at the end of this post to get it straight. The main thing to look for is Luke 1:80 to 2:5, where the narrative jumps forward in time, following along the time period of John the Baptist’s upbringing, before resuming in verse 6, which chronologically follows after the narrative of where John the Baptist’s birth ends, described in Luke 1. It starts with the story of the young, John the Baptist, as he was growing up (notice how chapter headings, first introduced in our Bibles by, Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, in the 13th century, can be misleading):

- 1:80 The child [John the Baptist] grew and was strengthened in spirit, and he was in the wilderness until the day of his public appearance to Israel. 2:1 As it happens, it was during that time that a decree went out from Caesar Augustus to register all the Roman world 2 (this was the first registration, when Quirinius was governor of Syria), 3 and everyone went – each into their own town – to be registered. 4 Joseph also went up: out of Galilee, away from the town of Nazareth, into Judea, to David’s town (which is called Bethlehem) because he was from the house and family of David; 5 he went to be registered with Mary (she who was his betrothed when she was pregnant).

6 Now, it transpired that the days were completed for her to give birth when they were in that place, 7 and she gave birth to her firstborn son and wrapped him in cloths and laid him in a feeding trough, because there was insufficient space for them in their lodging place.

Compare with the ESV translation, and see what you think:

-

80 And the child grew and became strong in spirit, and he was in the wilderness until the day of his public appearance to Israel.

2:1 In those days a decree went out from Caesar Augustus that all the world should be registered. 2 This was the first registration when Quirinius was governor of Syria. 3 And all went to be registered, each to his own town. 4 And Joseph also went up from Galilee, from the town of Nazareth, to Judea, to the city of David, which is called Bethlehem, because he was of the house and lineage of David, 5 to be registered with Mary, his betrothed, who was with child. 6 And while they were there, the time came for her to give birth. 7 And she gave birth to her firstborn son and wrapped him in swaddling cloths and laid him in a manger, because there was no place for them in the inn.

The most troublesome verse for me is verse 5, as the ESV follows the standard interpretation, by describing the condition Mary was in, during the Quirinian census, that of being pregnant with Jesus. But Armitage argues that the Greek allows for a different translation, with a parenthetical comment, that simply reminds the reader of who Mary was, with no immediate time reference implied. This sets us up to read verse 6 as a transition, implicitly ten years prior, back to the main narrative, emphasizing the place of Jesus’ birth, Bethlehem, and not the timing. I am no Greek scholar, but this is very intriguing! Armitage paraphrases verse 5 like this:

-

Joseph went there to register with Mary – that same Mary, you will recall, who whilst betrothed to him was pregnant.

Objections to Armitage’s reconstruction might focus on the complex number of interpretive steps required. However, the whole solution is actually simpler, if we grant that Luke has a habit of sometimes jumping around chronologically in his narrative, for reasons clear to his original audience, that are not always intuitive to more contemporary readers. One big plus is that Armitage’s reconstruction adequately explains why Matthew’s account never mentions the Quirinian census; that is, Matthew never covers the events of Jesus’ life at age 10.

So, why does Luke insert this whole story about Joseph needing to go back to Bethlehem, some 10 years after Christ’s birth, before jumping back in with the rest of the Christmas birth story? Well, it would have been important for Luke to establish that Joseph was originally from Bethlehem, despite Jesus having grown up in Nazareth. Bethlehem was the city of David, associated with the prophecy in Micah 5:2, that indicates that the promised Messiah would come from Bethlehem.

Luke probably made it a point to mention the Quirinian census, because it would have identified Bethlehem as being place where Joseph had some family property interests. Just as residency or property interest requirements make a difference in our day, as to the cost of college tuition, taxation purposes, etc., it is certainly plausible that Joseph would have felt it necessary to go to Bethlehem, during the Roman occupation of Palestine in the 1st century, to defend his family property interest. Since the Roman census in 6 A.D. would have been a well-known event in 1st century history, it would have reinforced the idea of Jesus coming originally from Bethlehem, being born there a few years earlier.

If Armitage’s proposal holds, and he admits that it is far from being certain, this is what he says his revised chronology looks like. It totally reframes one of the most well-known Bible stories, of all time, but it solves a particularly knotty, chronological problem:

-

- Towards the end of the reign of Herod the Great, Mary – who is from Nazareth – encounters an angel who foretells Jesus’ birth.

- Mary visits Elizabeth in the Judean hill country, then returns home.

- Although already found to be pregnant whilst betrothed, Mary marries Joseph – a man from Bethlehem – who initially takes Mary to his family home.

- Jesus is born in Bethlehem; because of space restrictions in their quarters, Mary and Joseph place the baby in a feeding trough in the main living area.

- The family subsequently relocate to Nazareth, establishing there a home of their own.

- Several years later, when Quirinius is governing Syria, an enrolment is announced, so Joseph and Mary travel to Bethlehem, because this remains the location of Joseph’s family home, and he needs to register in connection with property there.

Pretty cool, huh?

UPDATE December, 2021: I first published this story three years ago. To my knowledge, Armitage’s proposal has not admittedly won over other scholars…. but neither has it met wholesale rejection either. Time will tell if this proposal resolves this long-standing “Bible discrepancy.”

Additional Resources:

I wrote about the Quirinius question five years ago, but David Armitage’s new solution is by far, the most persuasive, in my view…. A couple of other twists to the birth narratives: The traditional story of Jesus’ birth, as told in many Hollywood movies, tries to smash together the events recorded by Matthew and Luke, such that you have Luke’s shepherds together with Matthew’s wise men from the east, gathered around the newborn Jesus. It makes for a tidy story, until you start comparing Matthew and Luke together, a well-known difficulty for students of the Bible. Matthew has no shepherds, and Luke has no wise men! More than likely, the visit with Matthew’s “wise men,” or more specifically, “magi,” was a separate event, happening weeks, if not months, after Jesus’ birth. This places the trip to Egypt, as described in Matthew, at some undetermined time after the birth of Jesus, yet prior to the permanent settlement in Nazareth, an historical detail that Luke simply ignores. As another example, a growing consensus among Bible scholars has pretty much rejected the popular, traditional idea, of Joseph and a pregnant Mary going up and down the streets of Bethlehem, looking for a place to stay, only to be finally turned away at the “inn.” Contemporary scholarship makes the more modest claim that there was no available “guest room” for the family to stay in at relatives in Bethlehem, a correction made explicit in the NIV 2011 translation of Luke 2:7 (The ESV keeps the more traditional “inn,” but puts “guest room” in a footnote; see above, but according to New Testament scholar, Ian Paul, the evidence favors the “guest room” translation).