Fired up by enthusiasm, the theology of “the baptism in the Holy Spirit,” is taking over the globe. But what is it exactly? (photo credit: Getty Images, Economist magazine)

After a break for a few weeks, we are picking up again with the third in a multipart blog series….

Azusa Street. Los Angeles, California. April, 1906. A new African American preacher in town, William J. Seymour, a son of former slaves, stood up to preach for several nights in a row. Seymour had been blinded in one eye, due to contracting small pox, when he was young. But this did not deter Seymour from delivering his message.

According to Seymour, many churches in his day were spiritually dead. The movement of the Spirit was not to be detected. Teenagers were bored by long, droning sermons. Petty squabbles consumed the energies of church people. Spiritual lifelessness had permeated congregations. Even in Los Angeles, churches were strictly divided along the lines of race. Something was severely lacking in the churches of early 20th century America.

Seymour began preaching for revival.

Crowds began to gather to hear Seymour preach. The meetings were so packed that the small buildings where they met started to crack, and larger meeting places were sought after. The emotional excitement was electrifying. People gathered from all backgrounds in the hundreds. Rich and poor, men and women, black and white, all gathered together to experience the movement of the Spirit. Economic, racial and other barriers collapsed as people were somehow…. moved by the Spirit.

The Beginnings of the Modern Pentecostal Movement

But how were people “moved by the Spirit?” Seymour’s message was controversially radical, particularly for his day. In earlier periods of church history, some revivals were known to have been marked by unusual happenings. “Speaking in tongues,” whereby participants began to speak in unknown languages, were reported in all sorts of revivals. In 1906, William Seymour claimed to have experienced “speaking in tongues” himself. His followers began to do the same. Many of those who came to the Azusa Street Revival were forever changed.

Seymour had his critics. Many other Christians were skeptical, decrying the revival as permeated by excessive emotionalism. Yet what made Seymour’s message particularly controversial was that he associated “speaking in tongues” with receiving “the baptism in the Holy Spirit.” We read in the Book of Acts something that looked like what was happening those days on Azusa Street. Following the Resurrection, Jesus had instructed his followers to wait in Jerusalem.

- “And while staying with them he ordered them not to depart from Jerusalem, but to wait for the promise of the Father, which, he said, “you heard from me; for John baptized with water, but you will be baptized with the Holy Spirit not many days from now.“(Acts 1:4-5 ESV)

When the Jewish festival of Pentecost arrived, something incredible took place:

- “And suddenly there came from heaven a sound like a mighty rushing wind, and it filled the entire house where they were sitting. And divided tongues as of fire appeared to them and rested on each one of them. And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues as the Spirit gave them utterance.“(Acts 2:2-4)

Seymour had not been academically trained as a theologian, though a few years earlier in Texas, he took a six-week training class from a Charles Fox Parham, a pioneer evangelist preaching about the “baptism in the Holy Spirit.” Based of Seymour’s experience, and Parham teachings, Seymour’s theology came together. What was happening along Azusa Street matched what had happened on the day of Pentecost, in his mind. Contemporary Pentecostalism was born in those days in Los Angeles, and despite occasional periods of decline, the movement has continued to grow ever since, in some shape or form, into a worldwide phenomenon.

Seymour’s Pentecostalism remained outside of the established churches, however. Seymour, and others like him, insisted that this “speaking in tongues” was the marker of genuine Christian experience. Technically, the “baptism in the Holy Spirit” happens after conversion, according to Seymour’s Pentecostal tradition. But because the “baptism in the Holy Spirit” had been traditionally understood to be synonymous with Christian conversion, or regeneration, Pentecostalism began to be associated with the generally misleading idea that “speaking in tongues” was the sign of when someone truly becomes a Christian. Most established evangelical churches, therefore, did not welcome the movement, as this teaching appeared to suggest that those who were not speaking in tongues were not truly Christians. Pentecostals, in turn, looked upon the Christian mainstream as “quenching the Spirit,” and so they largely remained on the margins.

The Charismatic Renewal Movement

Fast forward, to a few decades later.

In nearby Van Nuys, California, the Pentecostal experience finally broke into the Christian mainstream. Around 1960, Dennis J. Bennett, a rector of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, had the same type of experience of “speaking in tongues.” But unlike William Seymour’s reputation on Azusa Street, Bennett urged followers to remain in their traditional churches and work for spiritual renewal. For Bennett, like Seymour, the “baptism in the Holy Spirit,” associated with Pentecost, was not the same thing as becoming a Christian. Instead, the “baptism” was something that God wanted to give to every believer, so that they might experience the “gifts of the Holy Spirit,” generally after conversion.

Radio evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson (1890-1944), and Pentecostal preacher.

(Photo credit: Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

Don Basham, in his 1971, Ministering the Baptism in the Holy Spirit, summed up the teaching this way: “We are not talking about the introductory ministry of the Holy Spirit to the unbeliever—we’re speaking of the subsequent empowering ministry of the Holy Spirit for the believers” (p.17). Furthermore, “it is the intent of God that every person receiving the baptism in the Holy Spirit should experience the miracle of speaking in tongues” (p. 33).1 Therefore, “speaking in tongues” was regarded as being the initial or confirming sign of “the baptism in the Holy Spirit,” as a “second blessing” experience for the Christian.

As I described in a previous blog post in this series, this was the idea that my high school friend, whom I had became reacquainted with in college, was talking about. She had acknowledged that I was a Christian, but that I had yet to receive the “full Gospel” experience.

The term “charismatic,” derived from the Greek word for “gift”, “charis,” was soon coined to describe what was going on in mainstream churches. The charismatic movement was able to overcome the tendency towards separation, from the mainstream churches, that the older Pentecostal movement was unable to avoid.

Over the years, this charismatic renewal movement swept through many different churches, like the wind, so to speak. Today, the combination of the older Pentecostalism and the newer charismatic movement continues to expand around the globe, representing the fastest growing expression of Christianity in the entire world. A Pew Research Center study in 2011 indicates that just over 25% of all Christians in the world today identify with being “Pentecostal” or “Charismatic. That means that 1 in 4 Christian believers have had some sort of charismatic experience in their lives.

From Charismatic Renewal to a “Third Wave” of “Signs and Wonders”

However, a growing consensus among evangelical scholars today question the identification of the contemporary phenomenon of “speaking in tongues” with the Pentecost experience of the church in Acts 2. Continuing on in Acts 2, we read:

- “Now there were dwelling in Jerusalem Jews, devout men from every nation under heaven. And at this sound the multitude came together, and they were bewildered, because each one was hearing them speak in his own language. And they were amazed and astonished, saying, “Are not all these who are speaking Galileans? And how is it that we hear, each of us in his own native language? Parthians and Medes and Elamites and residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya belonging to Cyrene, and visitors from Rome, both Jews and proselytes, Cretans and Arabians—we hear them telling in our own tongues the mighty works of God.”“(Acts 2:5-11 ESV)

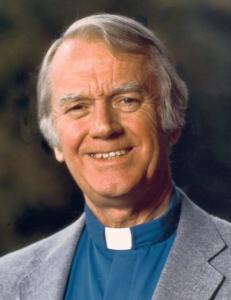

Dennis Bennett, the Episcopal priest who helped to initiate the charismatic revival movement in the 1960s (credit: Wikipedia)

In traditional Pentecostal or charismatic practice, the “speaking in tongues” phenomenon is a form of glossalalia, a Greek word for “speaking in an unknown language.” This could be either in terms of verbal speech given in a worship service, afterwords requiring some form of interpretation/translation to a known language of the congregants, to validate the strange speech, or in terms of a “private prayer language,” for personal use. But what we read in Acts 2 is something different. Acts 2 has a form of xenolalia, “speaking in a known language or languages,” such Parthian, Median, etc., all languages known to exist during the 1st century era of the Roman empire.2

As a result, the charismatic movement over the last thirty years or so has put less of an emphasis on glossalalia as being the initial sign of receiving “the baptism in the Holy Spirit.” Nowadays, the gift of tongues may be associated with “the baptism in the Holy Spirit,” or it may come later, or it may not even come at all! Some theologians refer to this modification of the Pentecostal and charismatic movements as being the “third wave” of the modern revival of “the gifts of the Spirit,” otherwise known as “the signs and wonders” movement.3

As a result of the relatively less controversial “third wave” movement the traditional lines of separation between Pentecostalism and the charismatic movement have tended to blur in recent years. More and more traditionally “Pentecostal” churches are playing down “speaking in tongues,” while still emphasizing less controversial, though no less dramatic, demonstrations of “the gifts of the Holy Spirit.”

John Wimber (1934-1997) founded the Vineyard Church, now a worldwide movement that spearheads the revival of “signs and wonders,” in the charismatic “Third Wave.” (credit: Wikipedia)

Examining the charismatic movement teaching about “the gifts of Spirit” is worthy of a detailed study. Are the miraculous “gifts of the Holy Spirit” still in operation today? This is a good question, but I will not go into addressing it on this series of blog posts. Rather, I want to keep the focus on the foundational doctrine of “the baptism of the Holy Spirit,” specifically, as this is primarily where the confusion lies.

What is “Spirit baptism?” Is it the same thing as conversion, the initial experience of faith in Christ, or is it a subsequent experience in the life of the Christian? As a way of approaching these questions, we need to look a little more at this idea of a “second blessing,” and where it came from. Stay tuned for the next blog post in this series.

Notes:

1. Don Basham was very active with the Full Gospel Businessmen’s Association, and a close associate with Derek Prince, a well-known leader in the charismatic renewal movement of the 1970s. However, the most popular books promoting charismatic renewal in the period around the 1970s were written by Dennis Bennett himself (along with his wife, Rita, often as co-author), Nine O’Clock in the Morning and The Holy Spirit and You.↩

2. Some defenders of the more traditional Pentecostal/charismatic view contend that Acts 2:4 suggests that the disciples were speaking in unknown tongues, but that the people gathered in Acts 2:6 heard the speech miraculously in their own known languages. In other words, we have two miracles: the first is the unknown speech uttered by the speakers, and second is the ability of the audience to hear what was spoken in their familiar dialect. Such a solution to insert glossalolia is ingenious, but it appears to be pure conjecture, with no evidence from the text to support it. Luke’s point here is to emphasize what happened to the believers, who had waited for the coming of the Holy Spirit, and not on some miracle experienced by the then unbelieving audience, who initially as observers, were then drawn in by Peter’s message. ↩

3. It should be noted that “speaking in tongues” is not always explicitly mentioned when different people in the Book of Acts encounter the Holy Spirit. We do see it mentioned in Acts 2 (Pentecost), Acts 10 (Caesarea/Cornelius), and Acts 19 (Ephesus). But there is no explicit mention of tongues in Acts 8 (Samaria) or Acts 9 (Paul’s conversion), though some scholars contend that tongues is strongly implied. For example, in Acts 8, why would Simon the Magician offer money for having the Spirit, if there was not an outward miraculous manifestation of the Spirit on display?↩

July 2nd, 2017 at 10:51 am

Clarke,

Glad to see you back on point with this topic. On a minor point as to your mention of the Acts 2 experience being one of zenolalia, I have often wondered if it was a miracle of “hearing” rather than speaking. Any thoughts?

Jerry

LikeLike

July 2nd, 2017 at 1:53 pm

Jerry: I address that possibility briefly in footnote #2 in the post.

It is certainly a possibility of there being two miracles, first the speaking in the unknown tongue, by Jesus’ disciples, and then a second miracle, with the listeners hearing them in there own languages. But the text makes no mention of two separate miracles.

Some might suppose that the disciples were actually speaking in a known language, like Greek or Aramaic, a non-miracle, which was then “heard” by hearers miraculously in their own language. This argument does not help the traditional Pentecostal view, but it is interesting to consider. Yet again, the text makes no mention of this.

This idea of a separate miracle of “hearing” is not new. Apparently, the Protestant Reformer, John Calvin, had heard (no pun intended) of this idea. But for Calvin, and as for many other commentators since, they reject this view as conjecture, as there is no evidence to support it.

I would remain somewhat ambivalent as to the miracle of “hearing” view, except for this: It turns the meaning of the passage upside down. The intent of the miracle is focused on the speakers, not the hearers. The Holy Spirit comes on the disciples, gathered there, waiting for the Spirit to come. To shift the emphasis to the hearers, completely misses the point of the passage. The hearers eventually respond in faith, but this is after the fact of the Pentecost miracle of tongues.

LikeLike

July 3rd, 2017 at 9:33 am

Clarke,

Sorry I missed the footnote. I agree the passage seems to address the speakers; however, there appears to be a multitude of listeners with various languages represented. So that would present a challenge for the speakers unless they were alternating speaking the various languages amongst themselves over a period of time. Does that make sense?

Jerry

LikeLike

July 3rd, 2017 at 9:55 am

Jerry: It does make sense. Perhaps your concern is that the Holy Spirit only fell on the 12 apostles (including the recently selected Matthias, from Acts 1). If that is the case, then your point is well taken.

However, there is good reason to think that that Holy Spirit actually fell on a larger group of disciples, there waiting in the Upper Room, and not just the 12. Acts 1:15 says that there were about 120 gathered. With 120 tongues speakers, that would more than cover the variety of languages spoken in Acts 2.

The key to resolving this is in identifying the referent of the pronoun in Acts 2:1: “When the day of Pentecost arrived, they were all together in one place.”

Who were the “they?”

If the “they” refers to just the apostles, mentioned at the end of the prior verse, Acts 1:26, then my proposed solution has a problem. However, on the other hand, the “they” could also refer to the entire company gathered in the Upper Room, i.e. the 120, and then the difficulty is resolved.

What do you think?

Clarke

LikeLike

July 3rd, 2017 at 10:46 am

Agreed.

Thanks

Jerry

LikeLike