From the Christianity Along the Rhine blog series…

Zwingli was in a tight spot. With radical Anabaptists on the one side and Roman Catholic papist defenders on the other, Zwingli saw himself as a defender of true reformation. He rejected what he perceived to be the excesses of Rome, while pushing back against the dangerous foolishness perpetrated by the Anabaptists, like his former friends, Konrad Grebel and Felix Manz. In his mind, his way was a moderate path between two extremes. It was with this posture that Zwingli hoped to form an alliance with his contemporary Reformer from Germany, the former Augustinian monk, Martin Luther. But such a dream was not to be realized.

Following the first part of a two-part “travel blog” series, we now look a bit more at the story of Huldrych Zwingli of Zurich, and what led towards his tragic end.

Zwingli’s statue in Zurich, with the Grossmünster Church where he preached, in the background, towering above on the right. My photo from October, 2025.

Clashing Visions of Reform: The Swiss Huldrych Zwingli and German Martin Luther

The Swiss Zwingli and the German Luther operated independently, while both were originally drawn into reformed thinking through the work of Desiderius Erasmus. Erasmus had published a new authoritative Greek New Testament. Both Zwingli and Luther devoured Erasmus’ writings, springing them into action, hoping to reform the Roman church. Both men reasoned that an appeal to Scripture, and Scripture alone, would guarantee the right path to genuine reform. But it soon became apparent that the two preachers would not be able to agree. There was no “we agree to disagree” sentiment at this stage of Protestantism, particularly on serious matters like the Lord’s Supper.

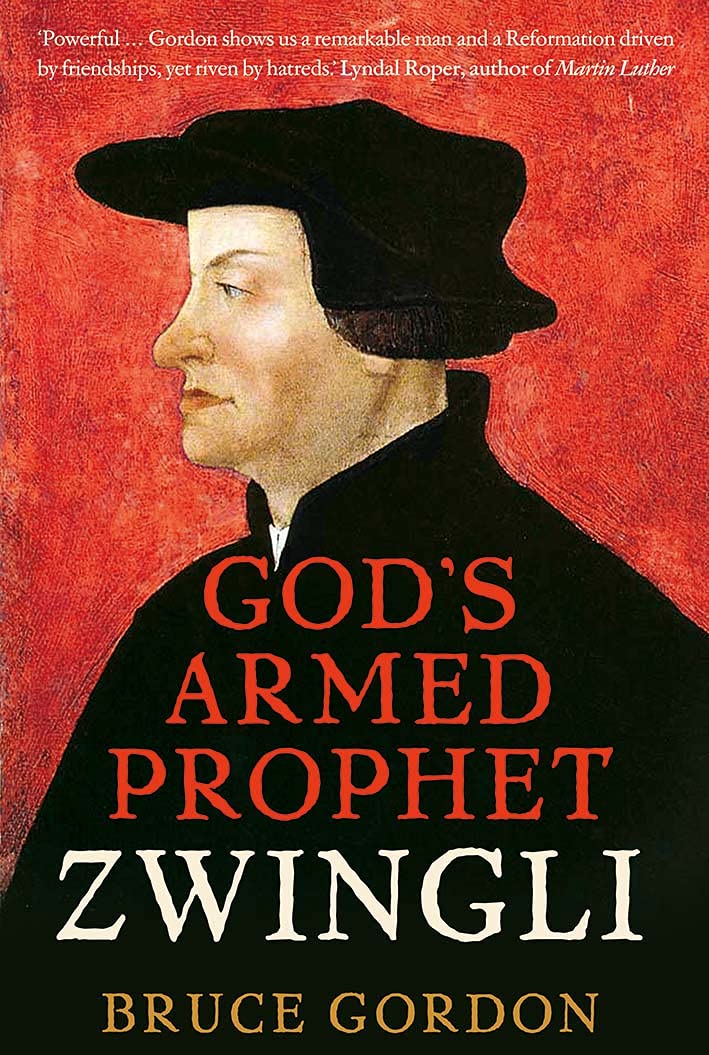

Yet some of the disagreements were relatively minor. According to Bruce Gordon, author of Zwingli: God’s Armed Prophet, there was to be no singing in Zurich’s churches, unlike what was taking place in Luther’s Wittenberg. Zwingli’s singing-free worship was based on his appeal to Amos 5:23:

“Take away from me the noise of your songs; to the melody of your harps I will not listen.” ‘What would the rustic Amos say in our day,’ asked Zwingli, ‘if he saw and heard the horrors that were being performed and the mass priests mumbling at the altar…Indeed, he would cry out so that the whole world could not bear his words.” (Cited by Gordon, p. 140).

Even more moderate Reformed churches sympathetic to Zurich, with contemporary colleagues like Martin Bucer in Strasbourg and Johannes Oecolampadius in Basel, would not go as far as Zwingli and ban all singing. Yet contrary to common opinion, Zwingli did not hate the arts. He was a fine musician himself, and he “had a deep conviction that music had a power over the soul like no other force” (Gordon, p. 140). Zwingli’s own music was composed for house gatherings, not congregational worship settings (Gordon, p. 141). Luther, on the hand, composed music for corporate worship, hymns which have endured to this day.

Luther’s engagement with Erasmus eventually turned sour, just as Zwingli’s relationship with Erasmus did, but over a different issue. Luther disputed Erasmus over the doctrine of election, articulated in Luther’s Bondage of the Will, leading Luther to have a strong view of predestination. Like Luther, Zwingli believed that “according to God’s pleasure and will, hidden from all humans, the election of some and not others was decreed before the moment of creation. Predestination therefore preceded faith, as only those whom God chose would come to believe” (Gordon, p. 158). However, Zwingli was not as strident as Luther, and from what can be gathered from his writings did not clash with Erasmus on election. Instead, Zwingli put an emphasis on divine providence.

“[Zwingli] was repeatedly optimistic: God is good and benevolent, inviting humanity into his revelation. Men and women can have absolute assurance in divine providence, which orders all things for the good and without doubt. God is absolutely provident or is not God” (Gordon, p. 180).

So, Zwingli and Luther had their differences. But could those differences be worked out?

Zwingli rarely left Zurich, mostly out of concern for his safety, as he was a wanted man in traditional Roman Catholic circles. But Zwingli wanted to find out if he and Luther could find common ground, in order to further the advance of genuine reform against what both saw as a corrupt papacy. Zwingli was hopeful that he and Luther would be able to get along well. Both parties agreed to travel at the invitation of Philip of Hesse in Marburg, in order to have a dialogue. However, both men were already aware of what the other thought about the Lord’s Supper, and the two differed substantially.

The story goes that Zwingli removed the organ from the Grossmünster Church, taking music out of the church, only to eventually return the organ years later. Ironically, Zwingli was a rather accomplished musician himself, writing songs for private use, but who believed that medieval church practices had warped the use of singing in worship.

Zwingli and Luther at the Marburg Colloquy

When the two arrived at Marburg, along with other reformed thinkers, it soon became apparent that things were not going to go well. Zwingli had been cautiously optimistic that both he and Luther were saying pretty much the same thing, and that some kind of agreement could be worked out. Luther, on the other hand, had prejudged Zwingli to be a fanatic, showing no real desire for anything which suggested compromise, primarily on the Lord’s Supper.

Both Zwingli and Luther rejected the medieval doctrine of transubstantiation, but little common ground was found with respect to anything else regarding the Lord’s Supper. For Luther, Jesus’ own words “this is my body,” as in Luke 22:19, as Paul’s same language in 1 Corinthians 11:23–25, was to be taken at face value. This was no mere symbolism for Luther. “Christ had meant what he said” (Gordon, p. 175). Christ was and is indeed physically present in the sacred meal.

Zwingli appealed to John 6:63, “The flesh profits nothing,” to make the more symbolic argument:

“At heart was an unshakeable conviction that Christ could not be physically present in the bread and wine of the meal….after his resurrection the Son ascended to the right hand of the Father, as the creeds of the Church declared….The meal, Zwingli believed, was a memorial to Christ’s passion and resurrection, to the salvation of the faithful….For centuries, Christian theologians had rejected the Passover as having no place in the Church. For Zwingli, it was the key to understanding Christ’s meal” (Gordon, p. 170-171).

Luther dismissed Zwingli’s response as depending on a form of human reason that could not demonstrate any article of faith. To say that Christ could not be in the world, because he sat at the right hand of the Father was utterly false (Gordon, p,. 175). Luther’s rejection of Zwingli was harsh, describing the Swiss preacher as “perverted” and “lost to Christ“:

“I testify on my part that I regard Zwingli as un-Christian, with all his teachings, for he holds and teaches no part of the Christian faith rightly. He is seven times worse than when he was a papist” (Cited by Gordon, p. 176).

An impasse was reached. While other theological matters were largely agreed upon, the controversy over the Lord’s Supper could not be resolved. A statement was drafted that both Zwingli and Luther could agree that Christ is present at the Lord’s Supper, but that was only a tenuous matter that could not be held together for long. Full reconciliation was lost. Zwingli broke down in tears, wishing that both men could still find some common bond of friendship. Luther, on the other hand, could not see Zwingli as a fellow brother in Christ. Zwingli had willfully denied the teaching of Scripture, crossing a line for Luther in the mind of the preacher from Wittenberg (Gordon, p. 179-180).

The gap between Zwingli and Luther only widened after the Colloquy of Marburg. Zwingli had a more humanist background than Luther, believing that in some cases even pagans could be saved. In an effort to win over the King of France to the Zurich cause, Zwingli had listed the King of France, as well as pious pagans of history like Socrates and Cato, as being among God’s elect. Luther was scandalized by Zwingli’s willingness to believe that such “idolaters” were among the saved (Gordon, p. 238-239). Like his one-time mentor, Erasmus, Zwingli was enamored by the classical world, believing that the greatest thinkers of the Greco-Roman past, prior to the emergence of New Testament Christianity, were essentially in alignment with Christian values and mindset.

With hopes for reconciliation with Luther dashed at Marburg in 1528, Zwingli continued out on his own in his opposition to the papacy. Yet Zwingli had grown more strident in his resolve against his Protestant critics. In particular, his patience with the Anabaptists had run out. Just two years earlier in 1527, his former friend, Felix Manz, was publicly drowned in Zurich by city officials after being re-baptized. Zwingli made no effort to intercede on behalf of his old friend.

Shortly before his death, Manz wrote a letter with a stinging critique of Zwingli:

“Unfortunately, we find many people these days who exult in the gospel and teach, speak and preach much about it, yet are full of hatred and envy. They do not have the love of God in them, and their deceptions are known to everyone. For as we have experienced in these last days, there are those who have come to us in sheep’s clothing, yet are ravaging wolves who hate the pious ones of this world and thwart their way of life and the true fold. This is what the false prophets and hypocrites of this world do” (Cited in Gordon, p. 191-192).

To the Anabaptists, Zwingli embodied the worst form of self-righteous bigotry one could imagine. Zwingli’s concern was just the opposite.

A female abbey was founded in Zurich in 853. But in the early 16th century, preaching from Zwingli ended up encouraging the abbess to dissolve the abbey, and the property became the Fraumünster Church.

Zwingli Against the Anabaptists

Zwingli’s response was just as caustic, casting the Anabaptists as having the spirit of antichrist, by citing 1 John 2:19: “They went out from us, but they were not of us” (Gordon, p. 192, wrongly cites this as being from the Gospel of John). Behind all of Zwingli’s polemic against the Anabaptist desire for a pure church was Zwingli’s maturing view of the church visible and invisible, somewhat like what we find in various forms of Christian Nationalism today.

Zwingli viewed Anabaptism as a cancer which was hindering the true reformation movement, a cancer which must be eradicated. The spread of the Gospel was paramount, but it required the existence of a state sponsored church where non-believers and believers freely existed. There was no room for Roman Catholics and Anabaptists to practice their understandings of Christianity in Zwingli’s Zurich. Monasteries and nunneries were shut down in Zurich, whose inhabitants were encouraged to get married or otherwise leave the city. Catholics lost their seats on the city council.

Yet his Anabaptist critics faired no much better. Civil authorities in Zurich persecuted Anabaptists wherever they were found, with Zwingli’s blessing. The concept of religious freedom, so central to modern democratic visions of state/church relations, was completely foreign to Zwingli’s thinking.

In the year following the colloquy of Marburg, 1529, the emperor Charles V held a meeting with the Protestants in Augsburg, in hopes of trying to heal the breaches ruptured by the Protestant movement. Charles was terribly concerned that a breakdown in Europe would weaken the defence against the Turks who were on the doorstep of Vienna. Charles was hoping for a united Christendom to face the menace of the Turks, but instead the German Protestants gave him the Augsburg Confession. Charles rejected the Augsburg Confession, which became the defining confession of Lutheranism. But then there was Zwingli.

Zwingli submitted his own “Account of the Faith” for the Diet of Augsburg, where he took on all opponents, not just the Roman Catholics. For those who held to purgatory, they had no Christ. His views regarding the sacraments remained unchanged. Yet even friends of Zwingli, like Martin Bucer, were appalled by the intransigence of the tone in which Zwingli wrote. The Lutherans there realized that Zwingli had simply dug in his heels against them. Whatever agreement had been reached at Marburg, however fragile it was, had been broken by Zwingli. The Anabaptists were treated even far worse. Zwingli along with his Zurich city-state had become increasingly isolated (Gordon, p. 226-231).

Zwingli’s theology of how the state and church relate to one another was not entirely unique. During the medieval era in Western Europe, it was practically assumed that to be a European was to be Christian and to be a Christian was to be European, even with the presence of groups like the Jews which upset such a neat formula. Yet what made a number of Zwingli’s friends increasingly wary of the Zurich Reformer was Zwingli’s willingness to use force in order to defend his understanding of the church visible and invisible.

Even in the summer prior to Zwingli’s meeting with Luther in Marburg in 1529, hostilities between various Swiss city-states had broken out between Protestant and Catholic alliances, the First Kappel War. A peace was reached at the end of the conflict, but Zwingli believed the terms of the conflict to be an impediment to the spread of the Gospel.

Zwingli’s house: The marker above the door in English reads: “From this house he left on October 11, 1531 with the Zurich army to Kappel, where he died for his faith.”

The Death of Zwingli

Zwingli’s translation of the entire Bible into German began to be printed in 1529, even though the Swiss dialect could not compete with the influence of Luther’s Bible which came out a few years later (Gordon, p. 243). Zwingli fully believed that the cause of the Gospel was at stake, but it would take a military alliance among the Protestants to push back against Catholic resistance to Zwingli’s proposed reforms. But such an alliance seemed remote, as other Swiss Protestants hoped instead for peace and stability.

Failure of the Swiss Protestants to effectively unite emboldened the Swiss Catholic city-states to strike against Zwingli’s Zurich. By October, 1531, war had become inevitable. What began as a theological crisis with high hopes for reform some fifteen years or so earlier devolved into open military warfare. The city of Zurich sent troops out to meet the Catholic war party, and Zwingli donned armor as well and joined the Zurich military effort. When the defeated Zurichers returned later from the battle of the Second Kappel War, Zwingli’s wife Anna learned that she had lost son, her brother, her brother-in-law, and ultimately her husband, Huldrych Zwingli.

Zurich was ordered to pay reparations to the Catholic war effort, and while Zwingli’s reforms were not completely rolled back, Zwingli himself was blamed for the calamity inflicted upon Zurich. The people in the rural areas under Zurich’s influence were particularly incensed. They drafted a resolution forbidding any clergyman from meddling in civic and secular affairs, a clear rebuke against Zwingli’s memory (Gordon, p. 251-252).

Zwingli’s friends, like Martin Bucer in Strasbourg, lamented Zwingli’s death. Nevertheless, even Bucer in a letter to another reformer wrote about his disappointment with Zwingli’s proclivity towards war:

“I feared for Zwingli. The gospel triumphs through the cross. One deceives oneself when one expects the salvation of Israel through external means with impetuosity, and triumph through weapons . . . It greatly unsettles me that our Zwingli not only recommended the war but did so incorrectly, as it appears to have been the case, and if we are rightly informed” (Cited by Gordon, p. 258).

Luther’s response in Wittenberg to Zwingli’s death was not at all conciliatory. He was convinced that Zwingli died in sin and great blasphemy, as he wrote in his Table Talk:

“I wish from my heart Zwingli could be saved, but I fear the contrary; for Christ has said that those who deny him shall be damned. God’s judgment is sure and certain, and we may safely pronounce it against all the ungodly, unless God reserve unto himself a peculiar privilege and dispensation. Even so, David from his heart wished that his son Absalom might be saved, when he said: ‘Absalom my son, Absalom my son’; yet he certainly believed that he was damned, and bewailed him, not only that he died corporally, but was also lost everlastingly; for he knew that he had died in rebellion, in incest, and that he had hunted his father out of the kingdom” (Cited by Gordon, p. 259).

Luther would not have been able to succeed in the reformation of the church without the assistance of the power of the state, that much is true. However, Luther was much more cautious in linking together the church and the state than was Zwingli. Unlike Zwingli, Luther championed a theory of two powers, a spiritual kingdom associated with the church, being exercised through faith and the Gospel, and a temporal kingdom governed by the state, being exercised through efforts to maintain order and restrain sin. For Luther, the church should not exercise secular power and the state should not interfere with matters of conscience, a type of distinction which Zwingli would not recognize.

Zwingli’s capable successor in Zurich, Heinrich Bullinger, was a friend of Zwingli, but wisely chose not to respond to Luther. Even when John Calvin eventually came along to Geneva, Calvin barely mentioned the name of Zwingli in his writings. Calvin sought to find common ground among Protestants without appealing to Zwingli’s controversial legacy.

Zwingli: God’s Armed Prophet, by Bruce Gordon. I highly recommend this biography of the Swiss reformer of Zurich

Reflections on Zwingli, Particularly with Respect to Baptism and Church/State Relations

Bruce Gordon ends his book, Zwingli: God’s Armed Prophet, with a look at how biographers have remembered Zwingli over the centuries, and he even offers a review of a fairly recent movie about Zwingli’s life, one that I can highly recommend (in German, but you can find a version with English subtitles).

For me, Zwingli is in many ways a hero, a champion for preaching the Gospel, and an ardent supporter of verse-by-verse exposition of the Bible. He shocked his hearers when he set aside the standard medieval lectionary for preaching from certain texts of Scripture, and instead started with Matthew, chapter one, and worked his way verse-by-verse through the New Testament during his weekly Sunday sermons.

Zwingli did the right thing here. He did not skip over parts of the Bible that were uncomfortable. If the text mentioned something in his verse-by-verse analysis, he would address it straight from the pulpit. Today, many pastors stay away from verse-by-verse expository preaching, and stick to purely topical approaches to Scripture. Technically, there is nothing wrong with topic-oriented preaching, and topic-oriented preaching can offer a good change of pace. But the problem is that topic-oriented preaching often forces the preacher to skip over things in the text of Scripture that do not nicely fit in with the topic being focused upon. Zwingli, on the other hand, faced what was presented to him in his Bible head-on, with no skipping the hard stuff. Preaching from the text verse-by-verse leaves you with no other alternative. That, in and of itself, helped to spark the Reformation in his church in Zurich, creating the Protestant movement among the Swiss.

Yet Zwingli was a complex hero, with some serious rough edges. Zwingli remains a controversial and contradictory figure. I still puzzle over his views of the Lord’s Supper, preferring John Calvin’s third-way approach through the impasse between Zwingli and Luther. Luther overreached in his criticisms of Zwingli, but Zwingli could be just as stubborn.

Defenders of Zwingli say that the Zurich preacher was not a mere memorialist when it comes to the Lord’s Supper, and was willing to at least acknowledge the spiritual presence of Christ in the sacrament. Perhaps he was. But it is difficult to reconcile this with the tendency in certain Protestant circles, following Zwingli, to downplay the role of the Lord’s Supper in Christian worship, contrary to the historic emphasis on weekly celebration of the eucharist which has united the church for many, many centuries.

In my view, Erasmus was correct to be wary of Zwingli’s insistence on his own understanding of the perspicuity of Scripture. Scripture is indeed clear on the central articles of Christian faith. But Zwingli was naive to think that every Bible-believing person should simply be able to draw the exact same conclusions regarding the teaching of Scripture, which were in perfect alignment with Zwingli’s own interpretations of Scripture.

There is certainly a genuine interpretation of each and every passage of Scripture, based on the original intentions of the author, but every interpreter of the Bible must acknowledge their own fallibility when it comes to handling the text of the Bible. The Scriptures are indeed without error, but our human interpretations of the text are still prone to error, so each of us should approach the Bible with a sense of exegetical humility. If Zwingli had himself this kind of exegetical humility, it might have led him to live a much longer life and avoid the stain of controversy which still tarnishes his otherwise influential legacy to this very day.

Zwingli’s contradictions make him a fascinating figure to study. In many ways, I concur with much (though not all) of Zwingli’s understanding of baptism. Infant baptism does not save, but it does act as a New Testament parallel to the Old Testament understanding of circumcision.

Defenders of “credobaptism;” that is, “believer’s baptism,” who are critics of “paedobaptism;” that is, infant baptism, will often cite Colossians 2:12 in support of their view:

“….having been buried with him in baptism, in which you were also raised with him through faith in the powerful working of God, who raised him from the dead” (ESV).

As the argument goes, “baptism” is linked to the concept of having “faith,” therefore, baptism assumes that a candidate for baptism has exercised some form of believing faith, something which infants can not do. While there is substantial weight to this argument, it often ignores the verse prior to it which adds some important context, directly leading into verse 12:

“In him also you were circumcised with a circumcision made without hands, by putting off the body of the flesh, by the circumcision of Christ,….” (Colossians 2:11 ESV).

Paul is clearly linking the Jewish practice of circumcision with baptism in this passage. The Old Testament quite clearly shows that Jewish male infants were circumcised, so any opponent to paedobaptism must somehow wrestle with this, in how Paul is associating circumcision with baptism. But advocates of credobaptism have a good point to make in saying that we have no clear, undisputed New Testament example of infants being baptized.

I have good friends of mine who are pastors, who in good conscience, simply could not perform an infant baptism. I totally get that. In other words, different Christians standing in good faith hold to different positions regarding baptism.

Given the difficulty of resolving the debate over infant baptism, Zwingli’s unrelenting opposition to “believer’s baptism” comes off as most extreme. Zwingli’s efforts to stamp out the Anabaptists, standing aside as the state sought to violently punish these Anabaptists, was going way too far. Linking the power of the state with the enforcement of a contentious Christian doctrine clearly reveals the dangers of a Christian Nationalism, a lesson that Christians should be reminded of today.

Baptism is not a hill I am going to die on, and it should not have been for Zwingli either. Zwingli probably had the best of intentions. Perhaps Zwingli viewed the Anabaptists as a promoting a kind of “slippery slope” to spiritual anarchy, of some sort. Yet sadly, Zwingli weaponized baptism as a violent tool of the state, ultimately and utterly missing its Scriptural purpose.

The very nature of politics assumes that it is appropriate to use force to impose laws on people. Yet if people are not persuaded in their hearts and minds that a particular law is just, they will rise up in opposition to it. This is the very problem which Zwingli ran into, and which has since tarnished his otherwise remarkable legacy.

Far from squashing the belief in “believer’s baptism,” the opposite took place. The original Anabaptist impulse, which Zwingli tried to use the heavy-hand of the state to squelch, ended up unleashing a movement whereby “believer’s baptism” has become a very dominant feature of evangelical thought and practice in the 21st century.

—————————————————-

Charlie Kirk, outspoken Christian and political activist, in his last moments before being shot by an assassin. In my view, both Kirk and Zwingli had a lot in common.

Addendum: Is Zwingli A 16th Century Parallel to Charlie Kirk??

Zwingli’s fervent preaching of the Gospel, combined with his willingness to cozy up closely to the powers of the state, and even take up arms, should provide for us a cautionary tale. Within a month or so before our trip to Europe, walking the streets where Zwingli walked in Zurich, the Christian evangelist and conservative political activist, Charlie Kirk, was killed by an assassin. Videos of the shooting circulated for weeks on social media. The memorial service for Kirk held in Arizona featured speeches by both the American president and vice-president, with some 90,000 in attendance, while millions online viewed the service. The event was partly a Christian revival meeting, but also had the unmistakable tone of a political rally.

After my time in Zurich, upon reflection I think that Zwingli would have been right at home with Charlie Kirk’s blend of Christian revival and political conservatism. Zwingli, as a preacher, refused to stay in his lane, and combined his evangelical calling with political activism. Defenders of Zwingli celebrated his preaching of the Gospel. Zwingli’s message stirred up revival in a Switzerland living under centuries of medieval distortions of Christian faith. But his opposition to other sincere Christians who differed with him bred resentment from others.

A one-for-one correspondence between Zwingli and Charlie Kirk would be a misleading claim, as the circumstances of their respective deaths differ dramatically, and they lived in different cultural contexts. Nevertheless, the parallels between the two are striking. Both Zwingli and Kirk died as relatively young men. Both were evangelists. Both were strident in their beliefs, outspoken with their views, and were excellent communicators, organizers, and debaters. Both were known for their courage. Both lived with death threats issued against them. Both had close friends in high places. Both were fervent patriots. Both were misunderstood by many of their contemporaries.

Yet Zwingli’s wedding together of church and state proved to be an embarrassment for the great Reformer. Most people who think about the Reformation of the 16th century today immediately consider the names of John Calvin and Martin Luther. But Zwingli, who was just as influential, if not more so, has been a more controversial figure to grasp. Some 500 years later, Zwingli still remains relatively unknown.

Though separated by the centuries, the deaths of both Zwingli in the 16th century and Charlie Kirk in the 21st century have been tragic, even senseless losses.

The death of Charlie Kirk in September, 2025 ripped a hole in the American psyche. In many ways, the death of Huldrych Zwingli did the same thing for 16th century Europeans. It is extremely concerning when supposed Christians in response to Charlie Kirk’s death are acting out in ways that express violent rhetoric, as Christian apologist Jon McCray reported shortly after Kirk’s death:

I do wonder how many champions of Charlie Kirk today think about the complicated memory of Huldrych Zwingli, and what can be learned from the Protestant reformer of Zurich.

Some might think that my comments reflect a kind of wishy-washy, fake “third wayism,” which in some quarters gets a lot of harsh criticism today. If you want a helpful clarification as to what I am getting at, then take a few extra minutes and watch the following video by Christian apologist Gavin Ortlund, who makes a defense of the late Tim Keller, whose legacy has come under fire recently in the wake of Charlie Kirk’s death. Even if you come to the conclusion that a “third way” approach offered by a Tim Keller or Gavin Ortlund is inherently bad, at least make the step of acting in good faith and not misrepresent what a Tim Keller or Gavin Ortlund is saying:

Which is better: To be winsome and persuasive, or confrontational and combative? I favor the former over the latter.

Christians should be involved in the political process. But when Christians tend to elevate political concerns in such a way that the clear proclamation of the Gospel tends to get overshadowed and crowded out, great harm can be done. We can learn from church history, to avoid some of the terrible mistakes made in the past, a lesson we should not ignore. The story of Zwingli serves as a sobering example for us today.