From the Christianity Along the Rhine blog series…

On this Happy Reformation Day, we ask: Who was Huldrych Zwingli?

Huldrych Zwingli is not as well known as the two leading lights of the 16th century Protestant Reformation, Martin Luther and John Calvin. But among the Swiss, Zwingli was the most influential of the Reformers … until he was killed in battle at age 47.

But if he was such an important historical figure, why do so few Christians know anything about Zwingli?

I think I know why: The irony of Zwingli’s death was that he was caught between his pride of the Swiss people and his hatred of the mercenary movement, whereby various European powers would offer pensions to Swiss men to go off and fight their wars. In the end, a combination of his Swiss pride and theology of the church overtook his rejection of military service, and he died at the end of the sword, all while preaching the Gospel. He was Zwingli: God’s Armed Prophet, the title of a fascinating biography of the Swiss Reformer by Yale historian Bruce Gordon.

Zwingli: God’s Armed Prophet, by Bruce Gordon, is the most recent biography of the great Swiss Reformer of Zurich.

A Visit to Zurich, Switzerland

My wife and I took a trip to Europe in 2025, spending a few days in Zurich, Switzerland, where I got to explore the city where this relatively unfamiliar giant of the Protestant Reformation preached his sermons, lambasted by both the Roman papacy and fellow Reformer Martin Luther. This is the first of two “travel blog” posts covering the often forgotten Huldrych Zwingli.

The church where Zwingli preached in the 16th century, the Grossmünster, still stands in the center of the city of Zurich. After taking a boat cruise on Lake Zurich, which feeds the Limmat River, I walked up the road just a block or so alongside the Limmat. There I found a statue of the Reformer, with both a Bible and a sword in hand, sculpted by the Austrian artist Heinrich Natter, and dedicated in 1885.

Many historians do not know quite what to do with Zwingli. The idea of a pacifist-leaning preacher, who ironically was killed in battle, proved to be just one of the many contradictions of Zwingli, sidelining his historical memory among the Protestant Reformers. He upheld the authority of Scripture, and Scripture alone, but when confronted by more radical reformers that infant baptism was not explicitly taught in Scripture, Zwingli felt compelled to support efforts by the civil magistrates to have such radical reformers put to death. Zwingli was known to be a proficient musician, and yet he banned singing in worship in his Zurich church. In his earlier years, he had a spiritual conversion experience all while engaging in multiple premarital sexual relationships as a priest, and being rather unrepentant about it.

As a result of such embarrassments, it is hard to find the bulk of Zwingli’s written works translated into English. Not so with Luther and Calvin, whose books are translated widely and are still read today. Nevertheless, it is difficult to imagine how the Protestant Reformation would have taken off as it did without the intellectual talents of Zwingli driving it along.

Unveiled in 1885, a statue of Zwingli stands in front of the Wasserkirche, or “Water Church,” in Zurich. The Reformer has both a Bible and a sword in his hands. I had the opportunity to explore the old city of Zwingli’s Zurich in October, 2025.

Zwingli’s Early Years

While Martin Luther taught in Wittenberg, Germany, Zwingli became the “people’s priest” in Zurich, Switzerland. Both Luther and Zwingli had become enamoured with Desiderius Erasmus’ Greek New Testament, marking a drastic change in each man’s outlook on the Bible at nearly the same time. But in many ways, Zwingli was ahead of Luther. Zwingli married Anna a year before Luther married Katie. Zwingli’s Swiss German translation of the Bible preceded Luther’s German translation by several years.

Born in a Swiss alpine village in 1484, Zwingli excelled as a student, going off to school at age 10 in Basel, and then attending university in Vienna at age 14, before returning to Basel to finish his college education. At age 22, he became a priest in the Swiss community of Glarus.

It was in Glarus that Zwingli experienced the cultural dilemma of the Swiss people. Though Zwingli had a fairly modest and financially stable upbringing, most Swiss had difficulties making ends meet. As a result, many took up military service for hire, as representatives of the papacy in Italy and their opponents in France would seek out Swiss men to serve as mercenaries, offering them pensions, though only half would live long enough to return home. It was the most practical way a Swiss man could provide for himself and his family, by effectively selling themselves for a period of time as a slave to fight wars for other people. As a priest, Zwingli accompanied his people into battle, and he became disillusioned with the whole mercenary system.

After returning from one military disaster, Zwingli went to Basel to meet Desiderius Erasmus, to learn more from the man who gave the Western world a new authoritative Greek New Testament. Zwingli’s meeting with Erasmus set the trajectory for the rest of his life. Later that year, Zwingli moved to a Benedictine Abbey in Einsiedeln. It was during these few years when he experienced spiritual upheaval.

On the one side was the reform of Zwingli’s own spirituality, inspired by Erasmus’ work on the Greek New Testament. On the other side, Zwingli was caught up by the tensions of trying to live a celibate life as required of all medieval Catholic priests. However, it was commonly accepted that while priests were expected not to marry, they nevertheless had discreet sexual relations along the side. This was true for Zwingli as well. While in Einsiedeln, Zwingli got a woman pregnant, and was known to have fathered at least one illegitimate child. Nevertheless, God was starting to take a hold of Zwingli’s life while in Einsiedeln. Zwingli’s years in Einsiedeln prompted him to make a bold change in his life. That change led him to Zurich, Switzerland.

Zwingli Goes to Zurich: The “People’s Priest”

The opportunity came for Zwingli to become the “people’s priest” at the Zurich church, Grossmünster in 1518. His election to the position was almost derailed by rumours of his sexual past. Furthermore, he had only been preaching for several months before the plague swept through Zurich, and nearly killing Zwingli himself. Zwingli survived, viewing his recovery from the plague as a sign of God’s blessing.

Zwingli’s preaching took up reformation themes. He rejected the intercessory powers of Mary and the saints, denied the existence of purgatory, and assured his parishioners that their unbaptized babies were not damned.

Zwingli was not afraid of challenging other preachers. During one sermon delivered by a Franciscan monk regarding the veneration of the saints, Zwingli himself shouted down the speaker, “Brother, you are in error!” Zwingli’s strategy was to force a public debate with detractors, with hopes of enlisting support from the Zurich city magistrates. The strategy worked.

But his most controversial preaching was in objecting to the Swiss mercenary practice, and the obtaining of pensions for such service, as offered through outside entities, including the papacy. Though once a loyal servant of the papacy, Zwingli had slowly been transformed into an irritant in the eyes of Rome.

By 1522, he even secretly married a young widow, who already had several children, Anna Reinhart, a woman who had assisted Zwingli to recover from the plague. Zwingli no longer could abide by the celibacy requirement for priests established by Rome.

Notable public controversy ensued when that year he met with a group of friends, where the others in the group ate a meal of sausages, in violation of the rules of the Lenten fast. Zwingli did not partake, but it was evident that he was the primary instigator. His pursuit of reforms even caused trouble with his friendly correspondence with his mentor Erasmus.

Zwingli wrote to Erasmus believing in the perspicuity (or clarity) of the Scriptures. Erasmus in turn regretted the radical nature of Zwingli’s thought. Erasmus had urged for reform, too, but he still thought that no one could read the Scriptures on their own without assistance from the magisterial teaching authority of the church to properly guide the reader. Their differences led to a falling out for their friendship.

Erasmus had good grounds for being wary of Zwingli’s radical leanings as signs of instability. In 1520, Zwingli believed at first that the tithe was not sanctioned by the Bible, and could be abolished. But when more radical reformers took him up on rejecting tithing, Zwingli shifted and commended that civil magistrates could collect tithes, just as long as the civil powers did not exploit the people (Gordon, p. 96-98). A similar situation developed when Zwingli urged that ornate artistry be removed from the churches, as such imagery violated the second of the Ten Commandments. But when more radical reformers took Zwingli’s teaching to the next level and destroyed altars, such that the wood could be sold to assist the poor, Zwingli rejected such iconoclastic activities as threatening the stability of the social order (Gordon, p. 102).

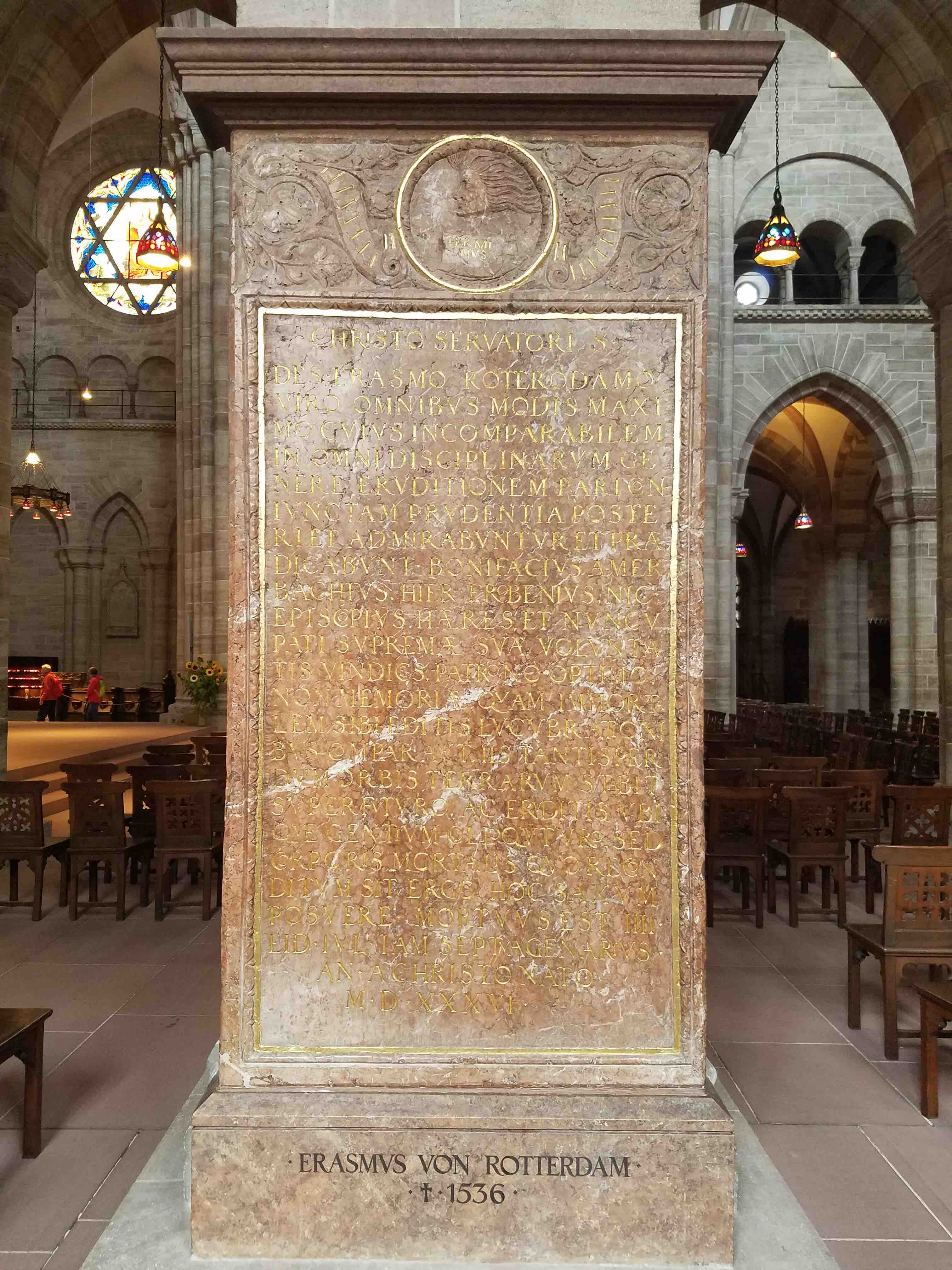

Desiderius Erasmus, the humanist who gave the Western world the first authoritative Greek New Testament in the 16th century, remained a Roman Catholic his whole life. Erasmus believed that Zwingli’s reforms had gone too radical, and broke his friendship with Zwingli. Nevertheless, when Erasmus died, he was buried in the city cathedral of Basel, Germany, a Protestant church, a remarkable gesture suggesting that Protestants and Roman Catholics are not as far apart as is commonly believed. … After two days in Zurich, my wife and I traveled to Basel, where I saw Erasmus’ grave here.

The Church Visible and the Church Invisible

Part of Zwingli’s shifting views on tithing and iconoclasm were a result of his developing views on the nature of the church. Zwingli believed in the church visible and the church invisible. The church visible was made up of people who attended church and participated in a Christian society. The church invisible were those genuine believers and followers of Jesus living among the church visible. Zwingli’s theory of how the state related to the church depended on this visible/invisible distinction. The more radical reformers, inspired by Zwingli, such as the Anabaptist leaders Konrad Grebel and Felix Manz, rejected infant baptism as being not taught in Scripture in their view, and urged true believers to take on adult baptism. These Anabaptists were rejecting their infant baptisms as valid, much to the consternation of Zwingli who saw the Anabaptist movement as a threat to his understanding of the visible church.

Zwingli saw the church as a parallel to the ancient Israelites. Just as circumcision was the primary identity marker for Old Testament Jews, so was baptism the primary identity marker for Christians. The Jews were God’s old covenant people, whereas the church was God’s new covenant people. For Zwingli, baptism was “a covenantal sign that does not in itself or as an act impart or even strengthen faith. Zwingli rejected what he saw as the pernicious Anabaptist argument that baptism was a pledge to live a sinless life, a position he claimed was a new form of legalism to bind the conscience. It would make God a liar, as such lives were not possible. ” (Gordon, p. 126-127).

Zwingli acknowledged that the New Testament nowhere explicitly mentions that infants were to be baptized. However, to use that as an argument against infant baptism was no different than saying that women could be denied the Lord’s Supper, since there were evidently no women present when Jesus celebrated the Last Supper with his male disciples (Gordon, p. 127)

“Baptism is the rite of initiation into the covenant of Christ, as circumcision was for the Israelites. Circumcision did not bring faith: it was a covenantal sign that those who trust in God will raise their children to know and love God. Instruction follows initiation, so children are baptized and then are taught the faith. Baptism cannot save, but it is a sign or pledge of the covenant God has made with humanity. It was instituted by Christ for all” (Gordon, p. 127).

On the other side, Zwingli continued to receive serious pushback from the Roman Catholic papal authorities, who viewed Zwingli as much of a dangerous rebel as were the Anabaptists. Zwingli got on the theological radar of Johann Eck, one of Martin Luther’s fiercest theological opponents. For Eck, Zwingli was infected with the same mind virus as Luther. Eck cited Paul’s letter to Titus in reference to Zwingli: ‘After a first and second admonition, have nothing more to do with anyone who causes divisions, since you know that such a person is perverted and sinful, being self-condemned’ (Titus 3:10–11; Gordon, p. 123).

Zwingli’s outspoken views eventually would lead to a crisis, which ended poorly with him and his family. In the next part of this two part look at Zwingli’s life, we will consider the last few years of the Protestant reformer of Zurich.

In the meantime, enjoy this video interview with the author of Zwingli: God’s Armed Prophet , Bruce Gordon, as he talks about his book: