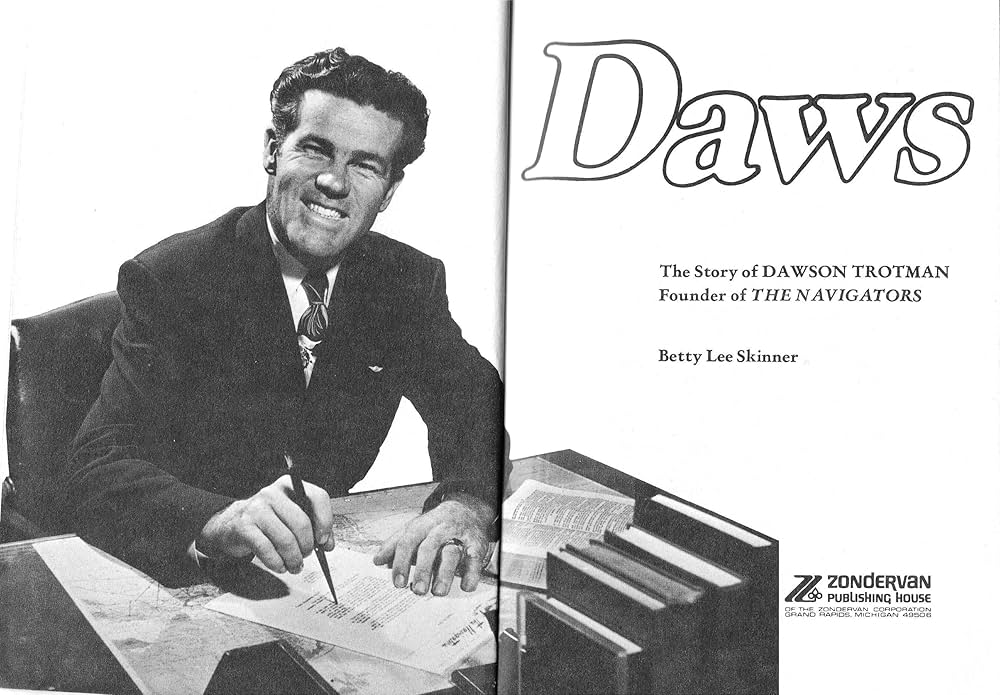

Dawson Trotman (1906-1956) was the founder of the Navigators, one of the most influential evangelical missionary movements begun in the mid-20th century. Daws: The Story of Dawson Trotman, Founder of the The Navigators, written by Betty Lee Skinner in 1974, tells the story of this man who interacted with some of the leading figures of American evangelical Christianity of the 20th century.

Skinner, who had worked in communications with the Navigators ministry for years, died in 2013, about a year after I started to read this book. My wife and I had decided to visit friends in Colorado, but we took a few days to visit Glen Eyrie, the home of the Navigators, known for its famous castle built by the founder of the city of Colorado Springs, William Jackson Palmer, nestled in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, next to the Garden of the Gods city park. We arrived at Glen Eyrie less than two weeks after the 2012 Waldo Canyon Fire had devastated several neighborhoods surrounding Colorado Springs. I climbed a ridge at the edge of the Glen Eyrie property and looked over to see hundreds of homes that had been completely wiped out by the fire, which came almost within a mile from the Glen Eyrie property.

It was an eerie setting to begin reading Daws. There was this sense that God protected Glen Eyrie from the fire in much the same way God protected and helped the ministry of the Navigators to flourish in those early years led by the energetic and single-minded Dawson Trotman.

Betty Lee Skinner’s Daws is an inspiring read, about the man who gave the evangelical world great tools for discipleship, like the Wheel Illustration, the Bridge Illustration, and Word Hand Illustration, and the Big Dipper. That man was Dawson Trotman.

Daws tells a remarkable story, but the book at just under 400 pages in fairly tight print, is pretty long, which explains why it took me so long to finish the book. Skinner peppers the text with so many names that it is difficult to keep track of who is who (How did Skinner, a close associate with Trotman, keep such detailed records?). All the minutia was a bit too much “TMI” for me (“Too Much Information”). Some twelve years later, I finally made it all the way through the book. For a quicker read, I would recommend Robert D. Foster’s The Navigator for a shorter survey of the life of this remarkable man. But I wanted to tackle Daws to get an in-depth feel for what made this man, Dawson Trotman, tick. Skinner’s attention to detail shows that Dawson Trotman was an amazing human being.

Dawson Trotman grew up in Southern California, becoming a fine athlete, the valedictorian of his high school, and the student body president. But after high school, Trotman floundered. He worked in a lumberyard, where he developed a penchant for gambling, learned how to be a pool shark at the billiard table, and got drunk with his friends more than once.

He had not grown up in much of a Christian family, only going to church every now and then, mostly spurred on by the influence of his mother, but not his father. Yet his church going did not seem to keep his behavior in line. Even in high school, he had been stealing regularly from the school’s locker fund. He felt terribly guilty about what he had done, but he felt like there was nothing he could do about it.

After high school, after one night of getting drunk and picked up by the police, Dawson slipped away from his friends to attend a church meeting at a nearby Presbyterian church where there was a Scripture memory contest. There he promised to memorize ten Bible verses. He came back to the meeting the following week and he was the only guy who managed to memorize all ten verses.

One of the verses was John 1:12, which he had memorized in the King James Version: “But as many as received him, to them gave the power to become the sons of God, even to them that believe on his name.” While walking on his way to work one day, that verse came to mind. It was like the Apostle’s Paul “road to Damascus” experience or Saint Augustine of Hippo’s “tolle lege” moment, “take up and read.” By the time he made it to the lumberyard for his shift, his life trajectory had been set.

Within a few years, Trotman had taken a Bible class taught by legendary evangelist Charles E. Fuller, the future founder of Fuller Theological Seminary, on the Book of Romans and Ephesians. He wanted to give his whole life to full-time Christian work. Trotman developed this principle of learning to find simply one other man he could pour his life into, who could then go on to find another man who could do the same, based on 2 Timothy 2:2.

Scripture memorization was at the heart of such one-on-one encounters. He had the greatest early success working with Navy sailors aboard the U.S.S. West Virginia. He married a woman he had known from high school who was also a Christian, Lila. They began Bible studies for Navy servicemen in their home. This was how the Navigators ministry was born.

It was a pivotal time between the two world wars. By the time the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in 1841, the Navigators were multiplying all across the Navy, and the Navigator ministry was spreading out among businessmen, nurses, and other groups. The U.S.S. West Virginia was one of first ships attacked at Pearl Harbor, and the Navigator men of that ship were dispersed across other ships in the Navy, inspired by Trotman’s example, replicating this multiplication method of disciple-making taught by Trotman.

Over those decades and even after World War 2, Trotman and other Navigator disciples developed various tools for training men to learn to follow Jesus. The “Wheel illustration” placed the life of “the obedient Christian in action” on the rim of the wheel, with Christ at the center hub, with four spokes supporting the wheel: Prayer, the Word, Witnessing, and “Living the Life” (or Fellowship with other believers). Each component of the wheel had a Bible verse or set of verses to be memorized to go along with the illustration.

The “Bridge illustration” showed a great chasm between two cliff edges. On one cliff edge was the “wages of sin is death” (Romans 6:23) and on the other cliff edge was “eternal life” in Christ. The cross of Jesus was placed across the chasm, thereby enabling a person to cross the bridge from death to life. The “Hand illustration” showed a hand grasping the Bible, where each finger represents a principle: the little finger (hearing), the ring finger (reading), the middle finger (studying), the index finger (memorizing), and the thumb (meditation). Many like myself continue to use these tools today.

Reading Daws gives you the story of how these various discipleship principles and illustrations were spread out and copied across divergent Christian ministries of the 20th century. Evangelist Billy Graham met Trotman and began to use these Navigator principles for follow-up in his crusade meetings. While driving out to California, a young Bill Bright picked up a hitch-hiker, who invited Bright, who was not yet a Christian, to spend his first night at the Navigator home of the Trotmans. Bill Bright would eventually become the founder of Campus Crusade for Christ, now called “CRU.” Jim Rayburn, the founder of Young Life, became best friends with Dawson Trotman. Henrietta Mears, the highly influential Sunday School leader at Hollywood Presbyterian Church, mentored Trotman. Wycliffe Bible Translators’ Cam Townsend invited Trotman to train his staff in Scripture memory principles. Reading Daws for me was like going through a survey of “Who’s Who” in American 20th century evangelicalism, so wide was the reach of Dawson Trotman.

Dawson Trotman was a man with a singular focus and vision in life. This virtue enabled him to chart a life course and principles which continues to indirectly impact countless people well over a half century later. Yet it is also a characteristic which has not always appealed to others. He was highly disciplined, a quality that served well in the Navigator outreach to Navy personnel. But Daws would publicly call out men who had not memorized their verses at meetings, which spurred some to work harder at it, while alienating others. There is no doubt: Daws was an extroverted perfectionist.

For decades after his death, the personality of Daws could still be felt. When the Navigators tried to extend their outreach towards college students, the regimentation expected did not always suit the college environment that well, and by the late 1980s, the college ministry efforts of the Navigators began to shrink. In my college years, my friends often joked that the Navigators were more rightly called the “Never-Daters,” as they tended to encourage sharper lines in terms of male and female interactions in their ministry efforts. Unlike other ministries like Young Life, CRU, and InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, which all target specific age groups and different communities, the Navigators have tended to ebb and flow in their efforts to target specific communities.

But what Navigators has done and continues to do best, as set forward by Dawson Trotman’s example, is map out an effective strategy for one-on-one Christian disciple making, no matter what the cultural and community context. Many Christians I have known for years take small note cards or sticky-notes, writing out Scripture verses on them, placing them on kitchen refrigerators, bathroom sinks, and car dashboards, to help with Scripture memorization, an idea taken from the Navigators Topical Memory System, which Dawson Trotman helped to pioneer. The Bridge illustration for sharing one’s faith with another person is an enduring classic still drawn out on paper napkins in coffee houses and restaurants somewhere in the world every day.

The story which Skinner tells about the acquisition of the Glen Eyrie property, for use as the Navigators headquarters, is inspiring on its own. Trotman was absolutely convinced that God wanted the Navigators to have Glen Eyrie, but there was no money for it when the acquisition was first proposed. Setback after setback continually arose in the months prior to the deadline for the sale. Yet at different stages of the process, money would come in just in the nick of time. Disaster loomed just near the closure of the deal, as the entire sum of the money that was raised was accidentally wired to the wrong bank, and the mistake was not uncovered until after the bank had closed for the day. But the owner of the bank was also a Navigators donor, and so he reopened the bank, enabling Trotman to finalize the sale in the last few hours. Trotman’s journey of faith was filled with suspense!!

In 1956, Dawson Trotman was a speaker at Jack Wyrtzen’s Word of Life camp at Schroon Lake, in upstate New York. Four days earlier, Trotman had given his last message to Navigator staff at Glen Eyrie on the Big Dipper illustration, summarizing all of the components of effective Navigator discipleship.

That afternoon at the Word of Life camp, Jack Wyrtzen took Trotman and a few campers on a boat ride to do some water skiing. At one moment, the boat hit some choppy water, throwing both Trotman and a young female camper into the water. Trotman did his best to save the life of this young woman by holding her up to keep her from drowning, which he did. However, after years of driving a hard schedule, Dawson Trotman was mentally and physically exhausted. So in the process of trying to save the other camper, who apparently did not know how to swim, Trotman himself drowned, thus ending the life of one of American evangelicalism’s most influential leaders. At his memorial service held at Glen Eyrie, Billy Graham stated that “Daws died the same way he lived—holding others up.”

Daws is also an examination of a much different spiritual climate during the early to mid 20th century. Soul-winning and discipleship making based on Scripture memorization made sense to an American society which was culturally Christian. But Daws rarely, if ever, discusses Christian apologetics, which is now so central to evangelistic work in the 21st century, when so many people have questions about the trustworthiness and clarity of the Bible. The early Navigators work simply assumed that most people they worked with believed the Bible to be true and straight-forwardly interpreted. Trotman never had to deal with the confusion of truth promoted by our current age of social media.

The challenge for discipling people back then among the Navigators was in the realm of application. Today, the cultural climate is a lot more skeptical about the truthfulness of the Christian faith, a step that needs to be addressed before you even get to the application of what the Bible teaches. Furthermore, young people today are looking for authenticity and trustworthiness, in an age when Christians are often viewed with some degree of suspicion. Technology can be both an aid to discipleship, as well as being a distraction undermining discipleship.

In other words, here in the 21st century we simply can not assume that drawing “The Bridge” illustration on a paper napkin while having lunch with an inquiring friend will be enough to woo a non-believer to pursue having a relationship with Jesus. Those days of assuming a biblically literate culture that Dawson Trotman worked in no longer make sense in a pluralistic society which is suspicious of the moral and metaphysical claims of the Christian faith. Human brokenness compound the problem, where many today live lives of isolation and loneliness to a greater degree than in Dawson Trotman’s day. Daws gave us some basic tools to work with, but nearly a century later we need to tweak and refine some of the those tools in order to sensibly connect with people who desperately need to know the Good News of Jesus.

The Navigators today are still a flourishing ministry, though a look at their website can tell you that there is no specific target cultural group or community that the Navigators are trying to reach. The vision is still all about one-on-one discipleship, equipping disciples with tools like Scripture memory, which is the core DNA of what made Dawson Trotman tick.

While Betty Lee Skinner’s Daws is on the rather long side, her book gives interested readers a studied look into the life of one of the great Christian leaders of the 20th century, whose influence continues on into the 21st century.

The follow videos explain several of the most helpful illustrations developed by Dawson Trotman and the early Navigators ministry.

July 24th, 2025 at 7:59 pm

Thank you for posting this summary of the book, and of Dawson Trotman’s life. My dad was scheduled to drive to Glyn Eyrie in 1958, considering a life of ministry under the Navigator banner. A snowstorm providentially prevented that trip, and he ended up pastoring and church planting for 60 years as a Southern Baptist. But the early influence the Navigators had on him was always made plain to me as I grew up, and I have a great appreciation for Dawson Trotman, mediated through the next generation of disciple-makers (Billy Hanks Jr, Howard Hendricks, Robert Coleman, Leroy Eims, etc.).

LikeLike