Elisabeth Elliot was widowed now for a second time. Elisabeth Elliot was forty-six years old when her husband, sixty-four year old Addison Leitch died after a nearly year long difficult battle with cancer.

Almost exactly half of her life was over, with another half remaining by 1977. Going through another period of grief reinforced the reality of suffering, a theme which recurred several times in her extensive writing career. This last period of Elisabeth Elliot’s life catapulted her even further into the public eye, with her advice directed mainly towards women through her radio program “Gateway to Joy,” and more books. Yet it is arguably the most controversial period of her life as well.

Here in this final blog post reviewing several biographies of the life of the iconic 20th-century missionary and author, Elisabeth Elliot (previous blog posts here and here), we examine this last period of her life as told by her biographers.

Elisabeth Elliot’s Mid-Life Crisis

Towards the end of Addison Leitch’s life, Elisabeth began to take on boarders in her home, initially to assist her as she nursed her husband in his final days. Little did she know then that two of these boarders would eventually occupy major roles in her life.

Walter Shephard was a son of missionary parents serving in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Upon returning to the United States, Walter Shephard as a young adult lived a prodigal life, quite far away from the Christian life modeled by his devout parents. A near deadly car accident got his attention and he eventually gave his life over to Christ. He ended up at Gordon-Conwell Seminary, and took a room in Elisabeth Elliot’s home. He got along extraordinarily well with Elisabeth Elliot, but he soon developed a close friendship with young Valerie, Elisabeth Elliot’s daughter, when she was home from college one semester. The two were married shortly after Valerie graduated from Wheaton College.

Lars Gren was in many ways quite far apart from Walter Shephard. A former salesman who in mid-life decided to go to seminary to become a hospital chaplain, Lars Gren never knew anything about Elisabeth’s fame as the wife of the martyred missionary, Jim Elliot, until after he became a boarder in Elisabeth Elliot’s home. Unlike Walter Shephard, Lars was not a great conversationalist. He did not have the most exciting personality. But what he did have was a sense of faithfulness and loyalty to Elisabeth, having a strong desire to please her, and he seemed always available. He was always there.

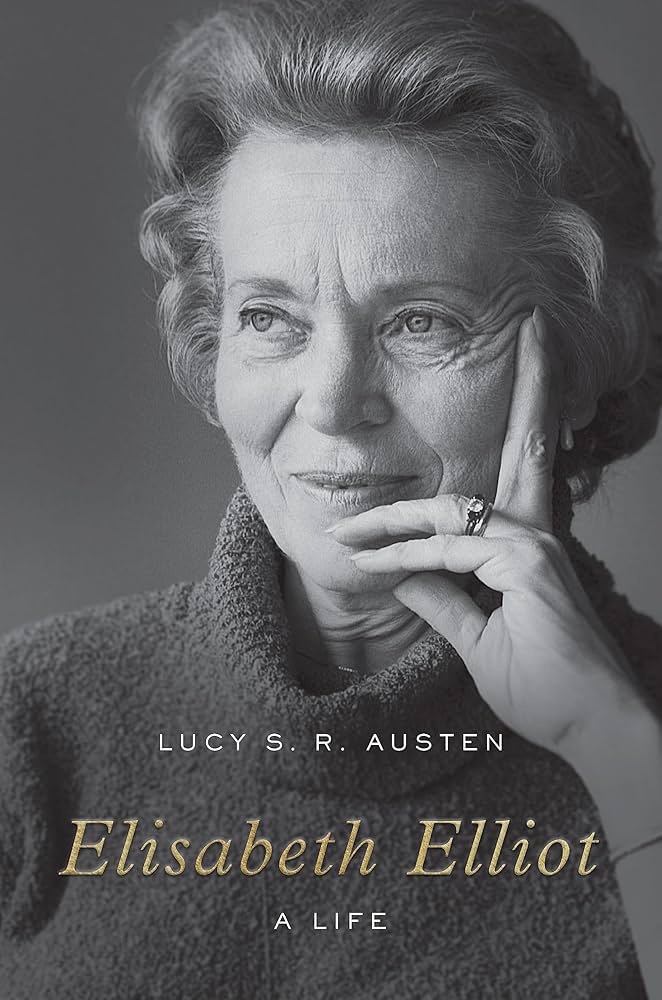

Lucy Austen’s Elisabeth Elliot: A Life, a one-volume biography of Elisabeth Elliot’s life. Along with Ellen Vaughn’s two volume work about Elisabeth Elliot, both authors have some surprises towards the end their work about Elisabeth’s third marriage to Lars Gren.

Marriage Number Three: Lars Gren

According to Lucy Austen, Elisabeth’s theological views had more or less fully matured by the time she married Lars Gren in 1977. She was a survivor of two marriages, both ending in the deaths of her then spouse. Her career as an author and a speaker was well established, traveling frequently for speaking engagements. She constantly received invitations to travel for speaking opportunities all over the world. Her career was at its zenith.1

Lars Gren was gifted in ways that Elisabeth was not when it came to supporting Elisabeth’s work as a speaker and a writer. Elisabeth had a difficult time working with an agent, where balls were oftened dropped much to Elisabeth’s frustration. But Lars was able to handle many of Elisabeth’s affairs, including setting up a book table at Elisabeth’s speaking events and selling many of her books. As a business partner in supporting Elisabeth’s career, Lars looked like a perfect match. Perhaps there was more to Lars Gren than simply a suitable business partner?

At first, Elisabeth had completely ruled out yet a third marriage. But she missed the male companionship she enjoyed when she was married. She wondered what would be harder, remaining single, or marrying Lars. In her way of discerning God’s will, she reasoned that given two fairly even choices, it was better to choose the more difficult path. The problem was that Elisabeth was not entirely sure which path would be harder than the other.

At the peak of her life as a speaker and author, she became concerned that she might be too dismissive of Lars, as marrying a kind of “nobody” like Lars might spoil her reputation. Lars was neither an intellectual nor a terribly social person as Elisabeth Elliot had become. It was a spiritual problem she reasoned. Was she having too much of a secular mindset, thinking too much about how others thought of her?2

Yet eventually, she was slowly won over to Lars’ initiative in moving forward in their relationship, and eventually the two became married. Lars told Elisabeth that he wanted to protect her, to build a fence around her. That sense of security that Lars promised struck a chord with Elisabeth.

Prior to the marriage, Elisabeth was the one in authority as Lars lived in her home as a boarder, and he recognized her authority as the owner of the home. As a strong-willed woman, Elisabeth Elliot aspired to follow her own advice to other women, by encouraging Lars to lead in the relationship when it became apparent that Lars had a more intimate interest in her. Both Elisabeth and Lars agreed that the husband was to be in charge in a marriage. However, early on she realized that Lars’ expression of being a husband in charge had obscured serious control issues in his personality.

Elisabeth Elliot and Lars Gren were married in 1975, and remained married until her death 2015. Lars Gren was diagnosed with dementia about a year later, and currently lives in a memory unit in a retirement facility. Elisabeth’s marriage to Lars has been subject to historical controversy.

The Dark Side of Elisabeth’s Marriage to Lars Gren

Was the Lars Gren Elisabeth knew before their marriage different from the Lars Gren she came to know after getting married? Based on Elisabeth’s journals and other sources, Lucy Austen reports that Lars’ pattern was to express anger over losing control, then followed by an action to reassert that control.

If Lars perceived a situation where he was losing control, in a public setting, or some other situation where he could not express his frustration, he would typically wait until he was privately with Elisabeth before expressing his anger, always followed by an action to reassert his control. This pattern was repeated over, and over, and over again (Austen, chapter 31).

Elisabeth picked up on this pattern first on their wedding day. When the couple were leaving the sanctuary, after a jubilant ceremony among friends and family, a decision had to be made as to which way to go as the couple walked together. Lars started to walk one direction while Elisabeth steered him to walk the other way, creating some confusion, and generating some chuckles from the wedding guests.

Yet when the couple returned to their home to pick up their luggage to go on their honeymoon, Lars announced that he was not ready, and they would not leave until he “was good and ready.” Lars instructed Elisabeth to contact the housesitter they had lined up to wait to come over until Lars was ready to leave, not because he had something else to do, but as a way of reasserting control. Elisabeth embarrassingly contacted the housesitter about the change in plans, and it was apparently several hours later before the couple finally left to go on their honeymoon night to a place in Boston (Austen, chapter 31).3

Later in the marriage, Lars would control Elisabeth’s schedule, dictating to her when she could accept invitations to go out for tea with a friend. He would check on the car’s odometer whenever Elisabeth came back from driving somewhere. Sometimes, the outbursts of anger from Lars surprised her, such that it was not always clear to her what she had done to trigger Lars’ sense of losing control.

After a while, Elisabeth was suffering the effects of “this destructive behavior” by Lars. Friends began to notice that Elisabeth went to great lengths to hide small mistakes from Lars, as when she would take wrong turns while driving, for instance. Despite the fact that these were all signs of abusive behavior from Lars, the situation was complicated as there were some genuinely good things going on with their marriage as well. Elisabeth was still appreciative of the strengths Lars possessed which she herself lacked (Austen, chapter 32).

Elisabeth told a few friends that when Lars refused to leave to go on their honeymoon until he “was good and ready,” she had made a “mistake” there on her wedding day. However, “she no longer believed her mistakes could interfere with the sovereignty of God, or the fulfillment of God’s promise to bring the best possible good out of the events of her life, whatever they were” (Austen, chapter 32). Elisabeth Elliot sought to trust everything to God, even in her suffering, without pretending that suffering was somehow good. Elisabeth believed that “suffering [can be] transfigured into a means of joy if we accept it, give thanks in it, and offer it back to God” (Austen, chapter 32).

Joshua Harris’ I Kissed Dating Goodbye, the out-of-print book which defined purity culture in the 1990s.

Purity Culture?

Behind Through Gates of Splendor, Elisabeth Elliot’s perhaps most popular book, Passion and Purity: Learning to Bring Your Love Life Under Christ’s Control, first published in 1984, became an early standard bearer title for the “purity culture” movement of the 1990s, which emphasized sexual purity before marriage. However, as Lucy Austen notes, her 1996 book, Quest for Love: True Stories of Passion and Purity, offered a more balanced perspective on the “purity culture” movement, though Quest for Love was not as popularly received as Passion and Purity was. The latter book, Quest for Love, emphasized that sexual purity in the physical sense was important, but so was emotional purity. The first concern a Christian should have is not in trying to find a mate, but rather in learning to seek wholeheartedly after God and trusting in God in all things (Austen, chapter 33).

Advocates of “purity culture” sought to emphasize courtship as the most the biblically faithful way of finding the right Christian mate. Dating was looked down upon, as dating was seen as opening a door to physical and emotional intimacy, in ways that could lead to damage later in marriage. Instead, young people were encouraged to take on a purity pledge, promising abstinence from sex before marriage. Opponents of “purity culture” have seen it differently, as such opponents have viewed “purity culture” itself as leading to damage, resulting in needless anxiety, particularly among women, and even resulting in failed marriages. Others have said that “purity culture” put too much emphasis on moralism and the body, and not enough emphasis on truly glorifying and magnifying Christ.

Nevertheless, despite all of the nuance, Elisabeth Elliot’s name became synonymous with attitudes behind the “purity culture” movement. Josh Harris, the author of I Kissed Dating Goodbye, thought to be the book of the 1990s which defined “purity culture,” even wrote a forward to a 2013 reprint edition of Passion and Purity. Less than ten years later, Harris would ask the publisher to stop printing copies of I Kissed Dating Goodbye, renouncing his role in the “Purity Culture” movement, and even announcing his own deconversion from Christian faith.

Virginia Ramey Mollenkott (1932-2020), a fellow schoolmate of Elisabeth Elliot’s at Hampden DuBose Academy in Florida, where Elisabeth attended high school, was a fellow author who assisted Elisabeth Elliot with some of her writing projects. Mollenkott would eventually become an outspoken LGBTQ advocate, calling for changes to sexual ethics among evangelical Christians. Elisabeth Elliot became an outspoken critic of her school friend’s views.

Elisabeth Elliot: Her Struggles With Gender and Sexuality

Elisabeth’s views of gender and sexuality have been the most controversial aspects of her legacy, so it is worth looking at these in some detail. Elisabeth Elliot did engage in a series of letters with her mother, Katharine, concerning a good friend of Katharine’s who was experiencing same-sex sexual attraction, presumably a fellow Christian. Elisabeth encouraged her mother, Katharine, to look for the visible fruits of the spirit in this person’s life, and focus on the characteristics of love that Katherine’s friend was living out. Elisabeth encouraged her mother to accept this person, to trust God, and to understand that someone’s experience of same-sex attraction was not outside one’s obedience to God. From a letter Elisabeth wrote:

To hope for victory over such a thing is like hoping for victory over blindness or paralysis. I believe God could do it. He could have given dad two eyes again, but the problem is far more complex than a simple matter of sin. It is not sin in any sense of the word, though it is a frame of mind, an attitude which presents its own particular kind of temptation. Sin only enters when the law of love is transgressed, if I understand Jesus’ interpretation of the Law (from Austen, chapter 27).

Elisabeth went on to remind her mother of the deep friendship between David and Jonathan, as evidenced in 1 Samuel 20:41 and 2 Samuel 1:26. Elisabeth was encouraging her mother to be honest with what the Bible says, not ignoring or explaining away what we find in Scripture. Elisabeth sought to uphold the primacy of love in the life of the Christian. Elisabeth had a growing sense of frustration with American evangelicalism’s focus on things one ought not to do, like drinking alcohol or going to movies, while ignoring less trivial and clearer cut wrongs like lying and idolatry (Austen, chapter 27).

Based on this correspondence she had with her mother, Elisabeth Elliot’s views on homosexuality appear to coincide with what some call “Side-B” views regarding same-sex attraction. She was able to uphold a traditional Christian sexual ethic regarding marriage as being between one man and one woman, while at the same time acknowledging that same-sex attraction is not inherently sinful in and of itself. Same-sex attraction only becomes sinful when acted upon, either in terms of lust or actual physical behavior. It would appear that Elisabeth Elliot’s “third-way” approach to human sexuality might not be accepted in certain conservative quarters of evangelicalism today.

Interestingly, the question of how to deal with homosexuality as a Christian was never that far away from Elisabeth Elliot. Austen reports that one of the editors Elisabeth consulted for the manuscript revisions for No Graven Image was none other than Virginia Ramey Mollenkott, a former schoolmate friend and English scholar, who would later become a prominent feminist theologian and advocate for gay marriage in the evangelical church. Before making her views on homosexuality public, and entering a same-sex partnership herself, Mollenkott had served as an English stylist consultant for the New International Version translation of the Bible, back in the 1970s.

In 1978, Mollenkott co-authored Is the Homosexual My Neighbor?: A Positive Christian View, with Letha Dawson Scanzoni. In subsequent editions, particularly in the 1994 edition, this Mollenkott/Scanzoni book would eventually become one of the first books advocating gay marriage, targeting a conservative evangelical Christian audience. Mollenkott died in 2020.

Letha Dawson Scanzoni (1935-2024) partnered together as an author with Virginia Ramey Mollenkott to write a book Is the Homosexual Thy Neighbor?, which over subsequent editions, increasingly called for LGBTQ advocacy. Scanzoni also co-wrote a book with Nancy Hardesty, All We’re Meant to Be, advocating for”biblical feminism,” which today in its more conservative form is typically known as “evangelical egalitarianism.” Scanzoni maintained a regular correspondence with Elisabeth Elliot, until the conflicting views between the two became ultimately unreconcilable.

Elisabeth Elliot’s Unwanted Quarrel with Evangelical Egalitarianism

Letha Dawson Scanzoni, being another author like Elliot, struck up a lengthy correspondence with Elisabeth Elliot, which lasted for several years. Scanzoni was evidently a great fan of Elisabeth Elliot’s work, but was curious to know what Elliot’s views were on “Christian feminism.” The Scanzoni-Elliot relationship eventually diverged as the two women disagreed with one another deeply theologically.

Scanzoni at one point teamed up with another author, Nancy Hardesty, to write the 1974 book All We’re Meant to Be: A Biblical Approach to Women’s Liberation. While Scanzoni was a graduate of Moody Bible Institute, Nancy Hardesty was a graduate of Elisabeth Elliot’s alma mater, Wheaton College. All We’re Meant to Be, which came out in multiple editions, was one of the first attempts to provide evangelicals a different framework for interpreting difficult passages regarding the role of women in marriage and in the church. This book stayed away from the more controversial questions regarding gender and sexuality, predating contemporary discussions about same-sex marriage and transgender identity.

Elisabeth also attended conferences, where Scanzoni and Hardesty were highlighted as speakers. In particular, Elisabeth Elliot regarded Hardesty’s theology as “blasphemous” and a conference featuring Hardesty as “nauseous” (Austen, chapter 31). For Elisabeth, the concepts of “Christian” and “feminist” were utterly incompatible. Elisabeth believed in a hierarchical relationship between husband and wife, the husband being the head. She also extended this view by arguing against the ordination of women.

Elisabeth’s “go-to” Bible passage for refuting Scanzoni and Hardesty was 1 Corinthians 11:9:

Neither was man created for woman, but woman for man (ESV).

To the arguments by Scanzoni and Hardesty, Elisabeth Elliot responded that the Apostle Paul taught that a wife is created to submit to her husband. To clarify, this is a command given to the wife, and not to the husband. The husband is not to enforce anything on his wife. Rather, it is the responsibility of the wife to take upon herself this submissive obedience to the husband. Anything outside of this principle is an act of disobedience to the clear teaching of Scripture. It is up to the woman to adjust to the man, not the other way around (Austen, chapter 30). The same reasoning was then applied as an argument against the ordination of women, following the Apostle Paul’s instructions in 1 Timothy and Titus, which Elisabeth Elliot understood to restrict the office of local church elder to qualified men only.

Some find it ironic that while she opposed the idea of having women serve in pastoral teaching positions, she herself spoke to mixed-audiences including men. While being a vocal critic of feminism more generally, it was the early feminist movement that made it possible for Elisabeth to attend college, enabling her to have a career as an author. It is not entirely clear how Elisabeth Elliot would try to resolve these apparent contradictions.

While much of the above material about Elisabeth Elliot’s views on the complementarian/egalitarian issue is gained from Lucy Austen’s Elisabeth Elliot, A Life, it would be important to highlight what Ellen Vaughn says about the issue, particularly from her second biographical volume, Being Elisabeth Elliot. Vaughn does not comment much about Elisabeth’s specific views, aside from saying that Elisabeth Elliot believed that God did indeed create women to be in an inferior position relative to men, according to what is taught in Genesis. Masculinity and femininity were the issues at hand, not merely biological distinctions between male and female. This was all a part of God’s design for humanity in “graduated splendor” (Vaughn, Being Elisabeth Elliot, chapter 34). Those who do reject God’s design for marriage show signs of rebellion against authority more broadly.

But what Vaughn does comment more on is on Elisabeth’s self-conscious role on using her platform as a leading evangelical speaker and author among women to speak against a view of male/female relations which went against the created order of reality, and the full tone and arc of Holy Scripture. She did not speak out because she viewed herself as God’s appointed spokesperson, someone having an inflated ego. Instead, she was quite self-conscious of her own inadequacies and her own failures. Challenging the feminists and egalitarians of her day was not something she relished. Rather, it was simply a matter of speaking the truth and opposing error, even though it was painful and did not win her friends among those who disagreed with her.

In opposing Christian “biblical feminism,” or what is known today as “evangelical egalitarianism,” she had felt the same way when she challenged leaders in the evangelical missionary subculture, which she criticized for inflating numbers of converts in the mission field in order to try to demonstrate positive results as a public relations move. She felt sidelined by the evangelical public when promised speaking engagements were canceled because she was “telling the truth” about what was really going on in overseas mission fields. It hurt her when Christian bookstores banned her novel, No Graven Image, and otherwise boycotted her books because she insisted on being a truth-teller instead of always towing the party line.

According to Ellen Vaughn, Elisabeth Elliot expected opposition when it came to telling the truth. Sometimes, her determination to follow what she believed to be the truth cost her in terms of creating conflict that was not always necessary.

Elisabeth felt compelled to speak out on the “woman question” even though she had no desire herself to read or hear about the issue. She did not want to “stick her neck out” again because she took an unpopular stand on a very public issue. She did not want to be pitted against Mollenkott, Scanzoni, Hardesty, or other evangelical egalitarians who opposed her traditionalist views. Nevertheless, she viewed the evangelical egalitarian movement as marking a drifting away from core biblical teachings, and that speaking out against it was a must. She did not want to be crossed off with a “there she goes again” type of sentiment against her. Rather, she viewed her opposition to evangelical egalitarianism as an act of obedience to a holy God (Vaughn, Being Elisabeth Elliot, chapter 34).

C.S. Lewis. became an inspiration for Elisabeth Elliot in developed her views regarding the relationship between men and women in the home and in the church, though the two were not perfectly aligned with one another.

C.S. Lewis and Elisabeth Elliot’s Views on Egalitarianism

Elisabeth Elliot appealed to the writings of C.S. Lewis for support of her thinking, particularly from this quote found in “Membership,” from Lewis’ book The Weight of Glory (Austen, Chapter 31):

“I do not believe that God created an egalitarian world. I believe the authority of parent over child, husband over wife, learned over simple to have been as much a part of the original plan as the authority of man over beast.”

However, Elisabeth does not appear to support the other side of Lewis’ thinking, which suggests that the fiction of egalitarianism is necessary in order to prevent the abuse of God’s plan distorted by the Fall of humankind. From Lewis’ essay “Equality” in his book Present Concerns, this quote in full contextualizes Lewis’ thinking:

“A great deal of democratic enthusiasm descends from the ideas of people like Rousseau, who believed in democracy because they thought mankind so wise and good that everyone deserved a share in the government. The danger of defending democracy on those grounds is that they’re not true. And whenever their weakness is exposed, the people who prefer tyranny make capital out of the exposure. I find that they’re not true without looking further than myself. I don’t deserve a share in governing a hen-roost, much less a nation. Nor do most people—all the people who believe advertisements, and think in catchwords and spread rumours. The real reason for democracy is just the reverse. Mankind is so fallen that no man can be trusted with unchecked power over his fellows. Aristotle said that some people were only fit to be slaves. I do not contradict him. But I reject slavery because I see no men fit to be masters.

“This introduces a view of equality rather different from that in which we have been trained. I do not think that equality is one of those things (like wisdom or happiness) which are good simply in themselves and for their own sakes. I think it is in the same class as medicine, which is good because we are ill, or clothes which are good because we are no longer innocent, I don’t think the old authority in kings, priests, husbands, or fathers, and the old obedience in subjects, laymen, wives, and sons, was in itself a degrading or evil thing at all. I think it was intrinsically as good and beautiful as the nakedness of Adam and Eve. It was rightly taken away because men became bad and abused it. . . .

“But medicine is not good. There is no spiritual sustenance in flat equality. It is a dim recognition of this fact which makes much of our political propaganda sound so thin. We are trying to be enraptured by something which is merely the negative condition of the good life. And that is why the imagination of people is so easily captured by appeals to the craving for inequality, whether in a romantic form of films about loyal courtiers or in the brutal form of Nazi ideology. The tempter always works on some real weakness in our own system of values: offers food to some need which we have starved.

“When equality is treated not as a medicine or a safety-gadget but as an ideal we begin to breed that stunted and envious sort of mind which hates all superiority. That mind is the special disease of democracy, as cruelty and servility are the special diseases of privileged societies. It will kill us all if it grows unchecked.”

Back to Lewis’ “Membership” essay, Lewis has this to say regarding a balance between complementarian and egalitarian ways of thinking. Again, quoting this in full contextualizes Lewis’ perspective:

“I believe in political equality. But there are two opposite reasons for being a democrat. You may think all men so good that they deserve a share in the government of the commonwealth, and so wise that the commonwealth needs their advice. That is, in my opinion, the false, romantic doctrine of democracy. On the other hand, you may believe fallen men to be so wicked that not one of them can be trusted with any irresponsible power over his fellows….

I believe that if we had not fallen, Filmer would be right, and patriarchal monarchy would be the sole lawful government. But since we have learned sin, we have found, as Lord Acton says, that “all power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” The only remedy has been to take away the powers and substitute a legal fiction of equality. The authority of father and husband has been rightly abolished on the legal plane, not because this authority is in itself bad (on the contrary, it is, I hold, divine in origin), but because fathers and husbands are bad. Theocracy has been rightly abolished not because it is bad that learned priests should govern ignorant laymen, but because priests are wicked men like the rest of us. Even the authority of man over beast has had to be interfered with because it is constantly abused. . . .

“Do not misunderstand me. I am not in the least belittling the value of this egalitarian fiction which is our only defence against one another’s cruelty. I should view with the strongest disapproval any proposal to abolish manhood suffrage, or the Married Women’s Property Act. But the function of equality is purely protective. It is medicine, not food. By treating human person (in judicious defiance of the observed facts) as if they were all the same kind of thing, we avoid innumerable evils. But it is not on this that we were made to live. It is idle to say that men are of equal value. If value is taken in a worldly sense—if we mean that all men are equally useful or beautiful or good or entertaining—then it is nonsense. If it means that all are of equal value as immortal souls, then I think it conceals a dangerous error.”

Lewis was an intellectual role model for Elisabeth Elliot. C.S. Lewis and Elisabeth Elliot held mutually appreciating views about marriage, women’s ordination to the presbyteriate or the office of “elder” (the answer being “NO” for both thinkers), and God’s created design for men and woman more broadly. Nevertheless, they also clearly differed on certain fundamental details.

Elisabeth Elliot and Today’s Complementarian Versus Egalitarian Debate

Nancy Hardesty died in 2011, several years before Elisabeth’s death. Virginia Mollenkott dies in 2020. Letha Scanzoni died earlier this year, in 2024. A generation of female thinkers have passed the baton along to a new, younger generation, where the debates continue.

The fact that Mollenkott, Scanzoni, and Hardesty had such close interactions with Elisabeth Elliot highlights the tensions evangelicals have had in the complementarian and egalitarian discussion since the 1970s. Mollenkott, Scanzoni, and Hardesty were both influential in the formation of the Evangelical Women’s Caucus in 1974, which initially began as a group promoting “biblical feminism” and promoting the ordination of women. The group eventually had a split, the more liberal group promoting gay marriage and other elements of LGBTQ advocacy, which is now called Christian Feminism Today. The more conservative group which still promoted the ordination of women, but who opposed gay marriage, eventually gave birth to Christians for Biblical Equality in 1987, first led by Catherine Clark Kroeger, author of the 1990s book I Suffer Not a Woman, which shys away from the terminology of “biblical feminism.”

Debates continue to rage within the evangelical movement about the implications of “evangelical egalitarianism” on the one side and “evangelical complementarianism” on the other. Such terminology today seems to define the basic differences in the respective camps of thought.

Does an egalitarian interpretation of the Bible with respect to the equality of men and women necessarily entail an embrace of certain LGBTQ+ concerns, such as the redefinition of marriage? This is a slippery slope kind of argument, a logical fallacy as many have observed. Over the past one hundred years or more, there have been numerous strands of evangelical traditions which have embraced egalitarian interpretations of the Bible with respect to men and women, while still holding onto a traditional view of marriage between one man and one woman. One can think of several major denominations with an egalitarian bent that still hold to traditional Christian sexual ethics regarding marriage, ranging from the Nazarenes, the Assemblies of God, the Salvation Army, to various Pentecostal groups.

On the other hand, since the 1960s, numerous Christian denominations and churches have also moved in a more egalitarian direction with respect to relations between men and women, and within a generation those same denominations and churches have embraced redefinitions of marriage and understandings of gender, which would have been completely unknown just a few generations ago in the wider culture, and completely foreign to the 2,000 year history of the Christian movement. One can think of the Episcopal Church U.S.A, the United Churches of Christ, and most recently, the United Method Church.

Does complementarianism necessarily lead to abusive relationships, whereby men confuse their God-given position to lead in marriage, and even in local churches, with desires for control, leading to abuse? Some readers of recent biographies about Elisabeth Elliot have suggested, at least with Elisabeth’s third marriage to Lars Gren, that while complementarianism may not be directly responsible for abuse, such theology ends up enabling such abuse.

It would appear that the brand of complementarianism advocated by Elisabeth Elliot could lead to some undesired consequences. Elisabeth Elliot would offer some rather bizarre advice about a woman submitting to a man. For example, in the 1990s, she counseled that a woman should never give directions on where to go when a man was driving, even if she was the only person in the car who knew how to get to where they were going. Neither should a wife maintain and steward the family finances, even if the husband was handling the family finances in a manner that put the family in financial difficulties (Austen, chapter 33).

Encouraging a husband to lead and for men in general to lead spiritually in local churches, where much of the work is done by women anyway, is one thing. But such extreme forms of advice that Elisabeth Elliot gives would at times treat men as having fragile egos that should only be handled with kids gloves. At worst, such advice encourages a form of passivity on the part of a woman that can leave her needlessly vulnerable and ripe for exploitation.

As many have understood it, the principle of male headship requires that the man be the protector of woman, according to the apostle Paul: “Husbands, love your wives, as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her” (Ephesians 5:25 ESV). Nevertheless, Christians continue to debate as to whether this interpretation of a theology of male headship is grounded in the teachings of Scripture, or not.

Reflections on Elisabeth Elliot’s Legacy

In this book reviewer’s estimation, Elisabeth Elliot would have done well to hold to C. S. Lewis’ balanced position, instead of leaning to the one side of promoting male headship without sufficient attention to the sinfulness of all humanity, both male and female. Lewis’ views still need some tweaking, however. Aristotle may have said that “some people were only fit to be slaves,” but Aristotle meant this in terms of some people being created by God to serve only as slaves, whereas the Bible says no such thing.

On the other hand, God did create all people to be equal, male and female did God create them. The creational difference between male and female is integral to the order which God instituted. While the notion of having authority over another can be problematic, Lewis was right to suggest that there is nothing inherently wrong with leadership, even within a marriage. Consensus-making should be the ideal, but every social arrangement, whether it be on the largest scale as a nation, to something smaller like a business, or even a local church, down to the community of but a husband and a wife, needs some form of leadership to function.

Take any two people together as a social unit, at the smallest level, and you are never going to get to complete agreement on everything. We still should try anyway. But we should be realistic in knowing that trying to aim for consensus in every matter is simply an unrealistic pipe dream. The egalitarian ideal is very much that, a “fiction” as Lewis put it. When consensus is unreachable, leadership is necessary in order to make any progress. Tough decisions need to be made, and those who make them bear the responsibility for making those decisions.

Two people can not drive a car at the same time. One must take the driving wheel, while the other must not. Otherwise, you will have a recipe for a vehicle accident. But this need not imply going to the other extreme, whereby the passenger who knows which way to go should keep their mouth shut, while the driver keeps going round and round in circles. Leadership can be shared, as in one person driving while the other helps with navigation. Teamwork together does not require a car to be without a driver. This would be pointless. So, neither does consensus-making teamwork eliminate the necessity for leadership. If the wife has better accounting skills, this does not mean that having the wife handle the finances in any way undermines the headship of the husband. Every situation and family is different.

Lewis’ observation that maintaining this “egalitarian fiction” is necessary because of the human, sinful propensity to abuse power, which requires some form of system of checks and balances at play which can mitigate against abuse.

This is probably why it is better make a distinction between “patriarchy” and “complementarianism,” whereby the former pays little attention to the need for maintaining Lewis’ “egalitarian fiction,” and the latter which suggests that there must be a balance between clear leadership in a family and a means of recognizing the equal value and contributions of all parties involved on the other. In looking back over Elisabeth’s Elliot’s life and teaching, she rightly defended God’s creational design for order and leadership within the family, with the husband as prominent with respect to the wife. But it is also apparent to this reader that she also veered too much away from a balanced complementarianism towards an unhealthy authoritarian patriarchy.

Some on one side will disagree with me and insist that Elisabeth Elliot’s advocacy for male headship in marriage and in the local church enables abuse, leaving Christian women in a position where they will be continually vulnerable to abuse by men who use male headship as a means of maintaining unhealthy control of women. To follow Elisabeth’s views would unintentionally silence the voices of women, leaving them out of decision-making processes. Even when it comes to the exegesis of Scripture, over the past few decades there have been advances in scholarship which have called for serious re-examination of how to interpret several of the key biblical texts that Elisabeth appealed to. Perhaps Elisabeth Elliot misinterpreted 1 Corinthians 11:9, sandwiched inside of the complex Pauline passage about head coverings, the key “go-to” prooftext she used to defend her view (See the Veracity 2023 blog series on head coverings).

Recall that in Elisabeth’s three-fold approach to discerning God’s will, one of those steps included the “witness of the Word.” But if Elisabeth had misinterpreted certain passages of the Bible, even if such misinterpretations were only slightly askew, this might explain several of the life decisions she ended up making.

Such critics would say that Elisabeth Elliot was simply baptizing the American culture of her mid 20th-century youth, with its views upholding the primacy of men in comparison to women. We live in a much different world now in the 21st century, and we better get used to it. We need to adopt the newer readings of Scripture that revisionists say more closely approximate the original message which Paul was trying to communicate.

Yet on the other side, others will disagree with me and insist that Elisabeth Elliot’s advocacy for male headship was and is necessary, especially for those strong-willed women who assert themselves over and against God’s revealed plan. After all, Elisabeth Elliot herself admitted that she was a strong-will woman, who could be difficult to get along with. In one particular aspect of this critique, which Elisabeth might have endorsed, an argument is made that God speaks through the man and not through the woman. When a wife asserts herself, she is tempted to usurp the role given to her husband, and spiritual calamity will the ensue.

Furthermore, Elisabeth Elliot was only upholding what Christians have historically believed for hundreds of years, before the modern egalitarian era came along and disrupted the institution of the family. The forms of feminism emerging in the culture and seeping into the church were flooding a once Christianized culture with no-fault divorce, the normalization of premarital sex, the delay of and fear of marriage, and all other sorts of other cultural ills at odds with biblical truth.

Others will yet protest even more, believing Elisabeth Elliot to be a bundle of contradictions. She urged young women to take upon themselves the last name of the man they end up marrying, while Elisabeth Elliot still kept the last name of her first husband, even through her second and third marriages. Was Elisabeth being hypocritical by not going as “Elisabeth Leitch” or later as “Elisabeth Gren?” Or did she merely hang onto “Elliot” because that is who the Christian public knew her as an author, as a means of upholding her career?

The debate over Elisabeth Elliot’s legacy in the complementarian/egalitarian debate will surely continue for years to come.4

Gateway to Joy: Elisabeth Elliot’s Voice Via Radio

As she herself would admit, Elisabeth Elliot’s influence in the evangelical world went beyond her books and church speaking engagements. The success of her teaching later in her life over the radio made her a household name to yet a new generation of Christians, who never read the LIFE magazine story in the 1950s about the dramatic deaths of her first husband and four other American male missionaries in the forests of Ecuador.

The peak of Elisabeth Elliot’s influence was probably through her radio ministry by way of the “Gateway to Joy” program, which ran from 1988 to 2001. The program had its start with a 15-minute program for Back to the Bible, out of Lincoln, Nebraska. At first, Elisabeth was hesitant about speaking over the radio. As her announcer, Janet Wismer, tells the story, Elisabeth Elliot recorded the first 16 programs in one day. Hundreds of episodes later, having extensive experience as a public speaker, Elisabeth’s efforts at radio proved that she was quite a natural with the medium.

She would give all sorts of advice directed towards women, but that was often heard by men, too. She spent much of her time in her later years dealing with correspondence of listeners who often asked her for private advice, a task that she took seriously, though she was often overwhelmed by the number of requests for her advice. Careful to guard confidentiality, Elisabeth would often respond to such letters over the air, when it was deemed appropriate, and beneficial towards the whole of her audience, who often raised the same concerns and questions.

Gateway to Joy is still being rebroadcast on the Bible Broadcasting Network. My wife is a loyal fan.

It was towards those last few years of “Gateway to Joy” when Elisabeth Elliot started to notice some memory problems. She was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, a condition for which she suffered severely for the last decade of her life, robbing her of her ability to write and speak to audiences. Lucy Austen portrays her husband, Lars Gren, as being very steadfast and faithful in taking care of her in these debilitating years of Elisabeth’s cognitive decline. Elisabeth Elliot died on June 15, 2015, at age 88.

It is apparent that much of Elisabeth’s journals and papers kept during her marriage with Lars Gren were later destroyed by him. Perhaps we will learn more about what happened to this material in coming years, but there is still a lot we do not know about Elisabeth Elliot’s life.

As book reviewer Trevin Wax noted, all of the primary main characters in Lucy Austen’s Elisabeth Elliot: A Life, such as Jim Elliot, Rachel Saint, Addison Leitch, Lars Gren, and Elisabeth Elliot herself, were all complicated people, marked by both sin and sanctification. In other words, they were human. Lucy Austen does an outstanding job teasing out all of these complexities. I listened to an Audible audiobook version of Austen’s book, so I can only assume that Austen footnoted her research in the print and Kindle versions of her book.

Reflections on Elisabeth Elliot’s Biographies: By Lucy Austen and Ellen Vaughn

When I first started to read Lucy Austen’s Elisabeth Elliot: A Life, I had the impression she would be covering more of this last period of Elisabeth’s life than what I would later find in reading the two volume set of work by Ellen Vaughn, Becoming Elisabeth Elliot and Being Elisabeth Elliot. So I was a bit caught off-guard by some of the things that Vaughn, the authorized biographer of Elisabeth Elliot, said about Elisabeth’s marriage to Lars Gren, within the last few chapters of Vaughn’s second book. Vaughn had more things to say about Lars Gren than I had expected, considering that Lars is still living, but who is largely confined to a nursing facility at this late stage in his life.

Like Austen, Vaughn comments that Elisabeth’s decision to marry Lars Gren was perhaps the worst decision she made in her life. One wonders how much her opposition to the evangelical egalitarianism of her day contributed to her decision to marry Lars Gren. But was there something else really going on here?

Vaughn suggests that after about twenty years into the marriage the fence Lars put around Elisabeth was possibly doing more to crush her spirit than was the dementia that was settling in as Elisabeth aged. Family members and close friends even tried an intervention, and took Elisabeth away, with her permission, to an undisclosed location outside of the United States. They pleaded with Lars to change his ways. However, the intervention and separation period did not last long. Elisabeth eventually pleaded to go back to Lars. After all, Lars was her husband. In Elisabeth’s mind, Lars was her head, and she must go back to him.

Then surprisingly, after announcing to the reader that Lars eventually regretted destroying much of Elisabeth’s journals, written during the time of their marriage, Vaughn makes the oddest observation in the last chapter of Being Elisabeth Elliot: Lars Gren gave his life to Jesus in 2019.

This is both stunning and confusing. Lars had gone to seminary to become a hospital chaplain nearly some forty years before Elisabeth died in 2015. He had married Elisabeth, who surely would not have married such a man had she known that the man was not yet a believer in Jesus. So how is it that Lars and Elisabeth could have been married together for nearly forty years, supporting her in her Christian work, only to finally come to know Christ four years after her death?

It makes little sense to me. Was Lars pretending to be a Christian this whole time? Had Elisabeth succumbed to a kind of wishful thinking, thinking that Lars was already a believer in Jesus, when in reality, all of his demonstrations of piety were somehow all for show? Was Elisabeth’s desire for having a male head in marriage providing cover for Lars’ abusive behavior? Was he simply using complementarian theology as an excuse for explaining away his own control issues?

If Vaughn’s assertion that Lars Gren only experienced a late in life conversion is indeed accurate, then this fact should be factored in by critics who wish to lay the blame for the so-called ills of “purity culture” at the feet of Elisabeth Elliot. For if Lars Gren was not yet truly a Christian believer, then it could hardly be said that Lars was failing to fully obey Paul’s teaching, “Husbands, love your wives, as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her” (Ephesians 5:25 ESV), if indeed Lars had not fully understood what the love of Christ for his church was really all about until several years after Elisabeth’s death.

This statement about Lars’ 2019 conversion to Christ raises more questions than answers for me. It is unfortunate that Vaughn makes this observation towards the end of her work, without much further explanation, and it is odd that Lucy Austen never mentions this in Elisabeth Elliot: A Life. It is as though the last half of Elisabeth Elliot’s life still remains shrouded in mystery. Perhaps one day, we might know more about what really happened in this last period of Elisabeth Elliot’s life.

After finishing Lucy Austen’s biography, Elisabeth Elliot: A Life, which served as the framework for writing this book review series, I did finish listening to as well the two-volume biography by Ellen Vaughn, Becoming Elisabeth and Being Elisabeth Elliot. The work by both of these authors, Lucy Austen and Ellen Vaughn, are excellent, in my opinion, and both have distinct advantages. Austen’s work covers the whole of Elisabeth Elliot’s life in one volume, whereas Ellen Vaughn’s work is more detailed over the two volumes, focusing primarily on the early and middle stages of Elisabeth Elliot’s life. Both biographies pull out various details of Elisabeth Elliot’s life which the other biographer chose not to include, but having read both authors now, I have appreciated the perspective that both have given to her subject. I highly recommend the work of both authors.5

Elisabeth Elliot: A Remarkable Christian Woman

Whether you pick up a copy of Lucy Austen’s book Elisabeth Elliot: A Life, or the first book by Ellen Vaughn about Elisabeth Elliot, Becoming Elisabeth Elliot, the most gripping part of the story remains the telling about the five missionaries martyred on the river beach in Ecuador, in 1956. Even though I knew what was coming when reading both books, I was still taken aback by the courage and conviction of the men who died, along with the resiliency and abiding faith the surviving spouses had in the face of such suffering. As the Apostle Paul says in Philippians 1:21, “to live is Christ and to die is gain.”

Biographer Ellen Vaughn recalls that during various speaking engagements, Elisabeth would be often asked if she viewed the missionary work she engaged in among the Waorani people in Ecuador, in view of the tragic loss of her husband, to have been a “success.” Elisabeth believed that such a question simply missed the point of what the call to Christian obedience was all about. Success should be measured in terms of our act to obey the will of God, and not in terms of metrics as to the number of souls saved, how big a church gets, or some other factor considering variations of human behavior. Trials and suffering are an inevitable part of the Christian life, but what matters is trusting that God knows what he is doing as we seek to follow our Lord Jesus.

A quote of Elisabeth Elliot can sum up the message of her life for readers:

“God is God. Because he is God, He is worthy of my trust and obedience. I will find rest nowhere but in His holy will that is unspeakably beyond my largest notions of what he is up to.”

Well, I should wrap up this book review now. It is just about that time when my wife listens to another episode rerun of Elisabeth Elliot’s radio program, “Gateway to Joy.” I can hear the flute music along with the introduction from Elisabeth Elliot herself, quoting Jeremiah 31:3 and Deuteronomy 33:27: “‘You are loved with an everlasting love,’ that’s what the Bible says, ‘and underneath are the everlasting arms.’ This is your friend, Elisabeth Elliot.”

Notes:

1. Ellen Vaughn, in her second volume, Being Elisabeth Elliot recalls from Elisabeth’s journals one speaking engagement with college students prior to marrying Lars Gren, when a female student approached her after her talk, using vocabulary which flummoxed her: “Wow, that was kinda neat. I just really, really, want to thank you Mrs. Leitch. I mean, you know, it was just really great to just really learn some really neat stuff that I never just really thought of.” ↩

2. Ellen Vaughn notes that while Elisabeth appreciated all of the thoughtfulness Lars had for her, his dependability and efficiency, and how well he treated her as a total woman, knowing what her likes and dislikes were, she nevertheless found her conversations with Lars to be quite dull and boring.↩

3. Ellen Vaughn, in her Being Elisabeth Elliot, notes that is was not very long into her marriage with Lars that she began to realize the his desire to build a fence around her to protect her turned out to be something which she did not expect. The fence that Lars was building kept others out of Elisabeth’s life, even other family members. If Lars got upset with Elisabeth about something she said or did, Lars would often refuse to speak with her for several days, before eventually warming up to her again. After nine days being married, she confided with her closest friends and family members that getting married to Lars Gren was the biggest mistake she had ever made in her life. ↩

4. As my friend and interlocutor Andrew Bartlett says, nowhere in the Bible does it teach that men are to exercise authority over women, whether that be with respect to husbands and wives, or church leadership with respect to elders and non-elders in the local church. Elisabeth Elliot apparently held to a view of kephale , the Greek word in the New Testament often translated as “head,” has a strongly authoritarian association, as in a kind of top-down hierarchy, when it comes to “male headship” in the family and in the local church. Evangelical egalitarians argue that kephale is meant to be understood in the sense of “source” as opposed to “authority.” A more moderate view, as advocated by Anthony Thiselton, defines kephale in more of the sense of “prominence” or “preeminence.” Such a view of kephale understands “head” to more about being at the “head of the line,” as opposed to being the “head of a military unit” (like Elisabeth Elliot’s view) or “head of a river,” like most evangelical egalitarians today argue. Following Thiselton, a strong Scriptural and historical case can be made for wives submitting to husbands, and for qualified men and not women serving as elders in a local church., as “fathers” in a local church. Please see Veracity series on “women in ministry” for in-depth analysis. ↩

5. If you are more interested in honing in on the love story between Jim and Elisabeth Elliot, their daughter (Valerie Elliot Shepard) has published the correspondence between the two in Devotedly: The Personal Letters and Love Story of Jim and Elisabeth Elliot. This is great collection of original source material for understanding both Jim and Elisabeth Elliot.↩

December 22nd, 2024 at 11:06 am

Thank you for this well-done series. I learned a lot about Elizabeth Elliot as well as the history of a few topics (such as the feminism movement and how it was developed within the evangelical church etcetera).

LikeLike

December 22nd, 2024 at 4:38 pm

Thank you for commenting, and offering your positive feedback. Reading these Elisabeth Elliot biographies was very rewarding and provocative in many ways.

LikeLike

March 20th, 2025 at 7:52 pm

Wow, thank you so much for all the effort you put into this. I found it so helpful after finishing Vaughns work and feeling completely confused on the later half of Elizabeth’s life.

LikeLike

March 21st, 2025 at 9:22 am

Hi, Danielle. Reading the work of both Ellen Vaughn and Lucy Austen was worth the effort to try to figure out the latter portion of Elizabeth’s life. Thank you for the encouragement!!

LikeLike

May 7th, 2025 at 8:50 am

Thank for this review. It is so well done, covering many details. I listen to gate way to joy podcast.

LikeLike

May 22nd, 2025 at 7:14 pm

Thank you so much for this piece! I just finished Vaughn’s biography of EE and thought it was very well done. I’m so unsettled about her 3rd marriage and later years now, though. It leaves many question marks around her relationship with LG and how he treated her. His destruction of her journals during their marriage is so disturbing. I am glad she is in the company of her King now. She ran an extraordinary race, for which I am indebted.

LikeLike

May 22nd, 2025 at 8:59 pm

Thank you, Brittany. I share a lot of the same emotions and questions you have. Thank you for commenting on Veracity.

LikeLike

October 24th, 2025 at 10:25 pm

Just wanted to note that “Elisabeth Elliot” was Elisabeth’s (or Mrs. Gren’s) pen name, stated/clarified in one of her speaking engagements that I’m sorry I can’t name – just as children’s writer Jane Yolen is legally Jane Stemple (married in 1962 – sold her first book in 1961 – and her pen name stayed and is still Jane Yolen).

I don’t understand the ins and outs of Lars Gren, but I have to say that he was gracious when I ordered books directly from them. When Elisabeth died, I sent him a card and spoke of how impactful both her funeral and memorial were – that I had watched each a few times. He replied with a letter as well as a funeral program and offer of a DVD. He may have had his issues – indeed, Jesus DIED for him – but he also behaved generously on multiple occasions to one from whom he had nothing to gain (me).

LikeLike