Have you ever been troubled by what might appear to be contradictions between the four Gospel accounts? If so, then Dr. Michael Licona’s Jesus, Contradicted will help you to tame the doubts in your mind, and have a fresh look at the trustworthiness and reliability of the Bible.

I know because I have been there. Having not grown up in an evangelical church, I never heard of the concept of “biblical inerrancy” until my years in college in the 1980s. Growing up in a liberal mainline church instead, the Bible only had a secondary role in spiritual formation. As a teenager though, I read through all of the New Testament (except for Revelation), and I was wrestling through the things I read in the Bible. One of the first things I noticed is that there are differences between the four Gospels and how they report various speeches and events.

The idea that there were differences in the Gospels really did not bother me. If anything, the differences in the Gospels only intrigued me to look more closely at the New Testament. As Christian apologist and former cold-case detective J. Warner Wallace has said, the very fact that the Gospels DO have differences lends credibility to the authenticity of their accounts. For if all four Gospels said exactly the same thing, this would be evidence of collusion, which would raise suspicions about the integrity of the New Testament. Instead, because there were opportunities to smooth out the differences and the Gospel writers did not do so, this gives us greater confidence in the truthfulness of the Christian story.

But apparently, not every Christian is convinced that having differences in the Gospel is a good thing. Some argue that we should do whatever we can to harmonize the Gospels, even if some of those harmonizations come across as unconvincing, embarrassingly ad-hoc, otherwise severely strained.

Mike Licona, a New Testament scholar, is one of most able defenders of the bodily resurrection of Jesus, having debated Bart Ehrman, the world’s most well-known skeptic, on several occasions. Now, Michael Licona is arguing for a more robust view of biblical inerrancy, in Jesus, Contradicted:

My Faith Crisis Over Inerrancy

Michael Licona, author of Jesus, Contradicted: Why the Gospels Tell the Same Story Differently, has struck a chord with me. But I need to set up the story a bit more before I offer a review of this new book.

In the mid-1970’s, Harold Lindsell, who had been a professor at Fuller Theological Seminary, had popularized an idea to try to resolve the apparent contradictions in the various accounts of Peter’s denials of Jesus, on the night Jesus was handed over to the authorities to face trial and eventually to be crucified. Mark 14:72 and Luke 22:61 has Jesus saying that a cock would crow twice after Peter denies Jesus three times. But in Matthew 26:74-75 and John 18:27, a cock crows once after Peter denied Jesus three times. Matthew has Jesus predicting one cock crow, while John says nothing about Jesus predicting anything about a cock crowing.

Lindsell’s solution was to say that Peter denied Jesus a total of six times: three times before the first cock crowed, and then three more times before the second cock crowed. Other strict inerrantists arrive at similar conclusions, arguing that Jesus’ differing prophecies in all four Gospels must align together in all incidental details.

While this type of harmonization sort of “works,” it still really confused me. After all, all four Gospels explicitly state that Peter denied Jesus three times, not six times as Lindsell’s “inerrantist” interpretation suggested. I reasoned that if this type of convoluted logic is required to make sense of “biblical inerrancy,” then I simply could not accept it. I really wanted the Bible to be “inerrant,” but as a mathematics major in college I just could not force my mind to accept the idea that 3 equals 6.

I pretty much shoved the idea off of my mind, visiting it every once in a while, but I just could not get past the problem. It was not until I read Five Views of Biblical Inerrancy ( introduced and reviewed here on Veracity,) a multi-views book highlighting the perspectives of five different biblical scholars holding separate and distinct definitions of what constituted “biblical inerrancy,” that I finally had some peace about the matter. Not every proponent of “biblical inerrancy” holds to the rather strict version championed by Harold Lindsell.

This was quite a relief. I could now hold to a version of “biblical inerrancy.” My problem was that I still was not sure what that version of “biblical inerrancy” really looked like.

A few years ago, I got a copy of Michael Licona’s book Why Are There Differences in the Gospels?, oriented towards scholars, to try to help me. So far, I have only gotten part of the way through it until Dr. Licona came out with a shorter, more accessible revision of the book this year, Jesus Contradicted: Why the Gospels Tell the Same Story Differently. I am so glad I read this new book!

Jesus, Contradicted: Why The Gospels Tell The Same Story Differently, by Michael Licona, offers a more evidenced-based approach to handling differences in the Gospels, without resorting to tortured harmonization efforts concerning incidental details.

The Burden of Jesus, Contradicted: Towards a More Robust View of Biblical Inerrancy

Dr. Michael Licona is one of the most respected defenders of the bodily resurrection of Jesus Christ, having debated opponents like the UNC Chapel Hill skeptic, Bart Ehrman. In fact, the publisher of Jesus, Contradicted: Why the Gospels Tell the Same Story Differently gave the title for Licona’s book, as a kind of jab towards Bart Ehrman, whose New York Times blockbuster best seller Jesus, Interrupted, flew off the bookshelves when it first came out some 14 years ago.

But Michael Licona has had a problem with how evangelical Christians have typically viewed the doctrine of biblical inerrancy. Licona’s problem can be stated by way of my own example:

In 2 Timothy 4:13, Paul writes to Timothy:

“When you come, bring the cloak that I left with Carpus at Troas, also the books, and above all the parchments” (ESV).

Try this thought experiment out: Suppose we were to unearth a response letter from Timothy sent back to Paul, and it said something like this:

“Hello, brother Paul. Greetings from Ephesus. This is brother Timothy. About that cloak you left behind. I checked with Carpus and he said he did not have it. However, on my trip to Crete to see Titus, I noticed that he had your cloak. Apparently, you left your cloak with Titus in Crete, and not with Carpus at Troas. I will bring it to you when I get to Rome.”

Okay. We do not actually possess such a letter, but suppose we did. Suppose we were able to figure out some DNA-type testing to verify that Timothy actually wrote this letter. Yep. Paul forgot with whom and where he left his cloak. He made a mistake.

Would such revelation cause you to doubt your faith? Would then you be wondering whether or not Jesus really was divine? Would you begin to question the doctrine of the Trinity? Would you start to have doubts about the Virgin Birth? Would you begin to think that perhaps Paul was also wrong about the definition of marriage, as being only between one man and one woman? All because Paul could not accurately remember where and with whom he left his cloak?

My guess would be that the vast majority of Christians would not be too bothered with Paul misremembering where he left his cloak, or with whom he left it with. Nerdy people like me would be left puzzled by the existence of such a letter from Timothy to Paul, whereas most Christians would probably just go about continuing on with their day. If on the off-chance someone would have a type of crisis of faith over this, it might be time to ask some hard questions as to what or who they are putting their faith in.

As Michael Licona has said before about the resurrection of Jesus, if Jesus is risen from the dead, then Christianity is true: game, set, match. You do not need an inerrant Bible to believe that Christianity is true. Inerrancy is still important, however. Having a Bible that you can trust is very much essential, so inerrancy addresses this. But it is not necessary to establish inerrancy in order to know that Jesus is the Risen Lord.

This is just a thought experiment. We have no such letter from Timothy to Paul. If we did, it would not bother me if I discovered an incidental detail like this in our Bibles. However, for at least some Christians, little details like this make them feel very uncomfortable.

Without the Addition or Omission of a Single Detail?

Here is a good example of incidental details conflicting in the Gospels, highlighted by Michael Licona, from chapter 6 of Jesus, Contradicted . When Jesus is arrested and brought before the Jewish council, both Matthew (Matthew 26:64) and Mark (Mark 14:62), have Jesus saying:

“From now on you will see the Son of Man seated at the right hand of Power and coming on the clouds of heaven” (ESV)

But when Luke (Luke 22:69) is recalling the same speech Jesus gave in his Gospel, he differs from both Matthew and Mark:

“From now on the Son of Man shall be seated at the right hand of the power of God” (ESV)

Here Luke omits the reference to Jesus “coming on the clouds of heaven,” and he rephrases “the power” to read “the power of God.” (The omission of “you will see” near the beginning of the phrase in Luke should be trivial).

So, what is going on here? It is clearly a difference. But is it an “error?” Is this a “contradiction?” Hopefully, the answer should be a clear “NO,” but why?

One defender of a strict view of biblical inerrancy has been Johnston M. Cheney, is his 1969 printing of The Life of Christ in Stereo. Cheney’s work strongly influenced Harold Lindsell.

In the preface to The Life of Christ in Stereo, Cheney remarks that “the four Gospels agree together in all of their details and reveal the guiding hand of an unseen Author.” While Cheney is on the right track about the “guiding hand of an unseen Author,” it is puzzling as to what he means by “all of their details.” Further down in the preface, Cheney elaborates that the Gospels “agree so completely and minutely that they fit together into a single, coherent story, without the addition or omission of a single detail.”

Note that last phrase: “Without the addition or omission of a single detail.” This is a pretty bold claim by Cheney. So how does Cheney resolve the apparent discrepancy “so completely and minutely that they fit together into a single, coherent story,” between Matthew/Mark and Luke? Here is Cheney’s attempt to combine the various Gospel accounts together (Note that John’s Gospel completely omits this portion of the conversation):

“Hereafter will you see the Son of man sitting at the right hand of power and coming upon the clouds of heaven.”

Interestingly, Cheney omits the words “of God” after “the right hand of power” found in Luke, but which are missing from Matthew and Mark. But he adds “and coming upon the clouds of heaven” to Luke’s version. Is this what Cheney means by “without the addition or omission of a single detail?”

If this does not puzzle you, then you might as well skip reading the rest of this book review, and ignore Licona’s book. Save yourself some time, and go about the rest of your day. But if you are like me, and the cognitive dissonance is either unbearable, confusing, or at least mildly uncomfortable, please read on. Brace yourself and buckle up. THIS IS GOING TO BE A DEEP DIVE INTO SCRIPTURE.

Torturing Scripture to Make It Say What You Want It To Say?

Are you still with me?

Good. So let us dive in.

Johnston M. Cheney makes it look easy to harmonize Gospel differences. But in my mind, it just raises more difficulties.

Some might try to get around these difficulties by proposing that Matthew/Mark and Luke are recording two different segments of Jesus’ speaking at the Jewish council. Perhaps Matthew/Mark is telling us the first time Jesus spoke about the matter in front of the Jewish council. But then perhaps some were hard of hearing and so Jesus restates what he says with Luke’s version. However, this would be a really clumsy way of dealing with this. For what reason would Matthew/Mark record one part of the conversation, and completely omit the other, while Luke omits Matthew/Mark’s part, while adding to his account what Matthew/Mark omits?

Perhaps someone might even postulate that Jesus had two appearances before the Jewish council. Perhaps there was a group of Jewish leaders who arrived early at the council meeting who heard Matthew/Mark’s recollection of the story. Then another group of Jewish leaders arrived later, who did not hear Matthew/Mark’s version. So the session started all over again, featuring another repeat of the interview by the Jewish council, whereby Luke recorded what Jesus said in response in Luke’s Gospel. Neither Matthew nor Mark acknowledge anything about Luke’s version of the story, and neither does Luke acknowledge anything about the Matthew/Mark version of what was said.

Are any of these proposed reconstructions possible? Theoretically, yes. However, with all due respect, overly complicated proposals like these border on the side of sounding contrived, if not just plainly nonsensical. There must be a better, more convincing way of understanding these Gospel differences.

A Better Way of Understanding Gospel Differences

Michael Licona, in response, offers a different explanation as to why all of the details of Jesus’ appearance before the Jewish council do not line up perfectly. The reference to the “Son of Man” and “clouds of heaven” points the reader back to Daniel 7:13. It is important to know that Matthew and (presumably) Mark were Jewish, but that Luke was a Gentile, and that Theophilus, Luke’s patron mentioned in Luke 1:3, was probably a Gentile as well. Theophilus was probably not aware of the “Son of Man” teaching in Daniel 7:13, specifically the language about the “clouds of heaven.”

Unless Theophilus was a student of Jewish literature, which he probably was not, the “clouds of heaven” would not have meant much to him regarding any claim to divinity. But to a Jewish audience, the “clouds of heaven” language was associated with a claim to divinity, which explains why the high priest immediately tore his robes upon hearing Jesus speak, in Matthew’s version, thinking this was blasphemy.

As most scholars like Licona say today, Matthew probably knew Mark’s version of the story, and kept it pretty much as is in his version. On the other hand, Luke probably also knew Mark’s version of the story. But he was not satisfied with the way Mark presents his version, so Luke freshens it up a bit.

In order to make Jesus’ saying more comprehensible to Theophilus, Luke most probably removed Matthew/Mark’s “coming on the clouds of heaven,” changing what Jesus said by simply adding the phrase “of God,” in order to clarify to Theophilus that Jesus is making a divine claim about himself. Theophilus could then better understand why the council elders freaked out when they heard Jesus’ words (Luke 22:70-71). The matter makes even more sense when one realizes that Jesus was probably speaking Aramaic at the Jewish council meeting, and our Gospels were written in Greek, which required all three Gospel authors to provide a translation into Greek of what Jesus said in Aramaic.

Consider an idiomatic expression we use today in contemporary English. When I was growing up in Virginia, I would commonly hear expressions like, “Have a good day” or “Have a good evening,” as a way of saying good-bye. However, within the past decade or so, I commonly hear the phrase “Have a good one.”

In my parents’ generation, to say something like “Have a good one” would have been unfamiliar. “Have a good one… what?” What does the ‘one’ mean? Grammar experts tell us that the phrase only originated sometime in the 1970s, but in my part of Virginia it has practically replaced “Have a good day” or “Have a nice day” over the past decade or so.

So, by changing what Jesus said in Mark/Matthew’s version was Luke lying to his readers? Was he being deceptive? Is God trying to trick us by leaving this in our Bible?

Hopefully, your conclusion should be “Of course not!”

The point here is that Matthew/Mark and Luke are telling different versions of the story in order to achieve the purposes for which they are writing. By changing Jesus’ actual words the Gospels are not contradicting one another, nor is any real “error” being committed. Instead, Luke is changing the words of Jesus in order to give clarity to his Gentile reader, explaining something that would have been obvious to the readers of Matthew/Mark.

The idea of the Gospel writers “changing” something that Jesus said may make us uncomfortable. It may make us feel like “sliding down some slippery slope.” But if the change being introduced actually communicates the teaching of Jesus more effectively to the different audience of the particular Gospel writer, in alignment with the particular Gospel writer’s purposes, then there is no harm being done. In fact, the exact opposite of what is feared is the case, as the Gospel writer intends to give greater clarity to the teaching of Jesus, so that this different audience can better understand the timeless message of Jesus.

This is a good thing. Staying true to the message of Jesus is anything but “sliding down some slippery slope.” Staying true to the message keeps us from sliding down some feared “slippery slope.”

All three Gospels are giving us the “gist” of what Jesus said at his arrest and appearance before the Jewish council. This is what Michael Licona is aiming at by arguing for a “flexible inerrancy” instead of a rigid “strict inerrancy,” which has a tendency to get hung up incidental details.

This is also a problem when some defenders of a strict view of inerrancy try to fit together everything into a single, coherent story, ” without the addition or omission of a single detail,” like what Johnston M. Cheney did by actually adding and omitting details in his version of the Gospels….

….Or when a Bible scholar in discussing Peter’s denials of Jesus tries to tell me that 3 equals 6, without any further explanation.1

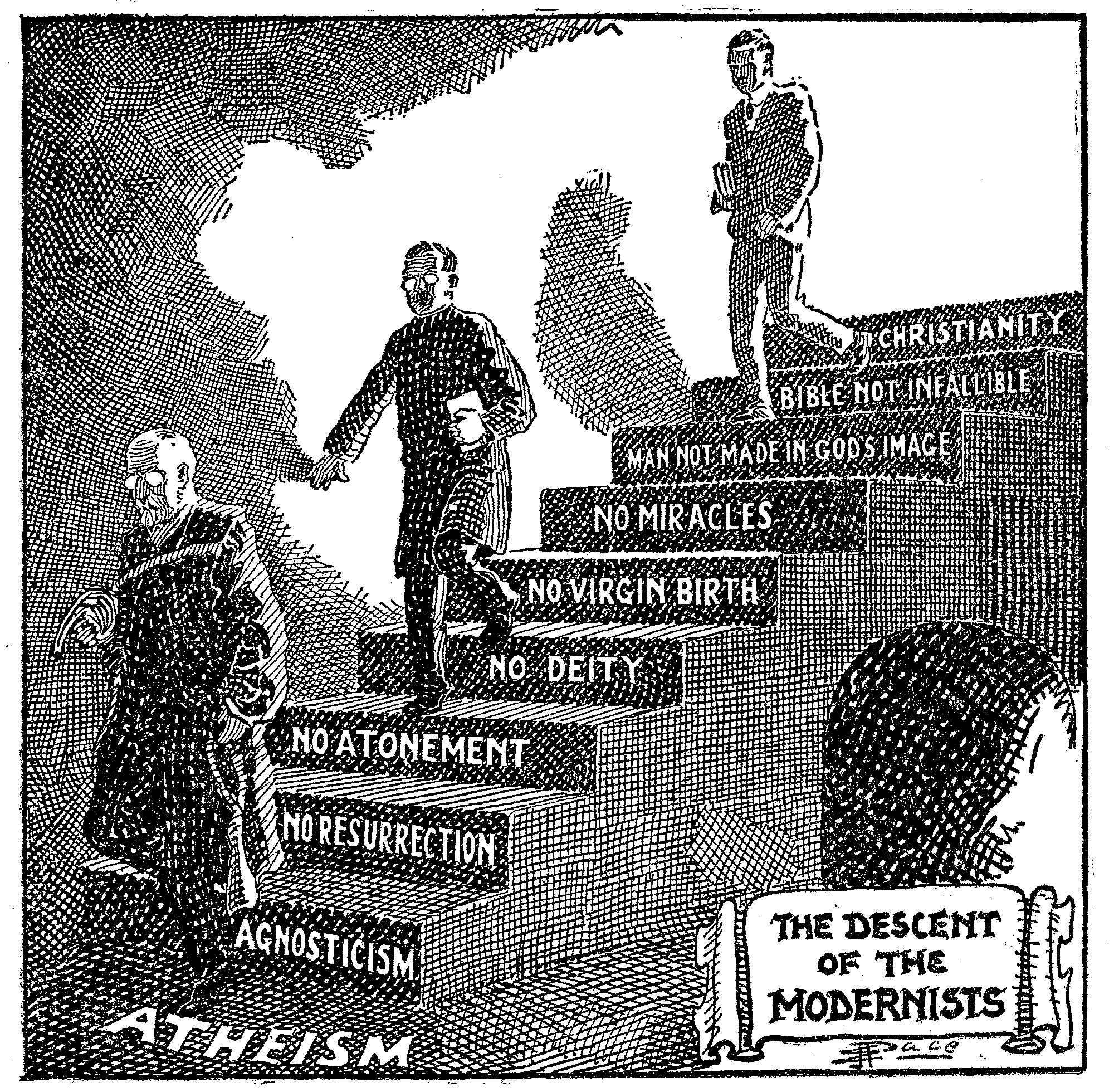

Descent of the Modernists, E. J. Pace, 1922. Many have slid down a slippery slope towards unbelief. But is such a slide inevitable? A more robust view of biblical inerrancy might help a new generation of believers to have more confidence in their faith in Jesus and the integrity of the Bible.

The Gist of the Story

The problem is that this example from the arrest of Jesus is just one of dozens and dozens and dozens of differences found between the four Gospels. In 1776, a most pivotal year in world history according to author Andrew Wilson in his excellent Remaking the World, the German scholar Johann Jakob Griesbach published the first ever synopsis of Matthew, Mark, and Luke together, side-by-side. Griesbach’s work demonstrated the large number of differences between the Gospels, which most Christians never bother to consider, mainly because most Christians never bother to sit down and read all four Gospels, and compare them with one another. Since 1776, thinkers who have drunk deeply from the wells of Enlightenment thought have questioned the trustworthiness and reliability of the Bible. In response to these challenges, Christians have not always done very well in providing convincing explanations for these differences we find in the Bible.

I wish it were true that Johnston M. Cheney could craft a “Life of Christ in Stereo,” taking into account every single minute detail, and eliminate all the differences we see in the Gospels. Alas, just from this one example alone from above, this is not the Bible we have. The Bible we have is the Bible we have, as Griesbach has shown us. This will make some uncomfortable and even anxious. But it need not be the case. At the same time, it does no good to pretend that such differences in the Gospel do not exist; that is, unless you prefer to be like an ostrich, and stick your head in the sand, hoping that the problem might go away on its own.

Consider the problem from this angle. Look at the use of hyperbole in the Gospels. You can see this without doing a side-by-side comparison of the Gospels.

For example, when John the Baptist begins his ministry, Mark 1:15 says that “the whole Judean countryside and all the people of Jerusalem went out to him. Confessing their sins, they were baptized by him in the Jordan River” (NIV). Are we to believe that every single last person in Judea and the city of Jerusalem, such as all of the Pharisees and other Jewish leaders who opposed John the Baptist, and including people like King Herod and the Roman pagan Pontius Pilate, all went down to get baptized in the Jordan River by John the Baptist? Of course, not. This is hyperbole. This is in our Gospels.

When we read at Christmas time about the decree by Caesar Augustus, that “all the world should be registered” for a census (Luke 2:1 ESV), does this mean everyone living on planet earth? Did Caesar Augustus secretly make trips to the Americas to discover the Mayans and Alaskan Eskimos to make sure they got registered in the census, only to completely erase the historical record about the existence of the Americas until Columbus “rediscovered” the New World in 1492? Of course not. This is hyperbole. This is in our Gospels.

This is all exaggerated language meant to have an artistic, literary effect. We use such exaggerated speech in our everyday language all of the time, and we never judge one another for lying and being deceptive when we say such things. Was “everyone” out at the ball game yesterday? Was “no one” at the grocery store last night, even though there were still ten cars in the grocery store parking lot, when there are normally a hundred cars in the parking lot during the day?

If even individual Gospel authors were willing to repeatedly use hyperbole in their writings, then it should not surprise us that we might find differences in our Gospels. Does the use of hyperbole in the Gospels present a problem for biblical inerrancy? Well, that all depends on how you define “inerrancy.” In Michael Licona’s definition, and in my definition as well, it does not.

In Jesus, Contradicted, Dr. Michael Licona has done the hard work to show where at least some of these differences exist in the Gospels, and how they might be reconciled with one another, or otherwise made sense of. Most of these differences involve incidental details. They can be reconciled with one another, not by always resorting to some forced, ad-hoc harmonization technique. Rather, once one understands the literary genre of the Gospels, the reader can better understand why the Gospels often differ with one another.

As Michael Licona puts it, the Gospels give us the “gist” of what Jesus is saying and what he did. The various incidental details, and their differences we encounter along the way when reading the Gospels, should not bother us. Once one gains an appreciation for how the ancient literary genre associated with the Gospels actually works, the Bible reader can have a better confidence in the Bible as the fully inspired, inerrant Word of God. However, not everyone will be convinced by Licona’s defense of this “flexible inerrancy” perspective.

The Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy: Having the Final Say?

The Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy was drafted by a team of evangelical scholars and spokespersons in the late 1970s. Since the 19th century, many evangelical Protestants believed that certain advances in the sciences had cast some doubt on the inspiration of Scripture, thus causing some to lose confidence in the Bible’s authority as the defining source for truth. Since our knowledge of Jesus Christ comes primarily from the Bible, it made sense to secure a more firm footing for the authority of the Bible. A definition of biblical inerrancy was adopted in response to the forces of skepticism that had arisen in the age of modernity. The challenge was in crafting a definition which could garner support from a broad collection of various conservative denominations, churches, and scholars, without trying to force the Bible into a mold which would not properly fit the Scriptures.

As a result, the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy has had some qualifications as to how to define inerrancy. For example, biblical inerrancy only applies to the original autographs.

The papyrus containing the original words penned by those like Paul, John, and Peter in our New Testament are lost. They have been lost for quite some time. What we do possess are copies of those originals. The problem is that we have thousands of copied manuscripts that do not match up perfectly with one another. The manuscript tradition handed down to us two thousand years later has numerous errors.

There are thousands of these errors, but it is well known that such errors do not impinge on any substantial area of Christian doctrine. The vast bulk of such errors are all minor, mainly spelling errors and the like, introduced by copyists over the years making inadvertent changes to the text. Nevertheless, these incidental errors are still all errors.

What this means is that the Chicago Statement acknowledges that the very Bibles we possess on our smartphones, tablets, and paperbound books still are not inerrant. Inerrancy only applies to the original autographs which we no longer have. Unless one is a “King James Onlyist,” who believes that the manuscript tradition used by the King James Bible translators of 1611 has been preserved down through the centuries without any errors, no Christian today can claim that our current Bibles are fully inerrant, according to the Chicago Statement. Since most Christians today regularly read from modern translations based on more updated manuscripts that the KJV translators did not have access to in 1611, like the ESV and NIV, it becomes more apparent that by the definition set by the Chicago Statement, your English Bible in your hands today is not without error.

The restriction of inerrancy to original autographs was not the only qualification the framers of the Chicago Statement sought to define. The Chicago Statement also draws the line to say that grammatical errors in the original text do not impinge on the doctrine of inerrancy.

Bible scholars have known for a long time that the Greek grammar used in the Book of Revelation is not very good, particularly possessing a number of “irregularities” regarding the use of certain Greek verb tenses. Some commentators have said that John thought in Hebrew or Aramaic, but that he wrote in Greek… but not very good Greek.

David Aune, who wrote one of the most well known commentaries on the Book of Revelation (Word Biblical Commentary, Vol. 1), comments: “The Greek of Revelation is not only difficult and awkward, but it also contains many lexical and syntactical features that no native speaker of Greek would have written.” Going way back into church history, some Greek copyists of the Book of Revelation would try to fix some of the Greek grammar errors, resulting in a wide variety of manuscript copies. Dionysius of Alexandria, an early 3rd century church leader, notes about the author of Revelation “that his use of the Greek language is inaccurate, and he employs barbarous idioms” (Eusebius Hist eccl. 7.25).

I am no Greek scholar, but we might be able to use an example from English grammar: If John were to use a dangling preposition in Revelation, an incidental detail but an grammatical error nonetheless, it should not cause us to doubt the inerrancy of Scripture, and question the Second Coming of Jesus. Likewise, if we were to unearth a letter from Timothy back to Paul saying that Paul actually left his cloak with Titus in Crete, this should not cause us to doubt the inerrancy of Scripture either. Perhaps there is another reason why God would permit such phenomena to appear within the sacred text.

The driving principle behind a robust understanding of inerrancy is to say that God is completely trustworthy and reliable in giving us the Bible as our authority as it is, even when we discover certain minor phenomena which might raise some questions. The main point that inerrancy is trying to address is the message that God wishes to communicate to the reader, not the incidental minutiae details encountered along the way.

The Bible Is Trustworthy and Reliable. God Is Not Deceiving Us in The Bible

But back to my hypothetical example, if Paul did misremember where he left his cloak, and with whom he left it, this in no way suggests to me that either God or Paul was trying to be deceitful. Though not entirely like my example, we actually have an example of Paul admitting a memory lapse, whereby Paul is unable to remember who all he baptized in 1 Corinthians 1:16. Again, this acknowledgement by Paul is not an attempt to deceive the reader, though it does raise the question as to how and why such a statement would be found in our inspired text.

To me, the most important aspect of biblical inerrancy is to say that the Bible is completely trustworthy and reliable, and that God is no way trying to deceive me or you as the reader. However, it does mean that there are differences in the Bible that at the very least, on the surface level, might indeed look like “errors.” These are instances where perhaps a traditional interpretation does not work as well as a more thoughtful, nuanced interpretation which takes the concept of literary genre into account. These are not “contradictions” which rise to the surface of challenging a flexible view of biblical inerrancy.

The grammatical errors in John should not cause people to doubt Scripture. This should be fairly obvious, mainly because few read the New Testament in Greek, and most do not care, preferring to trust our English Bibles. However, the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy does not fully address other issues encountered when readers study the Bible more closely, in English. Granted, the Chicago Statement acknowledges certain literary features, such as the use of hyperbole and round numbers, which are present in the Bible but that do not violate the principle of inerrancy.

Yet people who study Scripture diligently observe other phenomena such as Paul loosely quoting Old Testament texts here and there, omitting words at times, or even taking parts of two different Old Testament verses and combining them together. Genesis 1 gives us a description of oceans below and oceans above our heads, yet only in the most rare situation would you find a Christian insisting that the Bible “teaches” that the earth is flat. The Bible repeatedly uses the language of the “heart” to refer to the seat of the emotions, while modern science tells us that the heart is mainly a pump, which lacks any specific cognitive function associated with human emotion. The various resurrection accounts have differences between them. Matthew 28:1 says that two women went to the tomb on Easter morning. Mark 16:1 says three women went to the tomb. But every fully-professing Christian I know accepts that Jesus bodily rose from the dead, even though there are a number of differences between the resurrection accounts like this.

Greco-Roman Compositional Devices

If someone holds to a strict view of inerrancy, this might trigger the unintended consequence of causing them to doubt inerrancy, if they were to study Scripture more closely and finding supposed “errors” which they can not resolve under a strict inerrancy mindset. For example, the Chicago Statement talks about “free citations” of the Old Testament as not being in conflict with inerrancy. But the Chicago Statement itself does not go into great detail in defining that. Licona’s point is that we need to address those kind of incidental details in Scripture so that students of Scripture can have a greater confidence in the inerrancy of Scripture, not less.

The contribution that Michael Licona brings to the discussion is a careful examination of the literary genre of the Gospels themselves. Dr. Licona looked at biographical studies done by other first century Greco-Roman authors, contemporaneous to the Gospels, most importantly the work of Plutarch. Along with other historians of the day, Plutarch wrote “lives” about important public figures of the day.

However, unlike modern biographies, which tend to focus on precise chronological details concerning a person’s life, Greco-Roman authors like Plutarch were more concerned about giving a description of the character of the person being studied, as opposed to a more modernist approach which emphasizes precise chronology. Unlike modern historiographers, skilled Greco-Roman authors like Plutarch were expected to employ certain compositional devices, changing or rearranging the details, in order to more faithfully and accurately present the character of the person being studied.

The importance of this can not be underemphasized. It was not simply that a number of ancient historiographers used such compositional devices: They were expected to do so, as this was part of their educational training, as described in various ancient compositional textbooks.

For example, one such compositional device in antiquity was displacement: “When an author knowingly uproots an event from its original context and transplants it in another, the author has displaced the event” (Licona, Why Are There Differences in the Gospels, p. 20). The author decides to reframe the historical narrative to better fit the purpose of describing the character of the person.

While such displacement would be looked down upon by modern historiographers, the art of displacement was the norm according to the literary standards of the day, when the situation called for it. Furthermore, such examples of displacement can be found in the Gospels themselves, demonstrating that the Gospels were written according to these ancient literary standards and not modern ones. As a result, many New Testament scholars today have concluded that the Gospels do not fit within any modern concept of “doing history,” nor do the Gospels fit within their own, unique literary genre. Instead, the Gospels are great examples of Greco-Roman “bios,” the same literary style used by a contemporaneous author like Plutarch.

Luke Omits the Journey of Baby Jesus and His Parents Down to Egypt: A Compositional Device in Action

For example, it is well known that the Gospel of Matthew includes in Jesus’ infancy narrative a description of the Holy Family’s flight to Egypt, in order to escape the wrath of King Herod, who proceeded to wipe out the baby boys of Bethlehem, in order prevent any potential usurper from being a threat to Herod’s reign (Matthew 2:13-15). Only after Herod’s death did the young Jesus and his parents make their way to settle in Nazareth up in Galilee.

This story differs from Luke’s narrative, in that after the birth of Jesus, within a few days Jesus was taken to the Temple in Jerusalem to be presented for the purification ritual. Then after that, the family resettles in Nazareth. No mention is made of the journey to Egypt and back to Israel as found in Matthew (Luke 2:22-40).

Why does Matthew have the Egypt episode and Luke does not? Part of what Matthew does in his Gospel is to cast Jesus into the role of the new Moses, the one who journeys out of Egypt to Israel, to establish a new sense of the “Promised Land.” Just as through Moses God delivered the people out of physical slavery, so did through Jesus God delivers the people out of spiritual slavery. Matthew has a theological purpose meant to describe the character of Jesus, one that differs from the literary objective that Luke has in writing his Gospel. Since Luke is a gentile, and his patron, Theophilus, is probably a gentile as well, making an appeal to Jesus as the new Moses would not have meant that much to Luke’s audience, so he skips the story.

Licona argues that such artistic messaging is found over, and over, and over again in Plutarch’s Lives.

This also might very well explain why Matthew describes Jesus’ most famous sermon as the “Sermon of the Mount” (Matthew 5-7), whereas Luke has the same material presented as the “sermon on the plain” (Luke 6:17-49). While this is difficult to establish with a high degree of certainty, it might be reasonable to suggest that Mathew has displaced the event of this famous sermon away from the “plain” where Luke situates it to a “mountain” in Matthew’s Gospel.

Here again, Matthew wants to highlight Jesus in the role of the new Moses. Whereas in the Moses’ story, Moses returns down from Mount Sinai with the Ten Commandments, Jesus delivers his greatest sermon with a new set of commandments on a mountain as well. It is also reasonable to suggest that the famous teachings of Jesus from these sermons were preached on multiple occasions, whereby both Matthew and Luke are retelling some of Jesus’ “greatest hits,” but just placing them in different settings.

Modern methods of doing history would not support what Matthew has done here, but it is important to recognize that Matthew is a first century historiographer and not a 21st century historiographer. Essentially, the Gospels are a mix of historical narrative and more artistic elements added in along the way to give us a better appreciation of the character of Jesus, the main character in the Gospels.

Here is a short list of some compositional devices found in Greco-Roman historiographies, such as in what Plutarch wrote. Licona discusses each compositional device, along with examples, in his book:

- Compression

- Conflation

- Literary spotlighting

- Transferal

- Displacement

- Composite citations

- Editorial fatigue

Plenty of other examples of the Greco-Roman “bios” genre can be found in the Gospels. Luke’s adding the phrase “of God” to “the power,” mentioned above in this blog post (Luke 22:69), is an example of “elaboration,” another well-known compositional device used by Greco-Roman authors of the time. In chapter 7 of Jesus, Contradicted, Licona brings up Matthew 5:29-30, whereby Jesus instructs his disciples with this: “if your right hand causes you to sin, cut it off and throw it away” (ESV). The early church father Origen reportedly once took this teaching in the most non-metaphorical way possible and castrated himself, and he was ridiculed for his action by other early church fathers!

Licona cites a letter from the famous ancient philosopher of the first century, Seneca, to a friend. Seneca advises his friend: “Vice, Lucilius, is what I wish you to proceed against, without limit and without end. For it has neither limit nor end. If any vice rend your heart, cast it away from you; and if you cannot be rid of it in any other way, pluck out your heart also.” While Matthew 5:29-30 alone provides no limit to what Jesus is asking, which perfectly explains why Origen took such extreme measures, this well-known quote from Seneca frames how we should interpret Jesus’ words in Matthew. We are to avoid vice-prone behaviors, but clearly Seneca was not advising Lucilius to kill himself by mutilating his own heart. Jesus’ teaching is clearly hyperbolic, according to other literature from the Greco-Roman world.

Speaking of Origen, who lived in the late 2nd to early 3rd century, he was one of the earliest Christians to argue that whenever you find something that looks like a contradiction in the Bible, the Christian reader should re-focus their attention on finding the spiritual meaning that the text is trying to communicate to the reader. In comparison, Saint Augustine, who lived in the late 4th to early 5th centuries, was more inclined to use certain harmonization techniques in resolving Gospel differences, more so than Origen. But even Augustine recognized limits to certain harmonizations, more so than many readers of the Bible today are willing to recognize. Licona brings Origen and Augustine into this discussion in Jesus, Contradicted, to support his thesis.

Rome’s famous Colosseum, right before dusk (October 2018). In Jesus, Contradicted, Michael Licona argues that Greco-Roman authors, like the historian Plutarch, can help us to understand why there are differences in our Gospels, thereby encouraging believers to have greater confidence in the integrity of the New Testament.

Some Pushback Against the Application of the Greco-Roman Compositional Devices Thesis?

Some pushback is warranted as to how Michael Licona handles certain applications of Greco-Roman compositional devices on specific passages, and how they relate to inerrancy. Licona identifies a handful of examples that are difficult to resolve via traditional harmonization techniques.

For example, consider the geography around the Sea of Galilee. Capernaum is on the northwest shore of the Sea of Galilee. Bethsaida is somewhere around the north to northeast side of the Sea of Galilee. Here is a classic difficulty regarding differences in the Gospels. After the feeding of the 5,000, Jesus instructs the disciples to go across to the other side of the lake. Mark 6:45 says that Jesus told the disciples to go to Bethsaida. Yet John 6:17 says they set off for Capernaum. So, which is it?

Licona argues that a traditional harmonization, which has the disciples intending to go Bethsaida, but were blown off course to land in Capernaum, does not work. Licona suggests in his academic book, Why Are There Differences in the Gospels?, that “John slightly compresses or one or more of the evangelists artistically weave elements into their narrative that were not remembered in a precise manner,” consistent with some compositional device that Plutarch might have used (Licona, Why Are There Differences in the Gospels?, p. 138).

Craig Blomberg, another evangelical New Testament scholar, argues that a different harmonization proposal is better, and does not require an appeal to Greco-Roman compositional devices. It is quite possible, if not more probable, that Jesus knew that the weather was going to be bad, so Jesus told his disciples to head towards Bethsaida (following Mark) and then head towards Capernaum (following John), in order to stay close to the shore and more out of the rough weather.

I think Craig Blomberg is probably right, and Michael Licona is probably wrong in this particular example. If I look at this a bit more closely again, I might be persuaded by Licona, but in looking at the evidence thus far Blomberg for me has the simpler solution.

In other words, sometimes a different but more straight-forward harmonization approach has enough explanatory power to resolve a biblical discrepancy. We need not always jump towards a compositional device approach advocated by Michael Licona. It really depends on each particular Gospel difference being studied.

Licona also cites the timing of the census under Caesar Augustus, where Luke traditionally interpreted indicates that Jesus born during the time of that census in Bethlehem, as a potential error in Scripture, in Luke 1:80-2:7. Most scholars contend that this census happened in 6 A.D.. almost a full decade after the traditional birthdate of Jesus, probably between 4 B.C. and 1 B.C.. Licona does not know this conflict can be resolved.

However, Licona does not seem aware of David Armitage’s paper from the Tyndale House, in 2018, which suggests that the Greek of this passage could be translated as saying that Luke explains why Joseph had property interests in Bethlehem, associated with the census, but that the census itself could have happened up to a decade after Jesus’ birth. This might qualify as an example chronological displacement, much like what is found in some of Plutarch’s compositional devices.

Consider just one more example: In Matthew 8:14-23 and Luke 9:51-62, someone comes up to Jesus and asks about wanting to follow him wherever he goes. Both Gospel writers respond with Jesus saying, “Foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head.” However, Matthew situates this episode in Galilee, in the midst of his ministry there. Luke, on the other hand, situates this episode when Jesus makes his way towards Jerusalem, following after his ministry in Galilee, near where Jesus and his disciples are passing by Samaria.

In an interview with Sean McDowell (linked below), Licona suggests that one of the Gospel writers, probably Luke, displaced this event to happen after the Galilee ministry because Luke’s source misremembered where Jesus made this statement. So, Luke just placed this event there for some reason we do not about, under the assumption that Luke did not know exactly where and when the event actually happened (Licona, Jesus, Contradicted, p. 141ff).

However, a different type of harmonization, along with a compositional device, might be an easier solution. It is quite possible that Luke placed this event in his narrative while Jesus was heading towards Jerusalem for a theological reason, in order to signal to his readers that following Jesus would be costly, as Jesus heads towards the cross. The suffering of Jesus surely would have caused some of his Galilean followers to think about the plight of Israel as a people, under the thumb of Seleucid Greeks and finally the Romans, for several centuries leading up to the period of Jesus’ earthly ministry. Luke was more concerned that his readers picked up on the meaning of “Foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head,” as opposed to giving us a strict chronology of events.

Furthermore, since Luke was not an eyewitness to these events but rather obtained his story from other sources, the theological messaging might have originated with Luke’s source, and not Luke himself. Licona does not discuss this plausible theological reasoning on Luke’s part, a curious omission. Licona in places seems too quick to chock up placement of certain passages in the Gospels due to a failure to remember a specific chronology, when it might be more plausible to see that the Gospel writer had a theological motive in doing what they did.

This type of signal is not obvious to most modern readers of Scripture because the signal is not explicit. But to a first century audience, immersed in the world of Second Temple Judaism, those readers probably would have picked up the theological messaging with greater clarity than we typically do today. Unless we have a commentator in the early church, or an early church council, which specifies a different reading, it seems reasonable to suggest that the Gospel writers have certain theological motivations for presenting their material that accounts for such discrepancies between various Gospels. We may not be able to identify the exact theological motivation here from our 21st century vantage point, but it does not mean that such a theological motivation is not present.

Nevertheless, these criticisms do not in any way undermine the core of Licona’s thesis.2

Other Pushback Against Michael Licona’s Thesis?

The more earnest critics of Licona’s thesis will undoubtedly aim at undermining his argument that the Gospels are an example of Greco-Roman “bios” (or biography), or at least belonging to some other literary genre having common features of Greco-Roman “bios.” They might argue that placing the Gospels in an ancient literary category is making some appeal to something outside of the Bible in order to explain the Bible, as though that is somehow a bad thing. These critics are concerned that by doing this, a scholar is lowering the inspired nature of the Scriptural text. For such critics, Michael Licona’s “flexible inerrancy” is too flexible. They would conclude that Michael Licona has gone too far.

On the other side are those, even Christians, who will deny the inerrancy of the Bible because it does not fit with their attempts to press the boundaries of what constitutes “historic orthodox Christianity.” For them, Michael Licona’s proposal does not go far enough.

A good example of this stretching of the Scriptures is found when Brian McLaren, a former “Emerging Church” leader, insists that Jesus made a “mistake” when he told his mother (Mary) that his time had not yet come, when they ran out of wine at the wedding at Cana in John 2. Jesus went ahead and performed the miracle of turning water into wine anyway. McLaren infers from this that even God makes mistakes, and therefore, can change his mind. This is no minor, incidental issue, as McLaren’s inference changes the message of the Gospel of John, something that Michael Licona’s “flexible inerrancy” does not allow. For if God can change his mind, as McLaren suggests, it might suggest that God can change his mind about standards of sexual morality, for example.

Then there is the case of philosopher Lydia McGrew, an evangelical who rejects Licona’s proposal, but who ironically denies the inerrancy of the Bible. Go figure. McGrew has some of the more determined criticism of Michael Licona’s thesis, as in her criticisms about citing “editorial fatigue” at times in the Gospels, for example, and she may have some good points here.

However, such criticisms against Michael Licona’s thesis are ultimately counterproductive. Asserting that we have definitive examples of errors in the Bible is taking a rather defeatist position. Yet on the other hand, the more common assumption is that some want the Gospels to be a type of narrative of the exactitude quality of a police deposition. However, this is not what we have in the New Testament.

Nevertheless, the Christian faith is an evidenced faith. We believe Christianity to be true, not simply because the Bible says it is true. Rather, we believe that Christianity is true because the evidence taken on the whole, both within the Bible and outside of the Bible, points to the veracity of the truthfulness of the Christian message.

Seneca’s letter to Lucilius is just one example among many of material outside the Bible informing how we should interpret the Bible, when the Bible is unclear or silent about a particular question, and the early church record does not adequately address the question. We simply can not “make up” some interpretation of a passage, and then claim it as a result of some supposed “compositional device” from Greco-Roman literature, without sufficient evidence to back up the claim being made.

Furthermore, the fact that such differences do exist in our Gospels must be understood within the context of the sovereignty of God. In other words, God knew what he was doing by giving us the Bible we possess.

Licona’s focus is on the message of the Bible being inerrant, without being encumbered by incidental details and minutiae which are not relevant to the message being taught in the text. For each ancient compositional device Michael Licona references, he offers convincing examples from the Gospels to support his case. Readers should thoughtfully work through Michael Licona’s many examples in the book to see if I am correct about that.

Signing the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, in October 1978, by 200 evangelical leaders. Is it time to revise the statement, or are we better off keeping it as is, or look to something simpler, like the Lausanne Covenant?

The Chicago Statement Versus the Lausanne Covenant

The last few chapters of Jesus, Contradicted will be the most controversial for those who think Michael Licona has gone too far (or not far enough). In those chapters, Licona maintains that because the Chicago Statement assumes a rather insufficient and under-developed understanding of the inspiration, or “God-breathed-ness,” of Scripture, the effort to successfully define inerrancy ultimately falls short. Licona is not alone in his judgment.

Some sympathizers of the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, put together in 1978, say that though well intended and promoting a needed sense of unity among evangelicals during the 1970s, the statement tries too hard in attempting at a definition of inerrancy, without laying the proper groundwork to undergird inerrancy. As a result, the statement itself goes on for pages and pages in order to define that word “inerrancy,” with various caveats and conditions which can be difficult to follow.

In comparison, the Lausanne Covenant of 1974, authored primarily by the late John R. W. Stott, and strongly supported by the world famous evangelist of the 20th century, Billy Graham, gives a really brief definition of inerrancy, no more than a sentence:

“We affirm the divine inspiration, truthfulness and authority of both Old and New Testament Scriptures in their entirety as the only written word of God, without error in all that it affirms, and the only infallible rule of faith and practice.”

Short and sweet. The Bible is “without error in all that it affirms.” The “all that it affirms” part is left as it is because these are matters of interpretation.

These matters of interpretation are just as important as inerrancy itself. But upholding inerrancy and having a correct interpretation of every passage of Scripture is not the same. One can accept the doctrine of biblical inerrancy and still have errors in their interpretation of the Bible. Interestingly, most conservative evangelical churches that I know have a statement of faith which largely follows the very brief model of what we find in the Lausanne Covenant. Most people who would be inquiring about membership in a local church would probably fall asleep several times before trying to read all the way through the Chicago Statement.

I am glad we have the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy. Furthermore, the research that Michael Licona has given the reader in Jesus, Contradicted is in many ways fully in alignment with the Chicago Statement, as Dr. Licona himself argues. Those of us who live in a Western secularized culture who are concerned about the erosion of biblical authority owe a lot to those inerrancy architects of the 1970s. But frankly, looking back, sticking with the short and sweet Lausanne Covenant would probably have been the wiser move.

The irony behind this discussion is that even the principal authors of the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy did not agree among themselves and other signers of the document on some particular issues of Scriptural interpretation, and how they relate to inerrancy. The three principal authors of the Chicago Statement were Norman Geisler, J.I. Packer, and R.C. Sproul, all now deceased within the last decade. However, while all three authors firmly held to biblical inerrancy, as they defined it in the Chicago Statement, each of these three men had at times been under fire by other Christians for holding viewpoints which their critics claim undermine biblical inerrancy.

Norman Geisler believed that any belief in theistic evolution was going against biblical inerrancy. On the other hand, while J.I. Packer was not settled on the question of theistic evolution, he believed that one could hold to theistic evolution and still conform to the doctrine of biblical inerrancy. Nevertheless, Norman Geisler himself was quite friendly to the idea of an old earth approach to creation, affirming the standard date of a 4.5 billion year old earth. But there are many, many Young Earth Creationists who would say that Geisler had compromised on the doctrine of inerrancy because of his particular interpretation of Genesis.

R.C. Sproul was also in the same boat with Geisler, having affirmed Old Earth Creationism. But questions about R.C. Sproul’s commitment to inerrancy did not end there. R.C. Sproul did not accept the idea of a pretribulational rapture of the church, followed by a seven-year tribulation prior to Jesus’ final return. Nevertheless, there have been supporters of the Chicago Statement who have believed that any denial of a pretribulational rapture was a denial of or attack on biblical inerrancy! This just goes to demonstrate that while the doctrine of inerrancy is an important concept to consider and believe as evangelical Christians, at least in some sense, this is not the same as trying to figure out what is the most accurate and faithful interpretation of a passage or set of biblical passages one should have as a Christian.

The Jehovah’s Witnesses surely believe in the inerrancy of the Scriptures. However, they adopt certain interpretations of the Bible which are either heretical or downright dangerous. Jehovah’s Witnesses read what they consider to be an inerrant Bible to say that the doctrine of the Trinity is a human-made doctrine, and something not from God. They also believe that Acts 15 teaches that a genuine Christian should never get a blood transfusion, even if their life depends on it, simply because they think this is what their inerrant Bible tells them to believe.

The late singer/songwriter Prince, who converted to being a Jehovah’s Witness during his music career, died in 2016 of an accidental painkiller overdose, due to a condition which could have been prevented if he had elected to receive a blood transfusion for hip surgery, which he refused to take due to his Jehovah’s Witness’ interpretation of the Bible. In other words, just because someone believes in “biblical inerrancy” does not mean that this is a guarantee that someone will have an inerrant interpretation of the Bible, for every passage. In fact, certain misinterpretations of the Bible might prove deadly.

Another often overlooked aspect concerning the Chicago Statement is that it insists that inerrancy only applies to original autographs, which we no longer posses, and not to the Bibles we have in our hands today, as noted earlier in this book review. The irony of Michael Licona’s proposal is that for him, “biblical inerrancy” applies to both the original autographs AND the Bibles we have in our hands today. Licona argues for a form of biblical inerrancy which affirms that the Bibles we possess in our hands, smartphones, and laptops today are indeed the very inerrant word of God. Now that is something to celebrate!

Whether or not we need to revise the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy as Mike Licona proposes is a tricky prospect. It remains to be seen how well Mike Licona’s proposal will find acceptance. Even if Licona’s thesis is unconvincing to some in the final analysis, Jesus, Contradicted offers some excellent help for interpreting difficult passages in the Bible. I am not convinced by every particular interpretation Michael Licona takes on every particular passage. But no one needs to follow Licona’s analysis of each Bible passage in lock-step in order to find his overall thesis convincing and compelling. As Michael Licona closes out his book in the final chapters, the question of inspiration looms large.

A Better Doctrine of Inspiration Undergirds the Best Defense for the Inerrancy of Scripture

In Jesus, Contradicted, Michael Licona argues that the problem with the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy is that it is built on a deficient theology of inspiration. What does it mean to say that the Scriptures are “God-breathed,” as we read in 2 Timothy 3:16? Interestingly, both Michael Licona and the late Michael Heiser are in agreement here. As Michael Heiser put it, a more robust understanding of “inspiration” would suggest that the “God-breathed-ness” of Scripture has to do with the source or origin of the revelation, and not the process by which inspiration actually happens (see video below).

This distinction is vitally important. The vast majority of scholars today agree that the Bible was not orally dictated by God to the authors of the Bible, who simply transcribed down what God audibly told them to write. Sure, there are cases where God is reported to have given messages to an author audibly. But these cases are relatively rare across the entirety of the biblical canon.

The norm in the Bible seems to suggest that God has inspired the particular authors of Scripture to write what they wrote, by entrusting to them the message which God has desired to communicate to us. Any incidental details resulting from the process by which the authors actually wrote are not as important as the fundamental message entrusted to each Scriptural author. Any human element discovered in the phenomena of the text need not suggest that God is somehow lying to us, or otherwise deceiving us.

Nevertheless, God’s providence is such that God approves of every word we find in our sacred text.

Some critics have ironically charged that Michael Licona is denying the “verbal plenary inspiration” of the Bible. In this approach, verbal indicates that each word of Scripture is God-breathed, and not just the ideas behind the words Plenary means “complete or full”; when used to describe the inspiration of Scripture, in that all parts of the Bible are equally of divine origin and equally authoritative. Yet what critics might be missing is the main point behind what Michael Licona is arguing.

The other “Michael” I have referred to earlier is the late Old Testament scholar, Michael Heiser. In response to such critics, Michael Heiser rhetorically asks the question: “Why must we say God chose or gave the words?” Instead: “Why can we not say God was satisfied by the word decisions made by the people he chose?”

This is not to say that the Holy Spirit stands whispering behind the sacred author, saying something like, “Here, Paul, use this word next in your letter to the Romans…. Then after that, Paul, use this following word…. Then after that, close your sentence with….. ,” and so on. No, this is a flawed view of inspiration. It wrongly suggests that the Holy Spirit somehow puts the content of a Scriptural book into something like a spiritual memory bank, and then does a “divine download,” as Michael Heiser puts it, into the brain of the sacred writer, or else puts the sacred writer into a trance, where his pen is moving across the papyrus, without knowing what is going on. While this kind of mode of “inspiration” might fit what a New Age person thinks “inspiration” is, it is not suitable for a Christian.

It is better to view “verbal plenary inspiration” this other way, the way Michael Heiser (and Michael Licona) suggests, thinking about the process which flows from inspiration, as distinct from the inspired source itself, the inspired writer. That process stemming from the inspired source gives us the results which God approves, to the exact word, by God’s sovereign will. Does that not give us a better approach to verbal plenary inspiration?

Many Christians default to an oral dictation model more out of habit as opposed to studied reflection. The oral dictation theory belongs more to what Muslims believe about how the Koran was supposedly inspired by God. But with the New and Old Testaments, the process of how inspiration, as origin or source, is worked out is more complex. It remains a great mystery as to how the infallible God used fallible human authors to record for us the Word of God, as found in the Bible. Acknowledging this mystery in no way takes away from the origin of the Bible as being fully inspired by God. Michael Heiser says it well: “Our understanding of inspiration must be consistent with what the Bible is, by God’s choice, else we make it vulnerable to attack.” Both Michael Licona and Michael Heiser are on the right track here.

Why Inerrancy Is Still Important. But We Need a Better Definition of Inspiration to Support It

In his 1976 bombshell of a book, The Battle for the Bible: The Book That Rocked the Evangelical World, Harold Lindsell, who served as a professor at Fuller Theological Seminary (my alma mater) and who was former editor for Christianity Today magazine, wrote the book that originally threw my theological world into a tailspin by trying to convince me of a new theory of mathematics, that Peter’s “three” denials of Jesus were really six denials, according to an inerrantist reading of Scripture, as though 3 equals 6. The way Lindsell tried to make is argument in the nitty gritty details utterly and ultimately failed to convince me. But I am mindful of the conclusion to his book.

“It is true that a man can be a Christian without believing in inerrancy. But it is also true that down the road lie serious pitfalls into which such a denial leads. And even if this generation can forego inerrancy and remain more or less evangelical, history tells us that those who come after this generation will not do so. We have a responsibility for those who follow after us as well as for generations unborn” (Lindsell, p. 210)

My pastor back then in the 1980’s, Dick Woodward, at the Williamsburg Community Chapel, preached a few times referencing this book, as he wrestled with the arguments therein. Lindsell offers a slippery slope argument, which is frankly a logical fallacy. Nevertheless, some do fall down such slippery slopes, and the impact is generational.

Thankfully, Michael Licona sees this as a problem as well. The difference between Michael Licona and Harold Lindsell is that Licona offers a way through the impasse I hit when reading Lindsell’s book back in the early 1980s. Licona suggests that we rethink inerrancy through rebuilding its foundation by rethinking what inspiration really means. In my view, Michael Licona is fully in the right. May those of Michael Licona’s tribe increase.

If there is any substantial fault to be found in Jesus, Contradicted, it is that Michael Licona probably will not be able to convince everyone that a revision of the Chicago Statement is necessary, based on rethinking the concept of inspiration, which is a prerequisite to articulating a doctrine of inerrancy. Some folks will only continue to either play the ostrich and ignore the problem, or they will assume that Licona has some secret nefarious motive in wanting to revise the Chicago Statement. In lieu of that, the short and sweet definition of inerrancy articulated at the Lausanne Conference in 1974 is probably the best we are ever going to get.

Here is a clip from Michael Heiser’s teaching which echoes Licona’s thesis regarding the inspiration of Scripture:

- Let the Bible be what it is

- Let God’s choices of people be what they were

- Let providence rule the day

Our understanding of inspiration must be consistent with what the Bible is, by God’ choice, else we make it vulnerable to attack.

Here is great interview Sean McDowell has with Michael Licona about Jesus, Contradicted.

Some other interviews with Michael Licona can be found here, and here, and here with Frank Turek, and an interview with an atheist here.

Read here about other Veracity blog posts concerning inerrancy:

-

- Veracity blog founder John Paine on inerrancy and infallibility.

- Inerrancy Summits and the Valleys of Interpretation: all about maintaining the distinction between the inerrancy of Scripture versus the supposed inerrancy of someone’s interpretation of an inerrant Bible.

- Mustard and Chocolate: my own journey about the relationship between inerrancy and the interpretation of Scripture.

- Henry Morris and the Case of the Missing Signature: some historical background behind the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy.3

Notes:

1. We might very well have six denials of Jesus by Peter, if one tries to reconstruct the historical narrative. While Mark and Luke mentioned two cock crows, it is likely that both Matthew and John simplified and compressed the account into only one cock crow, judging that the exact number of cock crows was not a significant feature of the story, More than likely, the number “three” that all four Gospels mention regarding the denials of Jesus made by Peter is symbolic in nature, as opposed to being a hyper-literal description that must be harmonized with each different story told in our Gospels. What readily comes to mind is the Old Testament story in 1 Samuel 3 about the young boy and future prophet Samuel waking up three times at night to ask his mentor, Eli, what Eli wanted, thinking that Eli was calling out to him. It took three times, but Eli finally realized that it was the Lord who was speaking to Samuel. It is reasonable to suggest that the “three” times in the Gospels corresponds to Peter’s ultimate realization was that he had betrayed Jesus, despite his earlier protests that Peter would never deny Jesus. Are the incidental details of the story being changed to serve the artistic purposes of the different authors to highlight the character of Jesus, in contrast with Peter? Yes. Is this a rejection of inerrancy? No, unless one insists on a strict view of inerrancy which requires a number of exegetical backflips to arrive at the desired conclusion. ↩

2. Nerd alert: It is important to note that developing a robust theology of inspiration does not imply junking the concept of inspiration as some invention of the early church. In a brief appendix to Jesus, Contradicted, Michael Licona gives a review of a recent monograph, Poirier, John C.. The Invention of the Inspired Text : Philological Windows on the Theopneustia of Scripture. In Poirier’s book, the author contends that the Greek word “theopneuestia” found in 2 Timothy 3:16, typically translated as “God-breathed,” as in “all Scripture is God-breathed,” should be better translated as “life-giving.” Licona challenges that translation as being an inadequate representation of the theology of the early church. Poirier’s thesis is currently a talking point advanced by certain YouTube scholarly critics of historic orthodox Christianity in numerous “Tik-Tok”-like videos, so it is helpful that Michael Licona critically engages Poirer’s thesis.↩

3. For an introduction to Michael Licona’s thesis from a few years ago, take a look at this analysis of the death of Judas, one of the most perplexing discrepancies in the Bible. Finally, here is a link to my first blog post regarding differences in the Gospels, 11 years ago. ↩

July 24th, 2024 at 7:58 am

J. Warner Wallace on differences in the Gospels. This suggests that there could have been witnesses in the Gospels who misremembered certain details, while still being reliable. As with Michael Licona, this is yet another way of viewing inerrancy at odds with how Harold Lindsell argued for inerrancy in the 1970s. Wallace’s approach is fine, but it certain cases, I think Licona’s approach has more explanatory power:

LikeLike

May 19th, 2025 at 8:21 pm

More Michael Licona’s views on biblical inspiration:

LikeLike

July 2nd, 2025 at 10:25 am

In the past, I have recommended Alisa Childers’ resources on YouTube to others, but after several oddball interviews she has conducted over the last two years, I have serious doubts about her credibility. She means well, and there are some very good interviews, but in other cases it is pretty evident that she has not examined the data being discussed as thoroughly as she could. The recent interview she had with the Discovery Institute’s John West is pretty much in the same vein, failing to represent the views of others accurately, and setting up a straw men which can be easily knocked down.

In the following video, Mike Licona defends his genre identification of the Gospels as Greco-Roman bios against John West’s claim that Licona’s perspective is nothing more than early 20th century theological liberalism warmed over.

This claim is woefully misinformed, as for decades, probably extending back into the early 20th century, the Gospels have been characterized as being a part of their own unique “Gospel” literary genre, having no similarities to other know genres in the 1st century world. The research that substantiates Licona’s views have only been peer-reviewed published within the last 35 years, which shows that West’s claim is completely anachronistic. For if West is correct, we probably need to rethink the views of Scripture held by early church fathers like Augustine and Origen. That is a pretty gutsy perspective to hold:

LikeLike

July 8th, 2025 at 7:09 pm

From a tweet by Mike Licona:

“God-breathed doesn’t mean dictated. Theopneustos points to origin, not process.”

https://x.com/DrMikeLicona/status/1938350569745272996

“So, what does theopneustos—God-breathed—actually mean? The truth is, we’re not entirely sure. At a minimum, it indicates that something originates from God in some meaningful way—that He participated in it. But beyond that, we’re on shaky ground. When we look at 2 Timothy 3:16, it could mean more—but we simply don’t know for certain. That’s why I want to be careful. I’m a historian, and I try to stay within the limits of what the evidence supports. And in this case, I believe the safest conclusion is this: Scripture is divinely inspired, in that it ultimately derives from God who approve it—thus, it carries absolute authority.”

Augustine: “Even if the evangelists put different words in a person’s mouth, as long as the sense is preserved, there is no falsehood.”

https://x.com/DrMikeLicona/status/1937339238770507991

LikeLike

August 11th, 2025 at 1:46 pm

Found a helpful article from twelve years ago regarding inerrancy, the importance of how the term in defined. Ultimately, we must make an important distinction between “inerrancy” and the “interpretation” of Scripture. Belief in “inerrancy” does not guarantee the correct “interpretation” of Scripture. When some insist on “inerrancy” they are actually inclined to confuse the inerrancy of Scripture with the supposed inerrancy of their interpretation of Scripture. The two are not the same:

https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/justin-taylor/what-is-inerrancy-and-why-do-we-need-the-word-packer-and-frame/

LikeLike