How Vince Lombardi’s emphasis on the fundamentals can help Christian discipleship in our churches

Do you know what you believe as a Christian?

Growing up in a mainline Protestant denomination, I heard very little about what it meant to have a personal relationship with Jesus. It was not until my teenage experience in an evangelical youth ministry, that I learned about that.

However, I did go through a process called “confirmation,” in order to become a full member of the Episcopal Church. In those classes, I was required to memorize the Lord’s Prayer, the Ten Commandments, and the Apostles Creed. I never made the connection between memorizing a bunch of words and actually becoming or being a Christian. For years thereafter, I tended to dismiss such rudimentary training as meaningless, a rote memorization process, with an emphasis on doctrine over and against pure devotion to Christ.

But I have since rethought that negative assessment. Granted, my training as a youth was rather incomplete, but at least it was something. Even though many liberal Protestants undermine such training, by rejecting classic doctrines of the Christian faith, at least such training was there, in the liberal Protestant tradition. Even in other traditions, such as in Roman Catholicism, there has been a revival in recent decades to emphasize educating, not just children, but adults as well, in basic rudiments of the Christian faith. In order to become an adult member of the Roman Catholic Church, you are required to attend several months of classes, known as the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults (RCIA). Some of these classes can last a year, or more!

Now, compare that to what you typically find in an evangelical Protestant church (of course, there are exceptions here). Let us say that you come to a new church, and you make it through the first few weeks of visits. You might be asked to consider joining a small group Bible study. Some might be encouraged to become a “member” of that church. But what is involved with that? In many cases, the process to become a member is quite easy: Just share your testimony, read the statement of faith (assuming there is one), and talk to the church leaders, to see if you might have any questions about that statement of faith. Sign on the dotted line, and you are in. In just a matter of weeks. Easy-peazy.

A Brief History of Catechesis in the Church

Compare that to what was typical in the early years of the Christian movement, the period of explosive growth in Christianity from about the 2nd to the 5th centuries. Candidates for Christian baptism would often go through an instructional process, that could last up to three years, before a newly professed believer would be accepted for baptism. This instructional process has been called catechesis, which originally meant “oral instruction” in the faith. Such rigorous catechesis was necessary because so many of those early believers came from very diverse backgrounds, and often lacked basic knowledge of the Bible.

During the Middle Ages, the practice of catechesis tended to fall out of favor. After all, nearly “everyone” in those days professed to be a Christian. Having Christianity as the established religion of the Roman Empire made that pretty easy. But by the time we get to the Protestant Reformation, the need for catechesis was so overwhelming, it could not be ignored. In a letter to a Protestant colleague in England, in 1548, the great French/Swiss reformer John Calvin remarked, “Believe me, Monseigneur, the Church of God will never be preserved without catechesis.” Different catechesis traditions were developed, to train up believers in the faith, such as the Heidelberg Catechism and later, the Westminster Catechism. The success of the Protestant evangelical movement, led by a comparatively small consortium of Reformer intellectuals and pastors, like Luther and Calvin, was fueled by the consistent application of catechesis methods, to train the congregational masses.

But as J. I. Packer and Gary A. Parrett (a former student of Packer’s) write in Grounded in the Gospel: Building Believers the Old-Fashioned Way, the practice of catechesis in Protestant evangelical churches has suffered a serious decline over the past century. Part of the reason why catechesis has dropped off the radar, for many evangelical churches, is due to conflicting catechesis methods and teachings.

Different catechesis content has been associated with “denominationalism.” So, because nearly every denomination has their own “pet doctrines,” that they like to promote, the reaction in some interdenominational or non-denominational settings is to reject the whole project of catechesis altogether, and try to keep everybody from arguing with one another all of the time. We avoid doctrinal disputation, because it might come across as sounding “unloving.”

In place of catechesis, many evangelical churches have simply substituted in the telling of Bible stories, especially in teaching children, as a supposedly safe way of avoiding doctrinal controversy. The sad irony about this is that the Christian faith has witnessed its greatest decline during this same time period, when catechesis has fallen out of favor. It is as though the contemporary evangelical church has come close to the theological shallowness of the late medieval church, that precipitated the crisis of the Protestant Reformation, in the early 16th century.

History has an odd way of repeating itself.

I know of pastors who metaphorically wring their hands, wrestling with the fact that so many church members are not out there sharing their faith, and serving for Christ in their community. Some pastors assume that their church membership knows a lot, but that they do not do much with their faith. Perhaps if folks join small groups, or get involved in various other activities in the church, they might be compelled to put their faith in action more.

Not every pastor’s grief is like this, but it is a common narrative, in some circles. I share the same concern, but I do not buy into the narrative that assumes that church members know a lot, but just are not doing enough. Rather, we have it backwards. Christian are not doing enough, because they do not know why they believe what they believe.

I should clarify here. It is very tempting then to think that the lack of knowing why Christians believe certain things is the fundamental problem. The area of knowing why you believe what you believe is the task of apologetics. We need to do better at this, surely. But apologetics is not the fundamental problem. A more fundamental problem is that many Christians in our churches simply do not know what they believe… or at least, the experience of learning to know what they believe is uneven, in many churches today. Correcting the problem of helping Christians to know what they believe is the task of catechesis.

Some churches have great education programs, but not everyone participates in such programs. Many Christians are involved in great small groups, where they are being challenged to grow more and more in their faith. But many other Christians have no such small group experience, or they are involved in small groups that really do not help them go deeper in their faith. In other words, the catechesis experience in many contemporary evangelical churches is uneven, at best.

So, what is the answer then? To put it bluntly, churches need to commit themselves to the process of training Christians, across all ages and categories of church involvement, in the rudiments of the faith, on a continual basis. Or, at the very least, some type of catechesis training is necessary for becoming church members. Great sermons, great small groups, and great Christian education classes (like Sunday School) will surely help, but a more fundamental approach is necessary.

How Vince Lombardi Can Help the Church Get Her Priorities Straight

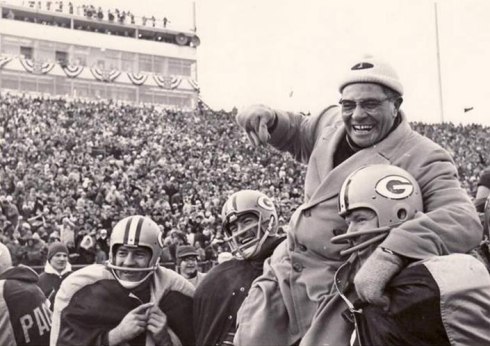

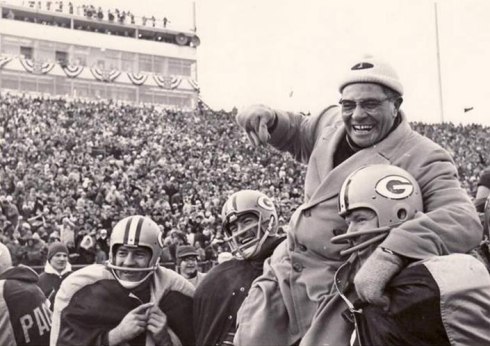

An analogy might help here. What made the Green Bay Packers, of the early 1960s, one of the greatest teams in the history of American professional football? It all came down to how their coach, Vince Lombardi, emphasized the fundamentals. In the summer of 1961, Lombardi had just coached a group of seasoned veterans, to nearly win the championship, which they had just narrowly lost. But Lombardi would not assume that his experienced players knew everything. He started at the beginning, with the fundamentals. He famously gathered his team together, for training camp, and held up a pigskin in his right hand and said, “Gentlemen, this is a football.”

A few of the players snickered at Lombardi. After all, they all knew what football was all about. They were all professional football players! But Lombardi persisted, and he emphasized the basics of blocking and tackling. By the end of the season, the Packers beat the New York Giants 37-0, to win the championship. Lombardi would go onto lead the Green Bay Packers in a long stream of championship victories, throughout the 1960s.

The analogy should be clear. We should not assume that church members know what they believe. Instead, as part of the membership process and/or even something incorporated into the foundational practices of the church, evangelical churches should institute a catechesis, to help believers better understand the basics of the faith.

A Couple of Objections to Catechesis

Let me address a few important objections to the practice of catechesis. First, some do not like the idea of catechesis because it sounds like doing something in a ritualistic fashion. Some Protestants might take this a step further and complain that catechesis sounds a bit “too Catholic.” But simply reciting a question and answer does not necessarily imply saying something purely for the sake of memorizing it. Rather it is meant to stimulate thinking: When I say that I am a Christian, what does that exactly entail? When I say I believe in Jesus, what does that really mean? To ponder the depths of our faith is meant to ground us in a Gospel way of thinking. As to the complaint of it being “too Catholic,” we should bear in mind the possibility that this is an area where Roman Catholics have much to teach those Protestants, who have an aversion to contemplating sound doctrine.

Secondly, some do not like using a catechism as it tends to focus on telling people what to think as opposed to how to think. That is a good point, but catechesis need not be used that way. Instead, a better use of a catechism would be to create a springboard to further discussion. Most catechisms aim at being pithy and simple, mainly to make them more acceptable for use with children. But pithy and simple need not discourage more thoughtful reflection. Instead, a good catechism should include resources, such as passages of Scripture, that can be looked up to see how well the catechism lines up with what the Bible actually says. No catechism is 100% perfect. But if they lead the Christian to have a greater knowledge and confidence in what they believe, then the effort of learning a catechism becomes worth it.

Practical Suggestions for Catechesis in the Church

There are three practical suggestions to make here, to move forward in the area of catechisis. First, it would be to read Packer and Parrett’s Grounded in the Gospel: Building Believers the Old-Fashioned Way. J . I. Packer is one of the great statesmen of the contemporary evangelical movement. In the Grounded in the Gospel, one of Packers’ last books, written in 2010, Packer along with Parrett, lay out the need for evangelical churches to revive the practice of catechesis, and offer some help in trying to navigate what that would look like in the everyday life of the church.

I find it significant, that in the waning years of Packer’s life, now that he is essentially blind, and no longer able to read and write books, that he would, after looking back on decades of service to the church, challenge evangelical churches to reconsider catechesis, as the means by which a local church, over the long haul, can reinvigorate its ministry and outreach into their community. In Grounded in the Gospel, the chapter on the history of how catechesis was conducted by the early church, as well as during the early years of the Reformation, makes the book particularly challenging and helpful.

Secondly, here might be a good way to help churches out, when going through the process of becoming a member of a church: Require that prospective members obtain a sponsor. The early church adopted the practice of having a baptized, mature Christian adopt a prospective candidate for baptism, as a type of sponsor. The advantage of having a sponsor is two-fold: (1) It is less burdensome for those reviewing candidates for membership, such as elders and/or pastors in the church, to always be responsible for every aspect of catechesis. Having another church member vouch for a membership candidate’s testimony, and their knowledge of basic Christian doctrine, helps to distribute the load in the catechesis process. (2) It is less intimidating, when a church membership candidate comes before a group of elders/pastors, to have a friend and sponsor accompany them, if they so request. Having a sponsor should not necessarily assume a long term commitment. But it can help the prospective new member become more integrated into the warmth and life of the community.

Thirdly, what would be a good example of catechesis, for the contemporary evangelical church? Specifically, what about a catechesis for an interdenominational church, where confessional differences, over non-essential matters of the faith, are honored and respected? I would suggest a good look at the New City Catechism, developed by Redeemer Presbyterian Church, under the sound leadership of Pastor Timothy Keller. Keller started one of the most dynamic and growing churches in New York City, and he and others took some older catechisms and modified them for contemporary use, which can be incorporated into growing churches.

There are several things I really like about the New City Catechism. First, the catechism is broken down into 52 question and answer sections, which could easily be inserted into a weekly worship service, with the cycle to be repeated every year. Read a question, and its answer, as a congregation, and that is it. A pastor friend of mine uses the New City Catechism in their weekly worship services, and each Q&A lesson only lasts a couple of minutes.

That may not seem like a significantly impactful chunk of time, per service, but that is the point. A lot of churches are hesitant to add something new into the weekly worship service, because of other priorities. But inserting a 2-3 minute segment into the weekly worship service, dedicated to catechesis for the whole church, adults and children, is a reasonable way of approaching catechesis, without becoming unnecessarily burdensome. However, the long term benefit is what should be aimed for, for if you do these 2-3 minute segments every week, year after year, you are reinforcing a model of Christian instruction, that should pay off, over the long haul, with an increased vision for Christian discipleship, throughout the whole congregation.

The other thing I like about the New City Catechism is that there are excellent resources available to go deeper, for each Q&A section. The Gospel Coalition has audio resources, including a “children’s mode,” a shortened, even simpler version of the catechism, which is very useful. Furthermore, Kathy Keller, wife of Timothy Keller, has an excellent introduction. Want videos? The New City Catechism website has them as well.

What is there not to like about the New City Catechism? Well, for some, a few things … perhaps. As a minor point, the name “New City” has an urban flavor to it that might not ring well for non-urbanites. But more substantially, the New City Catechism is a trimmed down, more ecumenically appealing version of the Westminster or Heidelberg Catechisms. In other words, there is at least a modest emphasis on certain Reformed teachings, in the New City Catechism, that may rub some evangelicals the wrong way.

But such criticism misses the point of what something like the New City Catechism is meant to achieve. Instead of being a mechanism that stops conversation, the aim is quite the opposite. Rather, it is an invitation to further discussion and inquiry. There is enough breadth in many of the answers, involving possibly controversial topics, that it is only natural for catechism readers to begin to ask questions, which hopefully will encourage them to spend more time in Scripture, to dig out out more nuanced, detailed answers, that simply can not be summed up in a pithy Q&A collection like this.

For example, in question 25, “Does Christ’s Death Mean All Our Sins Can Be Forgiven?,” the language of “imputation” is used in the answer, which might puzzle those who favor more the “New Perspective on Paul” (assuming someone even knows what that is!!). But there need not be an either/or dichotomy here, as indicated by how the answer is framed: “Yes, because Christ’s death on the cross fully paid the penalty for our sin, God graciously imputes Christ’s righteousness to us as if it were our own and will remember our sins no more.” That peculiar word “imputes” is used here, but it is not expansively defined. The answer does not dig into the more technical aspect of imputing Christ’s active obedience vs. His passive obedience. Rather, the answer offers an invitation to further discussion, without straying from orthodox belief (SIDE NOTE: Grounded in the Gospel has a very balanced discussion of this particular “hot” theological topic, in our day, and its relationship to catechesis).

Here is one more example: In question 28, “What Happens After Death to Those Not United to Christ by Faith?,” the answer attempts to summarize various Scriptural ideas about hell. Christians today wrestle with the nature of hell; for example, is it a place of conscious eternal torment, or a place where the wicked will be eventually annihilated? A short answer might not seem nuanced enough. But the language of the answer creates a sense of wonder: “At the day of judgment they will receive the fearful but just sentence of condemnation pronounced against them. They will be cast out from the favorable presence of God, into hell, to be justly and grievously punished, forever.” How are all of these various phrases tied together? What does each one mean, in particular? Again, here is an opportunity to dig into the various Scripture passages referenced by the question, which serves as an invitation for further discussion.

On the other side, long time users of catechism many not like the New City Catechism, as it may not be Reformed enough for them. Sticking with something like the Heidelberg Catechism, would probably be better. London pastor Andrew Wilson, one of my favorite Bible teachers, blogged through the 52 weeks of the Heidelberg Catechism a few years ago, and I find his short reflections exceedingly helpful. Each one can be read in just a couple of minutes each. (Wilson wisely omits the sadly controversial question 80, that was inserted after the catechism was originally devised).

But the target audience for something like the New City Catechism is for those Christians who have no clue as to what catechesis even is. Of course, a church can simply branch out and develop their own catechism, that fits the needs of their particular congregation.

The downside to doing this is that you are pretty much trying to reinvent the wheel. Tim Keller’s church planting efforts show that the New City Catechism, which has been around for almost a decade, is an effective, low-impact tool for training a congregation in the basics of the Christian faith. Whether or not a church uses an already defined catechism, or creates their own, the point is that every church should have a means of instructing their membership, on the basics of the faith.

Making the Long Term Investment in Catechesis, For the Health of the Church

Implementing some type of catechism is desperately needed in our churches today. It is not just for children. It is for adults, too. At the very least, catechesis needs to be an integral part for becoming a member of a local church. The process of catechesis is designed to address systemic issues in the educational efforts of a local church, where basic knowledge of the Christian faith is typically not uniformly present, across the whole church body. Read Packer and Parrett’s Grounded in the Gospel: Building Believers the Old-Fashioned Way. Spend some time going through the New City Catechism.

The irony here is that our increasingly post-Christian world is looking a whole lot like the world of the early church, in those critical first few centuries. Religious pluralism is just as rampant today as it was in the period of the early church. The misunderstanding of Christianity, and even moments of persecution of Christians, mark our world today, just as it did in the early church world. However, today’s evangelical church has not picked up on the critical lesson of the importance of catechesis. We do not necessarily need a full three years of catechism training for receiving baptism, as the early church frequently did. But we do need something.

One final thought: some Christians are hesitant about catechesis, because they fear that an emphasis on doctrine will undercut our love for one another. But a word from the Apostle Paul should remind us that sound doctrine and genuine, loving Christian fellowship go hand in hand, as we go about “abounding in thanksgiving“:

- Therefore, as you received Christ Jesus the Lord, so walk in him, rooted and built up in him and established in the faith, just as you were taught (edidachthēte: sharing the same root as catechesis), abounding in thanksgiving (Colossians 2:6-7 ESV).

Take a lesson from Coach Vince Lombardi.

What is your church doing in the area of catechesis?