I play soccer with a group of friends at the College of William and Mary, where I work as an IT staff person. At the end of one of our games, we were talking about the upcoming visit by the Dalai Lama to speak at William and Mary Hall, on Wednesday, October 10. There were several jokes about strange Eastern religious customs and how hot it would be to wear a monk robe all day long. One made a sly remark about attaining “enlightenment” from the marijuana fumes rising up from the crowded Kaplan Arena this coming Wednesday from smuggled-in contraband. This is a big deal event for the College, with several thousand tickets sold out within minutes to hear the venerable representative of international Buddhism. So what is the big deal about the Dalai Lama?

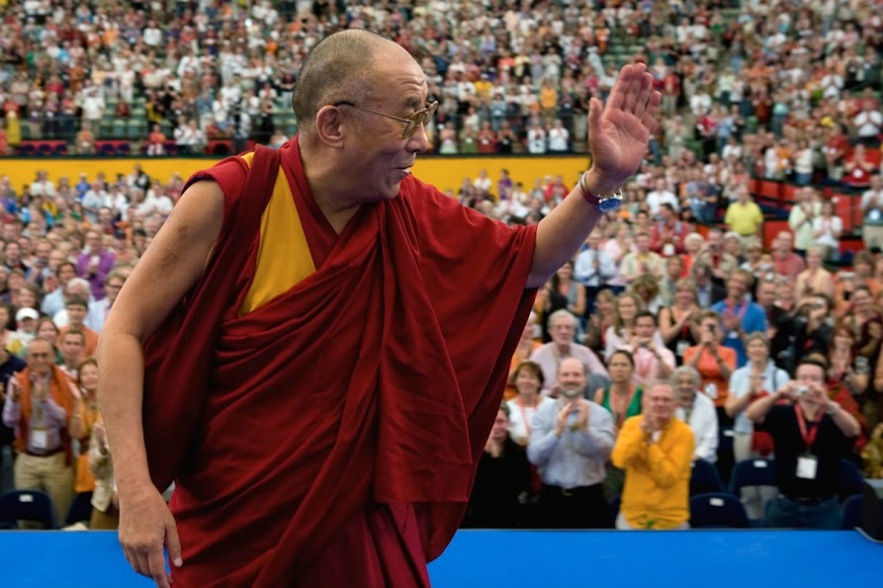

The 14th Dalai Lama

Actually, Tenzin Gyatso is the 14th reincarnation of the Dalai Lama, according to Tibetan Buddhist tradition. For hundreds of years, an unbroken line of spiritual teachers in Tibet have instructed the Buddhist faithful. But the Dalai Lama is more than a religious leader position, it is also a political role, unifying all of the Tibetan region north of the Himalayan mountains in Asia. So when Communist China invaded Tibet in 1950, it put the current Dalai Lama into a difficult situation. After a failed uprising against the Chinese in 1959, the 14th Dalai Lama fled and established a government in exile in India. The United States government has at times given support to the Dalai Lama’s efforts on behalf of the Tibetan people during the past fifty years.

Over those years, the exiled Dalai Lama has served as an international ambassador in the West for Buddhism. There are Four Noble Truths of Buddhism: (1) all of life is suffering, (2) all human desire leads to suffering, (3) the annihilation of desire releases us from suffering, which is enlightenment, and (4) there is an Eightfold path to that enlightenment; that is, right view, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration. Buddhism, however, is not a monolithic movement. The Dalai Lama represents part of the Mahāyāna tradition. But the most popular form of Buddhism in the West is a more concentrated variant, Zen Buddhism, first propagated largely by the famous Japanese philosopher, D. T. Suzuki, in the early to mid-20th century. Oddly enough, Buddhism is considered by many to be a “religion” but the more philosophical traditions are technically atheistic. Even so, there are syncretic flavors that combine animistic beliefs with traditional Buddhist philosophy. The study of Buddhism can get very complicated very quickly.

The Dalai Lama is almost like a “rock star” in the religious world, drawing large crowds wherever he goes. He has been a strong advocate for “Buddhist-Christian” dialogue. He has visited many Christian communities throughout the world, remarking on the many similarities between Buddhist and Christian practice, particularly in the realm of “spiritual disciplines”, such as meditation. The Dalai Lama has said that you can go to many Christian monasteries in the world and they use pretty much the same type of meditation techniques that you will find in Buddhist monasteries. However, the Dalai Lama also says that the philosophies behind Buddhism and Christianity are very, very different. Nevertheless, he optimistically believes that there is a way to reconcile these differences philosophically.

Has His Holiness rightly understood the relationship between Buddhism and Christianity? Vishal Mangalwadi, an Indian Christian theologian, has written extensively about his native Hinduism, but since Buddhism has its roots in Indian culture there are profound similarities. Mangalwadi argues that the fundamental difference between the Eastern faiths and Christian faith is more than simply philosophical. Comparing Buddhism and Christianity is like comparing apples and oranges. These different faiths address different problems and likewise offer different solutions. Mangalwadi suggests that while religions like Buddhism and Hinduism look at the problem of salvation as a metaphysical problem, the message of Christ approaches it is a moral problem. To put it differently, one way considers salvation fundamentally as a question of correcting false views of reality. The other way approaches it fundamentally as a question of mending broken relationships, particularly in addressing and healing human alienation from the Creator.

So why does the message of the Dalai Lama draw so many people? One thought is this: many people have grown up in our churches today but never really experience the reality of knowing Jesus. They have never meditated on the love and beauty of the Saviour, and they never find themselves drawn into that tender and intimate place of knowing the One who suffered for us, the One who shares in the depths of our alienation from the Creator who longs to embrace us. Instead, there are many who have found our churches or their own inward life to be spiritually vacant and so they look to “the East.”

The famous Hollywood actor, Brad Pitt, has a story like this. Brad Pitt once grew up in an evangelical church home in Missouri. In several interviews, Pitt laments that he found his Christian upbringing “very stifling”. One of the highlights of Pitt’s film career was his lead role in the 1997 film, “Seven Years in Tibet”, a movie where a much younger Dalai Lama plays a prominent spiritual role in helping to transform Pitt’s film character.

Raised a Baptist – Now a Buddhist

This is an important insight to have in our apologetics. It is very easy for a Christian to quickly dismiss an interest in Buddhism or other Eastern faiths as esoteric at best or even demonic at worst. Often our effort to reach our neighbor with the Gospel needs to recognize that if someone is drawn to look into Buddhism that there is probably a real sincerity to experience God, but that such a spiritual quest is perhaps misdirected. It takes great patience and humility to gently show such a person the path towards Christ.

If you meet a “fan” of the Dalai Lama who appears confused about the Christian faith, you could ask why that person finds the Dalai Lama so intriguing? If someone you know has made a study of Buddhism, ask them to tell you what they have learned. Perhaps the most attractive quality of Buddhist meditation is that many practitioners find meditation to be very therapeutic. It makes people feel better. Since Christians know that Jesus is the “Great Physician”, it is difficult to find fault with this. Furthermore, many Christians discover that there is a wealth of “spiritual disciplines” already within biblical faith that are therapeutic as well. Scripture meditation (Psalm 1:2), scripture memorization (Psalm 119:11), fasting (Matthew 4:1-4), and contemplative prayer (1 Corinthians 14:15) are prime examples. One does not need to look to “the East” to find a spirituality that heals. If Christians have a concern about the legitimacy of some spiritual discipline that “sounds Eastern”, they should have the confidence to know that God has given us His Word to guide us in all manners of spiritual growth and keep us on the right path (2 Timothy 3:16-17).

Apologetics isn’t simply about having the “right answers”. It is also about experiencing a rich and deep encounter with Christ that you can share with others. Nevertheless, the bottom line in our conversations with the Eastern seeker is not whether Buddhism is therapeutic or not, but is it True? Is Truth primarily a form of spiritual discipline or a philosophy, or is Truth a Person? Is Truth about having a spiritual experience as an end in and of itself, or is Truth about relating to the God behind that experience? A biblically-informed Christian knows that the answer is the latter.

Ultimately, the Gospel requires someone to come to Christ in a spirit of confession and repentance. But that spirit must begin with us. If we are not able to come to Jesus in confession and repentance and know the God who forgives us, it will be extremely difficult to persuade the Eastern seeker to come to the foot of the Cross. Are we the sweet aroma of Christ to those whom God is using us to reach (II Corinthians 2:15)?

Thomas Merton, a Trappist monk, corresponded with D. T. Suzuki in the mid-20th century. Merton was considered to be the most important interpreter of Zen Buddhism to a Western audience aside from Suzuki himself.

A good resource to help Christians understand the challenges of Eastern Religions in general is Ravi Zacharias, the Indian apologist who visited the Williamsburg Community Chapel several years ago. Ravi’s book Jesus Among Other Gods has been used in several Vine Life classes at the Chapel, along with an accompanying set of videos available in the Chapel Resource Center: Ravi Zacharias International Ministries

A good readable introduction to Zen Buddhism in particular is Thomas Merton’s Zen and the Birds of Appetite.

If you want the really advanced stuff and like listening to MP3s, search on the web for Ellis Potter. Potter is an Ex-Zen Buddhist who formerly worked at L’abri Fellowship in Switzerland: Ellis Potter MP3 Resources/

The College of William and Mary is planning to stream the Dalai Lama’s visit live beginning at 2pm on Wednesday, October 10 from http://www.wm.edu/sites/dalailamavisit/

On Veracity, we have a series of blog posts that cover the issue of religious pluralism in general from the perspective of doing Christian apologetics. If you are intrigued by what you read here, the arguments are spelled out in more detail in #1, #2, #3, and #4.

October 8th, 2012 at 6:52 am

Clarke, thanks again for such a well-researched and informative post!

LikeLike

October 8th, 2012 at 8:13 am

very interesting and insightful! thanks for posting.

LikeLike

October 8th, 2012 at 10:04 am

Still up in air will let u know

Jim Shaw MD

Co-founder

Lackey Free Clinic

Yorktown VA

LikeLike

October 10th, 2012 at 5:12 pm

Just a couple of observations about the Dalai Lama’s talk this afternoon at William and Mary…..

The Dalai Lama was in exquisite form with his warm and intelligent personality. He is really a likable man. Fortunately, he had an interpreter with him who helped him out with his English, as sometimes his Asian accent made it hard to follow at times. He donned his traditional Tibetan monk robe with a William and Mary visor on his head.

One of my colleagues remarked that he reminds you of the Yoda character in the Star Wars movies. Since the Star Wars films are basically a set of tracts for Eastern religious philosophy, I thought this was an apt description.

He spoke on many topics, but the general theme throughout was the need for continued inter-religious dialogue and understanding. This is to be commended greatly, but it is important to note the framework for how he set this. His approach is very consistent with his Buddhist faith but not so much with respect to a biblical way of thinking.

For example, when asked the question as to how a non-Buddhist can appropriate the life and work of Siddhartha Guatama (the original Buddha), he responded by saying that those who grow up in a Judeo-Christian tradition should remain in that tradition. If you grow up in a Christian home, you should remain a Christian and integrate the example of the original Buddha as appropriate into your own faith. But the rationale for this is that staying in your own faith community throughout your life causes less problems. His Holiness never really addressed the question of Truth. So adherence to a particular faith tradition based on whether it is True or not is not something that His Holiness addressed.

When speaking of Jesus in particular, His Holiness speculated on what took place in Jesus’ life after early adolescence but prior to his public ministry. Granted, the New Testament is silent about this period. His Holiness suggested the possibility that Jesus may have traveled to India during this time. I have heard this speculation argued in a more forceful way by a number of New Age type folks. But it should be stressed there is not a single shred of evidence to support this claim. But if such a claim were true it would lend support to the Dalai Lama’s additional claim that India is the model nation for understanding and celebrating the world religions in all of their diversity. As India was the birthplace of Buddhism, this is consistent with the message of His Holiness.

All in all, the speech given by His Holiness was a measure of Tibetan Buddhism in its most appealing, charitable and articulate form. However, while there were surely things a Christian can agree with that were said, it must be emphasized that the Bible has a very different take on these topics. The study of God’s Word is the best tool we have as Christians to address these type of concerns and proclaim the Good News of Jesus.

William and Mary currently has an archived copy of the Dalai Lama’s talk available at http://www.ustream.tv/recorded/26051223. You might want to skip through the choir introduction …. it was … let’s say … a little bit peculiar.

Clarke Morledge

LikeLike

October 10th, 2012 at 5:47 pm

Thanks Clarke for the update and for the thorough research. A number of people have told me emphatically how much they have enjoyed your posts.

LikeLike

October 12th, 2012 at 11:18 am

One other followup here: if anyone thinks there is any credibility to the claim that Jesus spent his “lost years” traveling to India where he learned to become something roughly equivalent to a modern “Zen master” Buddhist, he should read Bart Ehrman on this.

It is very tempting to pull out an ad hominem argument that only Christians would deny Jesus’ Hindu/Buddhist connection to India. But Ehrman is an agnostic and acknowledged critic of evangelical faith. His historical research from _Forged: Writing in the Name of God — Why the Bible’s Authors Are Not Who We Think They Are_ (pp. 282-283) makes the point that the whole “Jesus in India” legend was a hoax propagated in the late 19th century.

Just a note — Ehrman’s anti-evangelical bias is troubling in other areas, but he is probably one of the top historians and textual scholars of early Christianity living today.

See this link for more details: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lost_years_of_Jesus

We need to base our faith on facts, not hoaxes.

Clarke Morledge

LikeLike

October 15th, 2012 at 2:21 pm

Your follow-up highlights a really interesting reality–we don’t have to agree with everything a person thinks, says, or writes to be able to draw useful material for our own conclusions and positions. Bart Ehrman is not going to make anyone’s top 10 apologists list, but even in such a skeptic we can find useful scholarship.

LikeLike

February 25th, 2013 at 8:13 pm

Just remember that an approach to question Buddhists about their systems and techniques need to be done using reason, logic, and examples, not scripture. The first rule in any debate is to agree upon the common authorities. Christians almost always argue using the Bible as the only authority; Buddhists, obviously, will not accept the Bible as an authority (except perhaps, like H. H. the Dalai Lama sometimes does, to show how similar teachings are expounded in certain cases).

A good Buddhist practitioner has an uninterrupted tradition of debate for 2,600 years, which climaxed around 400-1100 CE, but was never truly lost. When engaging in debate, Buddhists will argue mostly with logic/reasoning, giving examples or analogies, and, if they are arguing with other Buddhists, they will also resort to scripture, to show they’re not inventing anything. But during all those centuries, Buddhism has come in contact with several religions and philosophies where arguing based on scripture is not possible; even different Buddhist schools will not agree on all texts. So they have a strong training in arguing only with logic and example.

Putting this in perspective with a simple example: when arguing why Christians can put all their faith in Jesus about the road to salvation, Christians will either use the Bible as a source, or possibly a religious book written by a Christian author, or even a comment made by a Christian priest, theologian, or community leader. These are all arguments based on authority, but an authority that no Buddhist will recognise or accept (“This is true because Jesus said so; and what Jesus said is in the Bible; and the Bible is true because it was inspired by God; Jesus is God” — circular argument based on authority).

In the debate with a Buddhist, you will have to forfeit all your references to authorities, and just work using logic, reasoning and examples, because that’s what a Buddhist debater will also do. You can, for instance, claim that Siddharta Gautama never existed, that his teachings are all false, and agree with the Buddhist debater not to mention them. Will they still make a valid point?

Of course they will. The whole point of the Buddhist training is that you can reach results by following it. It matters little if Siddharta existed or not, or if his teachings were really given by him. What matters to a Buddhist is if the methods work and if you can attain the results described in them. And this, I’m afraid, is what every serious Buddhist practitioner will experience if they follow Siddharta’s methods, no matter what. Even in our days, people reach the same level of realization that Siddharta did, 2,600 years ago, and this can be captured on videos and cameras and measured by scientific equipment and independently validated.

By contrast, Christians have to take for granted that Jesus did not lie and that by completely putting one’s trust in Jesus, you will be saved. The point is, you cannot be sure until you die — nobody has come back to report on success.

Buddhists, on the other hand, do that all the time.

Another point worth mentioning: most religions, and Christianity is no exception, spend 90% of the time explaining what they claim to be the Truth, and 10% in describing methods on how to achieve the Truth. Buddhism is all about the methods. There are just a few guidelines to allow you to recognize the result when you finally achieve it. So asking a Buddhist “what is, for you, the Truth?” they will very likely just ask you to open your eyes and see what’s around you — you don’t need elaborate philosophical discussions for that.

Buddhism is also not about “therapy” in the sense of “feeling well” or anything like that; anyone claiming that they meditate just because “they feel well” about it are not truly Siddharta’s followers. Sure, some meditation techniques might give one a feeling of well-being — but so does getting immersed in a foam bath listening to relaxing music. And it’s far easier! To achieve just a tiny spark of what Siddharta intended takes perhaps 10,000 hours of meditation using a qualified teacher (and not some instructions read on a website or on a book); it’s hard work! This is the main reason why very few practitioners don’t get many results — they’re just not being diligent enough in their practice. Buddhism is the spiritual equivalent of becoming an Olympic-class athlete — it requires a lot of intense training, all the time. And even if you achieve that level, it’s not enough: you’re running for the gold. That takes even more time and practice.

Obviously, the vast majority of Buddhists will know actually very little of what their methods are good for, or what they can ultimately achieve with them. Most will have just a very basic understanding but no clear idea about what they’re doing. This is more true in the East, where Buddhism is a cultural phenomenon, but even in the West, the attraction to Buddhism might just be a form of rejecting the established culture and “shopping around” for alternatives. Don’t even take for granted that someone claiming to be a Buddhist monk (or even a teacher!) is qualified to engage in a meaningful debate: most will be able to repeat some things they’ve heard but not truly understand them.

By contrast, someone who is deeply engaged in their Buddhist practice and who has an adequate knowledge of what they’re doing and why will be very good in debating, and start to raise doubts in the Christian’s questioning mind. This is the major reason why Buddhists don’t proselytise: most serious spiritual paths require an amount of faith and reliance upon certain “truths” to work at the moment of death, when it’s too late to do anything else but have full confidence in the path one has followed throughout their lives. Any shadow of doubt at that moment can be fatal. To prevent this, people like H. H. the Dalai Lama just begs for Christians to remain good Christians throughout their lives and not “mix” and “confuse” things with other faiths — which, at the moment of death, will just raise doubts, and become a source of anxiety. By contrast, a good Christian (or Muslim, or Jew…) will have absolutely no fear at the moment of death and will have a peaceful mind, certain that they did the best of what was expected of them.

I think that this is the main reason why H. H. the Dalai Lama is so fond of inter-religious discussions. He wants to make sure they remain good believers in their own faith, since that’s what will benefit them most. And one of the Dalai Lama’s vows is to benefit as most sentient beings as he possible can — not by “confusing” them, or trying to undermine their confidence or faith, but rather the opposite: by telling them that their view is similar (even if it’s not the same) and they’re far better off if they follow the view of the religion they already have, instead of mixing and confusing things and questioning their own faith.

LikeLike

February 26th, 2013 at 8:58 am

Gwyneth,

Thanks for taking the time in writing such a thoughtful and detailed response. This is great!

I wish I could address all of your points, but my wife says I spend too much time on the blog, so alas, I must be brief in interacting with comments. I would like to challenge you on a few things and see what you think.

First, you comment that “in the debate with a Buddhist, you will have to forfeit all your references to authorities, and just work using logic, reasoning and examples, because that’s what a Buddhist debater will also do.” I would contend that Buddhism still has reference to authority, but unlike the Christian message where the locus of authority is found in the person of Jesus Christ, as articulated in the Christian scriptures, the locus of authority in Buddhism is found within the experience of the Buddhist, including the individual’s logic, reasoning and examples, as articulated within the Buddhist scriptures. Perhaps this is a bit overstated, but in one case the authority is external (Christianity, based on revelation) and in the other it is internal (Buddhism, based on disciplined self-reflection). How does that sound?

Your argument that the relationship between Jesus and the Bible as a circular argument requires a more thoughtful engagement than I can give currently. Unfortunately, even though some Christians present it this way, it is not accurate. Here on Veracity, both John and I would NOT argue with circularity that we believe the Bible to be true because the Bible says it is true. Instead, we would say that the Bible is true because it is true. There is a big difference. We always start with Jesus Christ, who gives us the Bible as our authority. But the Bible serves as a way to verify that what we are saying about Jesus is indeed consistent with the Jesus of history and not some invention of ourselves. But you are right, accepting the legitimacy of that authority is a different matter. Anyway, there is a lot to unpack here. So if you stick around on Veracity for awhile, I hope we can explore that further.

You have brought up some thoughtful criticisms that speak to the nature of particular truth claims and the relationship between grace and works in salvation. I wrote a series of blog posts that explore these topics in greater detail. I have edited the current blog post and referenced these other Veracity blog postings at the very end. So if you have the time to look into them, I would enjoy getting your feedback.

Blessings to you,

Clarke

LikeLike