Members of a modern Hutterite colony, an Anabaptist group that practices sharing a “community of goods.”

Does the Bible teach that Christians should be communists, or socialists?

One of the hallmarks of the Radical Reformation, in the 16th century, was a desire to return back to following the pattern of the early church, who held “all things in common,” as taught in the Book of Acts. But what does it mean to hold “all things in common,” and does that apply to the church today? Is “communism” taught in the Bible? A look back to the 16th century controversy might give us some perspective in answering these questions.

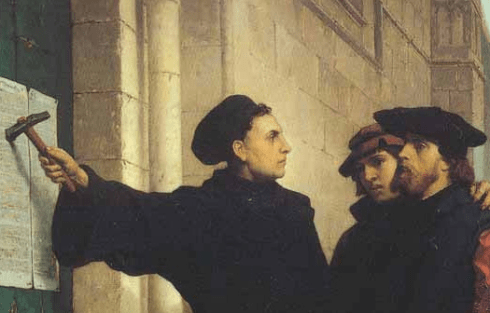

Most Protestant Christians today trace their heritage back to what is called the magisterial Reformation of the 16th century. Early Reformers, such as Ulrich Zwingli of Switzerland, and Martin Luther of Germany, sought to work with the governing authorities, the magistrate, to implement the reforms of their associated movements. Both Zwingli and Luther believed that the medieval church had drifted away from its Scriptural moorings, over the years, and so they wanted to get people back to the Bible. But they wanted to do so in an orderly manner, which required the government’s assistance, as the contemporary values of religious freedom, or what some call “the separation of church and state,” did not exist back then.

However, in Ulrich Zwingli’s Switzerland, some people wanted to go further than where Zwingli was prepared to go. The controversy was partly based on two passages in the Book of Acts, when the message of the Gospel began to spread rapidly after Christ’s Resurrection, in the 1st century A.D.:

- 44 And all who believed were together and had all things in common. 45 And they were selling their possessions and belongings and distributing the proceeds to all, as any had need. 46 And day by day, attending the temple together and breaking bread in their homes, they received their food with glad and generous hearts (Acts 2:44-46 ESV).

- 32 Now the full number of those who believed were of one heart and soul, and no one said that any of the things that belonged to him was his own, but they had everything in common. 33 And with great power the apostles were giving their testimony to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus, and great grace was upon them all. 34 There was not a needy person among them, for as many as were owners of lands or houses sold them and brought the proceeds of what was sold 35 and laid it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to each as any had need. 36 Thus Joseph, who was also called by the apostles Barnabas (which means son of encouragement), a Levite, a native of Cyprus, 37 sold a field that belonged to him and brought the money and laid it at the apostles’ feet (Acts 4:32-37 ESV).

The key phrase here is that they “had everything in common.” Some of Zwingli’s followers in Switzerland took this quite literally, believing that all true followers of Christ should renounce all private property, and simply share together in a “community of goods.” That sounds sort of like a Christian version of “socialism” today… or even, “communism.” Continue reading

Not having grown up in the Roman Catholic tradition, I was always puzzled by the whole idea of mortal versus venial sins. What is all of that about, and where is it in the Bible, (or is it)?

Not having grown up in the Roman Catholic tradition, I was always puzzled by the whole idea of mortal versus venial sins. What is all of that about, and where is it in the Bible, (or is it)?