Let us make Paul weird again. In Matthew Thiessen’s A Jewish Paul, which is actually a rather short book, the author packs quite a punch with a core idea in the thought of the Apostle Paul which is often overlooked: Paul’s “Pneumatic Gene Therapy.”

The first blog post of this book review offers an overview and special insights into A Jewish Paul: The Messiah’s Herald to the Gentiles. However, in this second blog post of a two part book review, we focus on Thiessen’s description of “Pneumatic Gene Therapy.”

The story of the Bible focuses on Israel as God’ chosen people. How much more anti-democractic or anti-egalitarian can you get to have a “chosen people” separated out from the other, gentile peoples of the world? But the Christian message according to Paul is a lot about breaking down that barrier between Jew and Gentile, without fundamentally losing the distinctiveness of what it means to be Jewish.

So, we have a problem. Gentiles are outside of the God’s covenant with Israel, but Israel is simultaneously set apart to be a blessing to all of the nations. How then is the gentile problem solved by Jesus, according to Paul, as read by Matthew Thiessen? This is where Thiessen’s most provocative insight comes into play, and it highlights even more the weirdness of Paul.

Pneumatic Gene Therapy

For Paul, gentile believers need to be connected to Abraham, but how? “Abraham is the father of all who believe, and those who trust in the Messiah are Abraham’s seed (Rom. 4:11, 13; Gal. 3:6, 29)” (Thiessen, p. 102). But if circumcision itself fails to properly unite gentile believers in Jesus to Abraham, what does?

Thiessen maintains that Paul knows the solution, as described primarily in Romans 4 and Galatians 3, but it is a solution that is often misunderstood. Thiessen offers his translation of Galatians 3:29: “If you are [part] of the Messiah [ei hymeis Christou], then you are the seed [sperma] of Abraham” (Thiessen, p. 103). Some translations begin this verse with: “And if you are Christ’s” (ESV) or “if you belong to Christ” (NIV). But it takes some unpacking to figure out what it means to “belong to Christ,” for example. Thiessen explains:

“One does this by being immersed into and being clothed in the Messiah. Paul uses the language of containment—entering into (eis) and becoming wrapped by or clothed in (enduō) the Messiah (Gal. 3:27). Such statements encourage us to think in very spatial categories. The Messiah is a location or a container or a sphere into which gentiles must enter in order to be related to Abraham” (Thiessen, p. 103).

But how does one enter that container or sphere? Through the “spirit,” or what Thiessen transliterates from the Greek, “pneuma,” which gives us English words like “pneumatic” and “pneumonia.” In Galatians 4:6, God has sent the pneuma of his Son into the hearts of believers. But what is this pneuma all about?

This is where Matthew Thiessen suggests that Paul’s actual thinking about the pneuma is counter-intuitive to modern readers of Paul. Today, we often think of “spirit” as something which is immaterial. Not so, according to Thiessen. For when the pneuma enters the heart of a believer, the actual stuff of the Messiah enters the body of that believer, permeating, clothing, and indwelling that person (Thiessen, p. 105). This material aspect of “spirit/pneuma” reflects the ancient science of Paul’s day.

Thiessen explains:

“Understandably, this strikes us as odd. The best analogy that I can come up with is a sponge that one immerses in a pail of water. If held underwater long enough, the porous body of the sponge is filled with water while also being surrounded by it. The water simultaneously enters into the sponge and “enclothes” the sponge. This is close to, if not quite the same thing as, what Paul envisages” (Thiessen, p. 105).

Paul’s view of pneuma is related to the ancient Stoic understanding of krasis, whereby two substances can mix with one another, so that the first substance surrounds the second substance, and the second substance surrounds the first substance. Not everyone bought into the Stoic view of krasis. Plutarch thought it was laughable.

But apparently Paul accepted this ancient scientific concept as genuinely real. The spirit/pneuma is made up of the best material available, extremely fine in nature, which then combines with the “flesh and blood” of the believer, made up of coarse material, subject to corruption and decay. Here is how Thiessen translates Romans 8:9-11, where Paul dives deep into his teaching on the spirit/pneuma:

“But you are not in the flesh; you are in the pneuma, since the pneuma of God dwells in you. Anyone who does not have the pneuma of the Messiah is not part of him. But if the Messiah is in you, though the body is dead because of sin, the pneuma is life because of righteousness. If the pneuma of him who raised Jesus from the dead dwells in you, he who raised the Messiah from the dead will give life to your mortal bodies also through his pneuma that dwells in you” (Thiessen, p. 106)

For comparison purposes, consider how the ESV translation renders this passage:

“You, however, are not in the flesh but in the Spirit, if in fact the Spirit of God dwells in you. Anyone who does not have the Spirit of Christ does not belong to him. But if Christ is in you, although the body is dead because of sin, the Spirit is life because of righteousness. If the Spirit of him who raised Jesus from the dead dwells in you, he who raised Christ Jesus[a] from the dead will also give life to your mortal bodies through his Spirit who dwells in you.”

The classic Greek understanding of matter suggested that there are four elements that make up matter: fire, air, earth, and water. But all four of these elements are subject to corruption and decay. So, Aristotle suggested yet a fifth element, aether, which is completely different in that it was eternal, unchanging, and divine (Thiessen, p. 106). So while Paul does not reach for Aristotle’s aether, a similar idea is in his mind. For that which is of the “flesh” (Greek, sarx) is subject to corruption and decay, whereas the spirit/pneuma is not.

The spirit/pneuma then is what connects the gentile believer in Jesus with Abraham, and Abraham’s seed. To summarize the argument made by Paul:

Gentiles need to become Abraham’s sons and seed to inherit God’s promises. The Messiah is Abraham’s son and seed. Gentiles, through faith, receive the Messiah’s essence, his pneuma. Through faith and pneuma they have been placed into the Messiah. The pneuma of the Messiah also infuses their bodies. They have the Messiah’s essence in them, and they exist in the essence of the Messiah. Gentiles have become Abrahamic sons and seed (Thiessen, p. 110-111).

This very material understanding of spirit/pneuma radically goes against the common immaterial view of spirit/pneuma readers today typically have of Paul’s thought. This makes Paul weird.

It also helps to explain one of the most difficult parts of Paul’s great chapter on the resurrection, 1 Corinthians 15:

(42) So is it with the resurrection of the dead. What is sown is perishable; what is raised is imperishable. (43) It is sown in dishonor; it is raised in glory. It is sown in weakness; it is raised in power. (44) It is sown a natural body; it is raised a spiritual body. If there is a natural body, there is also a spiritual body. (45) Thus it is written, “The first man Adam became a living being”; the last Adam became a life-giving spirit. (46) But it is not the spiritual that is first but the natural, and then the spiritual (1 Corinthians 15:42-46 ESV).

What is this passage really talking about?

A Material Spirit?

Matthew Thiessen’s reading of Paul’s notion of “spirit/pneuma” as material resolves several problems. For it identifies a “spiritual body” as being fully material. Just as Christ experienced a fully bodily resurrection, so will believers experience the same type of resurrection, but with a new, incorruptible body in its place of the decaying, corruptible body. The finer material of the spirit/pneuma will overcome the limitations of the coarse material of the flesh.

We may not be able to fully resolve existing questions about what the future resurrected life would look like: for example, will someone born as an amputee have a new bodily limb that they never had in their earthly life? Yet it does establish that a material spirit/pneuma guarantees that the resurrection will be a material existence, and that this new bodily existence will be without corruption.

Thiessen notes that as early as the second century, some Christians no longer accepted Paul’s understanding of a material spirit/pneuma. A pseudepigraphic text that sought to imitate Paul, known to historians as Third Corinthians, tried to argue for a “resurrection of the flesh,” against what the historical Paul was arguing (Thiessen, p. 117). Third Corinthians was probably written by an overly enthusiastic defender of Paul, some time after the apostle’s death, who was bothered that certain people were not believing Jesus to have been genuinely human, susceptible to frailty and death; that is, having human flesh. But in trying to defend the humanity of Jesus, the pseudo-Pauline author of Third Corinthians never bothered to consider the misleading ramifications of promoting a “resurrection of the flesh.”

This “resurrection of the flesh” in Third Corinthians suggests that bodily resurrection is no more than a kind of resuscitation, whereby our old bodies are simply given life back into them, without any substantial change. But a “resurrection of the flesh” means that the body is still susceptible to death and decay. Thankfully, the early church fathers who helped to affirm the New Testament canon we have today were astute enough to recognize the deceptive origins of Third Corinthians, thus excluding it from our New Testament.

The historical Paul may be weird, but the explanatory power is substantial. This ancient understanding of material spirit/pneuma may give greater insight into Paul’s use of the phrase “in Christ” in his letters. This is commonly associated with the “mysticism” of the apostle Paul, whereby a believer somehow “participates” in Christ. But perhaps being “in Christ” is more closely connected to this understanding of material spirit/pneuma as opposed to an ambiguous “mysticism” of what it meant to participate in Christ, which can be quite difficult to grasp.

Furthermore, a material interpretation of “spirit/pneuma” helps to better explain why Paul insists that the church, the gathered believers in Christ, make up what he calls “the body of Christ.” This “body” language is not simply presented as a metaphor in the New Testament. Rather, it suggests that “the Messiah followers are his flesh-and-blood body on earth” (Thiessen, p.119), a theme that Paul elaborates on in 1 Corinthians 12 and Romans 12:4-8.

Paul even combines the corporate body of the Messiah; that is, his church, with the individual bodies of believers, showing that the gathered believers, the body of the Messiah, and the sacred space where God dwells, just as God dwelt in the tabernacle and the temple in the Old Testament, and therefore, Christians should act accordingly with their individual bodies. Thiessen shows that Paul pulls the individual and corporate sense of “body” together in his translation of 1 Corinthians 6:19-20:

“Or do you all not know that your [plural] body [singular!] is a temple of the holy pneuma within you all, which you all have from God, and that you all are not your own? For you all were bought with a price; therefore glorify God in your [plural] body [singular]” (Thiessen, p. 121).

Modern English translations rarely demonstrate this intentional connection of the plural “your” with the singular “body,” as English lacks a particular second person plural pronoun as differentiated from second person singular (the primary exception is the old trusty King James Version, which still had a second person plural pronoun, from the Elizabethan era). Certain translations, like the NIV, obscures Paul’s point altogether by wrongly translating “body” as “bodies.”

On numerous occasions, Paul refers to those who are “in Christ‘ as “holy ones” (Here is a short list of such references: Rom. 1:7; 8:27; 12:13; 15:25, 26, 31; 16:2, 15; 1 Cor. 1:2; 6:1, 2; 7:14; 14:33; 16:1, 15; 2 Cor. 1:1; 8:4; 9:1, 12; 13:12; Phil. 1:1; 4:22). Unfortunately, most English translations miss the significance of this terminology by translating this phrase as “saints.” The language of “holy ones” harkens back to this same language found in the Old Testament, such as Zechariah 14:5.

So, who are these “holy ones?” In the Old Testament, as well as Second Temple literature like the Wisdom of Solomon and in the Dead Sea Scrolls, the “holy ones” are identified as being members of Yahweh’s divine council (Thiessen, p. 124ff). This suggests that those who are “in the Messiah,” including both Jew and Gentile are to be somehow connected to God’s divine council. This demonstrates that the Eastern Orthodox view of sanctification as “theosis,” whereby believers in Christ are being made, in some sense, to be “divine,” is not just some late theological development unique to Eastern Orthodoxy, but that goes back to very language of the New Testament (see 1 Thessalonians 3:13. The NIV translation is one of the few English translations that gets this verse right!).

It should not be a surprise then that in 1 Corinthians 6:2-3, Paul is teaching that believers in Christ will one day judge angelic, divine beings. This is not to be confused with a Mormon understanding that certain human beings will become “gods” themselves, suggesting that such humans will become just as the God of the Bible is now. Rather, the God of the Bible is supreme overall.

“This does not threaten Paul’s belief in one supreme God; it rather confirms it. The supreme God is God by nature (physis) and has the power to deify others. All other gods are gods only by God’s gift or grace, a gift that is newly available to humanity in and through the Messiah and the Messiah’s pneuma” (Thiessen, p. 128).

Correcting False Views About the Resurrection

Here is my biggest takeaway from A Jewish Paul. Matthew Thiessen’s thesis about a material concept of “spirit” (pneuma), as opposed to a non-material concept, clears away confusion about the doctrine of the resurrection. Look at how the pseudepigraphic author of Third Corinthians (noted above) gets Paul wrong in comparison to what Thiessen says about 1 Corinthians 15, the greatest chapter in the New Testament about the resurrection in the world to come:

If we allow our own astrophysics to creep into our readings of 1 Corinthians 15, then we are bound to run into problems. Since most (perhaps all) of us make a sharp distinction between the material and spiritual realms, we might think that when Paul says “spiritual,” he must mean nonphysical. Consider the NRSVue translation of 1 Corinthians 15:44, which distinguishes between the first body, which is sown, and the second body, which comes out of the sown seed: “It is sown a physical body; it is raised a spiritual body. If there is a physical body, there is also a spiritual body.” There are at least two problems with this translation. First, the Greek word the translators render as “physical” is psychikos, a word that does not mean physical. Instead, it is related to the Greek word for soul—psychē. So while Paul is referring to a material body, that is not the point of the distinction he is making between the two bodies. Rather, he alludes to Genesis 2:7, which speaks of God making the earthling into a living soul (eis psychēn zōsan). In contrast to this original psychikos (soulish) body, the resurrection body will be a pneumatic body. Second, I prefer to use the term pneumatic rather than spiritual because it helps modern readers distance themselves from the assumption that what is spiritual is the opposite of material or physical. (Think, for example, of how often you hear that you must be grateful for your spiritual blessings rather than your material blessings.) (Thiessen, p. 142).

It is remarkable how so many popular English Bible translations get 1 Corinthians 15:44 wrong. The Common English Bible (CEB), the Contemporary English Version (CEV), the older Revised Standard Version (RSV), and even The Message all get this wrong, just as the NRSVue has done. By translating psychikos as “physical,” this implies that the resurrection body is in contrast with the physical, suggesting that the “spiritual body” is not material. Thankfully, there are translations like the NIV, NASB, and ESV that get it right:

It is sown a natural body; it is raised a spiritual body. If there is a natural body, there is also a spiritual body (1 Corinthians 15:44 ESV).

Being sown a “natural body” is the much better translation, and not a “physical body.” (A recent interview with New Testament scholar Michael Licona underscores this point). Sadly, such mistranslations of the Bible have given many Christians the wrong impression that our resurrection bodies will have no material element.

This wrong interpretation suggests that at the resurrection we will simply have some ethereal existence floating on the clouds, kind of like the Hollywood picture of wearing white robes, with halos, and even sprouting wings, with lots of harp playing going on. In other words, “going to heaven when we die” in this wrong view of resurrection is about escaping the human body, with all of its frailties, instead of a transformation of the human body to become perfected. In contrast, a more biblical and accurate perspective has our resurrected bodies in a material form existing within the realm of the “new heaven and new earth” (Revelation 21:1).

If there is but one critical lesson to learn about “pneumatic gene therapy” in the writings of Paul, it would be this one!

Pushback Against the “Pneumatic Gene Therapy”

Perhaps the strongest pushback against Thiessen’s “Pneumatic Gene Therapy” proposal is what is to be done with Paul’s doctrine of the Holy Spirit? In many of the passages where Thiessen cites the “pneuma” as this material conception of “spirit” some translations instead capitalize the word as “Spirit,” thereby suggesting that Paul has in view the third person of the Trinity, the Holy Spirit.

It is important to note that the original Greek of the New Testament does not use capitalization for “spirit/pneuma,” or for anything else. The King James Version translation set a type of precedent of capitalizing “Spirit,” an interpretive decision which has been a difficult habit to shake for subsequent English translations. The KJV often distinguishes between some other “spirit” and the “Holy Spirit” by simply capitalizing the single word, “Spirit,” as in Romans 8:15:

For ye have not received the spirit of bondage again to fear; but ye have received the Spirit of adoption, whereby we cry, Abba, Father.

This might indeed be the right way to interpret this verse, but capitalization of the latter is not found in the original Greek. Context is key when trying to figure out the correct interpretation for any passage of Scripture, and it is not entirely self-evident as to why the KJV translators capitalized “Spirit” sometimes but not other times. Perhaps the “spirit of adoption” is meant by Paul to mean the finest material available, associated with being a new creature in Christ, versus the inferior “spirit of bondage,” which suggests the coarser, corruptible material of the fallen world. It may not necessarily suggest that the “spirit of adoption” here is the third person of the Trinity, in Paul’s mind.

Clinging to a more non-material “spirit of adoption” might well explain the rise of the idea that believers “go to the heaven” when they die, and stay there, living up on some puffy clouds, bearing ethereal wings, or something else which owes itself more towards the Gnostic idea of getting rid of our bodily existence in the afterlife. This Gnosticism is very much at odds with historic orthodox Christianity, which insists that believers will dwell bodily, exploring all that the “new heaven and new earth” has to offer. Perhaps we should be much slower to think “Holy Spirit” when we read of the “pneuma/spirit,” at least in certain passages of our New Testament.

Yet a purely material conceptualization of the “Holy Spirit” does seem at odds with historic Christian orthodoxy. I am not saying Thiessen’s “Pneumatic Gene Therapy” idea is misleading or incorrect. I am just wondering how this all fits in with Paul’s understanding of the Holy Spirit.

But there could be an answer to this objection. It is quite possible that not all Pauline references to the “pneuma” have the ancient material sense of “spirit” in mind. There are potentially other Pauline uses of “pneuma” that have the Holy Spirit in view, as opposed to a material infusion of “spirit/pneuma,” congruent with Stoic philosophy.

For example, Romans 5:5 specifically mentions the “Holy Spirit,” as in “God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit who has been given to us” (ESV). The ESV here suggests a personal and less material sense of “spirit/pneuma.” But in the same letter, particularly in chapter 8, Paul speaks of the “spirit/pneuma” in more of the material sense numerous times, as in: “For to set the mind on the flesh is death, but to set the mind on the [spirit] is life and peace” (Romans 8:6 ESV, without capitalizing). Compare this with the KJV which intentionally does not capitalize the “spirit,” translating the phrasing differently: “For to be carnally minded is death; but to be [spiritually] minded is life and peace.”

Yet then Paul might be shifting back and forth between the “Holy Spirit” or “Spirit of God“, and the “spirit/pneuma” in the material sense, later in Romans 8:13-14: “For if you live according to the flesh you will die, but if by the [Spirit/spirit] you put to death the deeds of the body, you will live. For all who are led by the [Spirit/spirit] of God are sons of God” (ESV). Is the first reference to pneuma in the material sense, and the second reference in the sense of the Holy Spirit? The ESV translation by default capitalizes “S/spirit,” which suggests that both references are to the “Holy Spirit,” but perhaps this is not the best way to understand Paul. Unfortunately, Matthew Thiessen does not address this particular issue as to how the Holy Spirit and “spirit/pneuma” in the material sense relate to one another.

What I would like to see is other critics taking a good look at Thiessen’s thesis, and suggest if a convincing explanation could be found to figure out why this Pauline concept of a material “spirit/pneuma” was relatively so quickly lost during the era of the early church, at least among some Christians. Is it possible for a robust Pauline theology of the Holy Spirit to be synthesized with Matthew Thiessen’s thesis? To my knowledge, there was no early church effort among the historically orthodox to strongly deny such a “pneumatic gene therapy,” though I could be proven wrong here. As I understand Thiessen’s thesis, it could simply have been that a material concept of “spirit/pneuma” was simply forgotten over time, at least in popular thought, as opposed to being actively rejected by certain groups of Christians, whereby debates concerning the “Spirit” in Paul’s writings eventually got taken over by other theological concerns.

A second pushback could be made by those who bristle at the thought that Paul might have embraced an ancient, obsolete scientific view of matter to explain one of the central themes in Pauline theology taught within his New Testament letters. Would God really accommodate to the apostle’s fallible, yet broadly accepted view of “spirit/pneuma” in Paul’s day in order to reveal divine, infallible truth?

For those who say that such a suggestion of divine accommodation violates their sense of the inspiration of Scripture, pneumatic gene therapy will find a difficult path towards acceptance. But those who struggle with such a prospect, they already have enough on their hands trying to explain why the human heart, which according to modern science, is but a sophisticated pump, is nevertheless described in the Bible as the seat of human emotions (1 Samuel 13:14, Psalm 73:21). They also struggle with the notion of the kidneys being a similar source for human emotions (Proverbs 23:16), when modern science tells us that the kidneys have a different function, that of being a filter to rid the body of substances that threaten it. Do we need to say anything more about the supposed “teaching” of Genesis 1 that we will live on a flat earth? I have written before on Veracity that it would be unfair to judge the Bible negatively simply because the scientific views held during ancient times had not yet caught up with contemporary understandings of biology and cosmology.

These possible pushbacks aside, Thiessen’s material interpretation of “pneuma” makes for the most thought-provoking contribution to our understanding of Paul to be found in A Jewish Paul. The explanatory power of Thiessen’s thesis is indeed very compelling. While there are still some lingering questions in my mind, I am pretty much on-board with Thiessen’s thesis.

A Recommendation for Reading A Jewish Paul

Far too often in some conservative evangelical circles, various reassessments of Pauline theology have resulted in a false dichotomy whereby a “new perspective” is thought to cancel out an “old perspective” regarding Paul (Read here for an introduction to the so-called “New Perspective on Paul”). I have friends of mine who are immediately suspicious of anything “new” regarding a “New Perspective Paul,” as this suggests that something “new” must be something “liberal,” and therefore not based on the Bible. But “new” in this context should be better understood as recovering something that has been lost and forgotten due to layers and layers of tradition.

However, such suspicion is not totally unwarranted, as some proponents of such “new perspectives” have too excitedly tried to show that everything you once thought about Paul has now been “proven” to be wrong. Why? Because some scholar with a PhD said so.

Thankfully, Matthew Thiessen does not do that in this book. Thiessen is sympathetic to such concerns. A renewed focus on Paul’s Second Temple Jewish context need not cancel out a robust and classical doctrine of justification by faith. If anything, a fresh look at Paul can help to better sharpen our theological understanding of Paul, rather than blunt it.

Perhaps the best example to be considered is the status of Luther’s view of the righteousness of Christ being imputed to the Christian believer, a doctrine that a number of proponents of the New Perspective on Paul deny. Those who oppose the New Perspective on Paul often do so because they believe that such advances in our understanding of Paul today have obscured this doctrine, to the detriment of the Gospel. But Matthew Thiessen’s proposal helps to give us a different way of thinking through this controversy. For if it is a kind of pneumatic gene therapy that makes one belong to the people of God, and find salvation, then this surely is not something which originates from one’s self. This pretty much rules out any kind of “works-righteousness” approach to salvation, which is consistent with Martin Luther’s 16th century concern, while reframing our thought to be more consistent with Paul’s original 1st century perspective.

According to the old Greek way of looking at matter, based on the four primary elements of earth, sky, fire, and water, human existence by default dwells within this state of coarse matter. To move towards a state of the finest matter, that of the “spirit/pneuma,” Paul in no way would suggest that can be accomplished by human effort alone. Rather, in order to attain this finest matter, it must be given to us, a reality that rules out any idea of a “works-based” righteousness. In this sense, to say that Christ’s righteousness is “imputed” to us, as Protestant Reformers like Martin Luther insisted, is not that far off from saying that the Messiah gives us spirit/pneuma to transform us. It would be of great interest if Thiessen would explore this theme in some follow-up book.

Paul’s theology is indeed rich, teaching that salvation by good works is not achievable by human effort, while simultaneously affirming the Jewishness of Paul. Matthew Thiessen backs up his argument not by any appeal to some new idea, but by recovering the ancient sources to make his case. Whether or not Thiessen has solidly interpreted those ancient sources is up for the reader to assess. No matter where the reader lands, Matthew Thiessen gives the reader a lot to think about.

If I could recommend a single book that acts like a one-stop shop that gives an overview of where Pauline studies is today, without a lot of academic jargon, it would be Matthew Thiessen’s A Jewish Paul. Paula Fredriksens’ impressively engaging Paul: The Pagans’ Apostle covers a lot of the same ground as Thiessen’s A Jewish Paul, and comes to broadly overlapping conclusions, as I have reviewed here before two years ago on Veracity. Paula Fredriksen is a more senior, experienced scholar than Matthew Thiessen. But Fredriksen’s still extraordinary book is more difficult to penetrate for the general reader, whereas Thiessen’s book is easier to grasp and brief in comparison. For the best book review of Matthew Thiessen’s A Jewish Paul, read what Brad East had to say, which gave me plenty of food for thought in this review.

And a Cautionary Note For Reading A Jewish Paul

I could continue with the accolades for A Jewish Paul. Matthew Thiessen is a fine scholar and enjoyable to read. Nevertheless, there are still some problematic issues with Matthew Thiessen’s work that might give at least some readers pause. I could be very wrong on this, but I am doubtful that Thiessen would consider himself an “evangelical” Christian scholar, as he rejects (or to be more generous, at least downplays) a number of historically orthodox views of the Christian faith. He embraces a number of ideas popular today among many critical scholars that might bother some in his audience. This is disappointing, but not altogether unexpected.

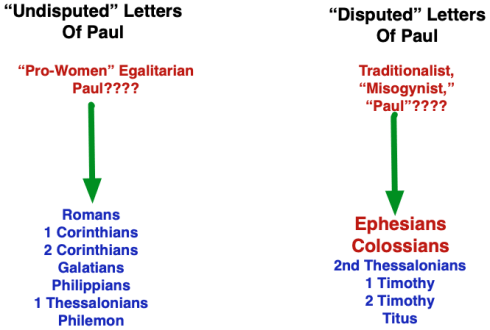

Three examples stand out. First, Thiessen follows the common critical view that Paul did not write all thirteen letters in the New Testament, associated with his name. He is largely convinced that Paul did not write the pastoral letters (1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, Titus), and he is unsure about 2 Thessalonians, Ephesians, and Colossians. Nevertheless, he (cautiously) uses evidence found in all thirteen letters associated with Paul to make his case (Thiessen, p. 51), which suggests that he might be open to being wrong about the disputed status of certain letters from Paul.

Good for him. I will just say that I am persuaded that all thirteen letters in our New Testament all derive from Paul’s authority, though he probably enlisted significant help from competent secretaries he trusted, particularly in the case of 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy and Titus, the most disputed of the Pauline writings.

Furthermore, Thiessen remarks and asks, “Paul was not a trinitarian, but do his writings perhaps inevitably point in trinitarian directions?” (Thiessen, p. 113). I wonder if Thiessen could have reframed this a little differently. Some readers will be annoyed to think that Paul was not trinitarian from the start, at least implicitly, but Thiessen is nevertheless open to thinking that Paul’s ideas do lend themselves towards a fully trinitarian theology articulated at the councils of Nicea and Constantinople in the 4th century. Still, Thiessen’s stark remark about Paul not being a trinitarian is a curious posture to take.

Here is how I would put it: While Paul was not explicitly trinitarian, Paul was implicitly trinitarian, as those early church fathers eventually understood the doctrine of the trinity by the end of the 4th century.

On top of that, it was not clear to me as to what Matthew Thiessen thinks about the exclusive claims of Christ. On the one hand, Thiessen emphasizes that Paul unequivocally taught that one must believe in Jesus as the Messiah. There is no denying Paul’s exclusivity about Jesus. Then Thiessen gives the analogy of being on the Titanic when it starts to sink. The exclusive truth claim of historic orthodox Christianity is akin to the cry that one must board one of the lifeboats, or else one may die. The lifeboat on the Titanic represents Jesus as the only way to salvation. “Many Christians believe that they have a moral obligation to tell people throughout the world that they are doomed and that they need the lifeboat” (Thiessen, p. 43). This has been the historically orthodox position, despite various attempts to posit a doctrine like universalism. Thiessen on the other hand refrains from telling the reader his own position.

One particular critique of the “Paul Within Judaism” school of thought is that it might be making the exclusive truth-claims of Christianity not-so exclusive. Thiessen is hesitant about applying the “Paul Within Judaism” label to himself, but it left me as a reader scratching my head. This theological issue is probably best understood as one of those mysteries of the faith: where we must simultaneously uphold the uniqueness and supremacy of Christ, while trusting in the goodness and wisdom of God in dealing with those like the Jewish people, and others, who do not outwardly make a profession of Christian faith. Unfortunately, Thiessen left me hanging on this one. Again, this is disappointing.

Salvation is salvation in Christ, and Christ alone. But from our finite human perspective we can nevertheless trust in God’s sovereign purposes and the wideness of God’s mercy to save in ways that we can not fully understand.

A Jewish Paul: A Final Assessment

However, while none of these comments above from A Jewish Paul are ringing endorsements of classic, historically orthodox Christian claims, this should not discourage potential readers from taking in what Matthew Thiessen has to say. A Jewish Paul wants to engage with all Christian believers across the theological spectrum to help us to gain a more accurate and nuanced appreciation for Paul and his message.

A Jewish Paul also serves as a catalyst for trying to purge centuries of antisemitic tropes Christians have at times unwittingly wielded against Jews. While I still consider the great Reformer, Martin Luther, one of my favorite Protestant heroes, Luther went off the rails towards the end of life writing some of the worst, anti-Jewish writings imaginable. Luther’s failure to see the real Jewish-ness of Paul is a fault that we as Protestant evangelicals need to get past and overcome. I am grateful that Matthew Thiessen is helping to try to set the record straight.

As a conservative evangelical myself, I think Matthew Thiessen’s A Jewish Paul is a wonderful book, which has taught me a lot, even though I find myself wondering about or disagreeing with the author on certain fundamental convictions. I can still learn from someone who does not share the exact same evangelical commitments that I have. As a book of less than 200 pages, A Jewish Paul is a perfect introduction into the state of contemporary scholarship regarding the apostle Paul, written at an accessible level. I plan on referring to A Jewish Paul often when I read Paul. A Jewish Paul is an invaluable contribution to the discussion, deserving the widest readership possible, for both scholars and laypersons alike.