What should be our motivation for giving to the work of Christian ministry? Building on the previous post in this series, we can take a good look at this question.

God’s generosity towards us should be our motivation for our giving generously towards God’s work in the world. Yet some Christians argue that believers should give a tenth of one’s income to the local church, and anything above and beyond that optionally to any form of Christian work. Such faithful Christians are well-intended in this way of thinking, yet the previous blog post in this series suggests that the biblical interpretation behind this mindset is problematic. There is a better way to think about giving.

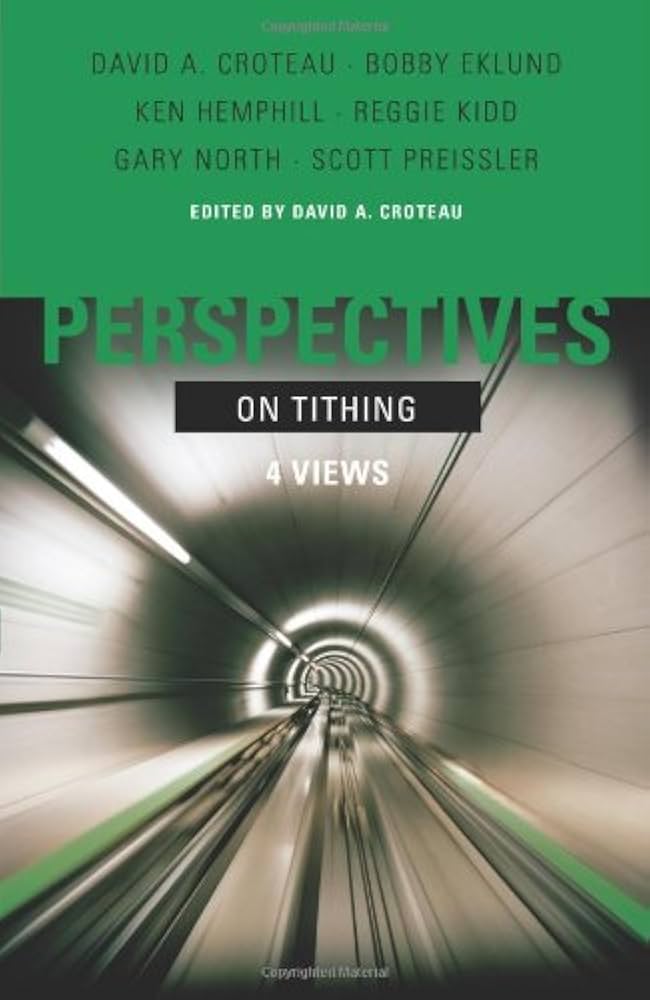

However, before one can neatly, or perhaps too neatly, conclude that the Old Covenant tithe is no longer required under the New Covenant, it is important to address a strong counterargument. As I was reading Perspectives on Tithing: 4 Views, I learned that a number of advocates for a New Covenant tithe argue that the concept of the tithe precedes the actual Old Covenant instantiated under Moses. Because the tithe comes prior to the giving of the Law, it is argued that any reading of the New Testament can not invalidate any commands of God given prior to the giving of the Law to Moses in the wilderness.

Once this thoughtful counterargument is addressed, certain principles can be drawn from the Old Testament tithe, that can help us to see the pattern of New Testament, generous, grace-motivated giving.

Does the practice of tithing belong to the Old Covenant, or is it relevant to the New Covenant as well? If so, what does “tithing” mean for Christians today?

A Weakness in the “Post-Tithing” View

One particular weakness of a “post-tithing” view, which suggests that an exact tenth of one’s income is neither necessarily nor absolutely required to be given to the local church, is that there is no explicit New Testament reference which says that tithing no longer applies to the New Testament Christian, one under the New Covenant. Advocates of tithing today do have a point here. Paul explicitly teaches that Gentile followers of Christ are no longer required to undergo physical circumcision (Galatians 5:1-6). But there is no specific statement in the New Testament corresponding to tithing like this.

Therefore, if someone holds the view that every law mentioned in the Old Testament is applicable to Christians today living under the New Covenant, unless there is some explicit statement saying that something is negated or otherwise abrogated in the pages of the New Testament, then this would be a good argument against any kind of “post-tithing” view (A “post-tithing” view relegates the tithe to belonging only to the Old Covenant).

However, there are plenty of commands given in the Levitical law which Christians today do not necessarily follow, with no explicit mention about them in the New Testament. Christians in the banking or home mortgage industry continue to offer loans to people, by charging interest, despite the command in Leviticus 25:36-37, which says the Israelites were forbidden to charge their fellow Israelite any interest under any circumstance. I am probably wearing some piece of clothing today, made up of a mixture of cotton and some synthetic fabric, despite the fact that Leviticus 19:19 forbade the ancient Israelite, aside from the Levitical priests, from wearing mixtures of any kind.

The New Testament says nothing about the ethics of charging interest on loans, nor about what types of fabric a Christian should wear.

The reason why advocates of a “post-tithing” approach to giving make their case is because tithing, along with not charging any interest in loans, or wearing two different kinds of fabric, are all regulations established in the first five books of the Bible, which are closely associated with the ancient Israelite worship of Yahweh at the tabernacle/temple. Because Jesus Christ has fulfilled the Law of Moses, these temple-specific practices are no longer required by the New Testament believer. However, what if it could be demonstrated that tithing was an established practice, commanded by God, prior to the giving of the Law to Moses?1

In what sense does the Old Testament teaching on tithing teach us as Christians living under the New Covenant how to practice our faith today?

The Melchizedek Factor and Tithing

The primary proof text for the argument of a “pre-Law” prescription for the tithe involves the figure of Melchizedek, as taught in Genesis and reinforced in the New Testament Book of Hebrews. In Genesis 14, Abraham’s nephew, Lot, had been taken captive, and so Abraham engaged in a successful military mission to save Lot. The Melchizedek passage in Genesis is fairly brief, where Melchizedek meets Abraham (who was still called Abram at that point in time) after the latter’s victory:2

And Melchizedek king of Salem brought out bread and wine. (He was priest of God Most High.) And he blessed him and said,

“Blessed be Abram by God Most High,

Possessor of heaven and earth;

and blessed be God Most High,

who has delivered your enemies into your hand!”

And Abram gave him a tenth of everything (Genesis 14:18-20 ESV).

For such a brief passage, Jewish writers in the period of Second Temple Judaism made a big deal about Melchizedek, an idea reinforced in the Book of Hebrews. For example, the Dead Sea Scrolls mention Melchizedek frequently. One thing that is so curious about this passage is the concise reference to a tithe, or “tenth”: “Abram gave him a tenth of everything.”3

What motivated Abraham to give a tithe to Melchizedek? Unfortunately, the text never tells us. There is nothing in the text which says that God commanded Abraham to give this tithe. It is quite probable that Abraham’s tithe was given voluntarily. If it was voluntary, then it is quite unlike the tithes taught in Leviticus, which are mandatory and not voluntary.4

Also, the text only tells us of this one time Abraham gave a tithe. Nothing tells us that the tithe was repeated. Again, this is quite unlike the tithe requirements found in Leviticus.5

Melchizedek in the Book of Hebrews: What Was the Intent of Author?

Nevertheless, the example of Abraham’s tithe to Melchizedek is often pivotal for those who propose an on-going relevance for the tithe for New Covenant believers. Hebrews 7:1-10 acts as New Testament commentary on the incident with Abraham and Melchizedek:

(1) For this Melchizedek, king of Salem, priest of the Most High God, met Abraham returning from the slaughter of the kings and blessed him, (2) and to him Abraham apportioned a tenth part of everything. He is first, by translation of his name, king of righteousness, and then he is also king of Salem, that is, king of peace. (3) He is without father or mother or genealogy, having neither beginning of days nor end of life, but resembling the Son of God he continues a priest forever.

(4) See how great this man was to whom Abraham the patriarch gave a tenth of the spoils! (5) And those descendants of Levi who receive the priestly office have a commandment in the law to take tithes from the people, that is, from their brothers, though these also are descended from Abraham. (6) But this man who does not have his descent from them received tithes from Abraham and blessed him who had the promises. (7) It is beyond dispute that the inferior is blessed by the superior. (8) In the one case tithes are received by mortal men, but in the other case, by one of whom it is testified that he lives. (9) One might even say that Levi himself, who receives tithes, paid tithes through Abraham, (10) for he was still in the loins of his ancestor when Melchizedek met him.

The context for Hebrews 7:1-10 is crucial for understanding what is going on in this passage. Hebrews 7:1-10 belongs to an extended discourse arguing that Jesus is a high priest in the order of Melchizedek, from Hebrews 5-10. The main argument throughout the book is that Jesus is better than the angels, better than Moses, and better than the Levitical priestly system. The author of the text is trying to tell his readers to remember that Jesus is greater, and so his readers should not go back to their old ways. In Hebrews 7:1-10, we are told about the greatness of Melchizedek, and that the priesthood of Melchizedek is greater than the Levitical priesthood. Later in Hebrews 7:11-22, the text specifically associates Jesus as being the one who stands in the priestly order of Melchizedek.6

The point of Abraham paying a tithe to Melchizedek is to acknowledge that Melchizedek was greater than Abraham, and that the greater one blessed the lesser one. Since the Levites descend from Abraham, Melchizedek’s priesthood is shown to be greater than the Levitcal priesthood. Therefore, since Jesus is a priest within the order of Melchizedek, the priesthood of Jesus is greater than the Levitical priesthood. To make sure that the reader gets the message, the author summarizes the lesson to be learned:

“Now the point in what we are saying is this: we have such a high priest, one who is seated at the right hand of the throne of the Majesty in heaven, a minister in the holy places, in the true tent that the Lord set up, not man” (Hebrews 8:1-2 ESV)

Pro-tithing advocates will then appeal to Hebrews 7 to say that just as Abraham paid a tithe to Melchizedek that Christians today are to pay tithes to Jesus, via the local church. In Perspectives on Tithing: 4 Views, Hemphill and Eklund conclude this part of their argument by saying: “If Abram tithed to Melchizedek, would it not follow that the Christian would offer tithes to the great high priest who is greater than Melchizedek?“7

However, this conclusion merely assumes that this teaching on tithing is part of the intent of the author. While this might be a secondary purpose of the author, such a purpose is not made explicit in the text. Instead, Abraham’s tithe is mentioned as an illustration of the main point that the author of Hebrews is trying to make.

Furthermore, even if this is a fully warranted conclusion, it is difficult to interpret what kind of tithe the Christian is expected to give. In Abraham’s case, Hebrews 7 explicitly tells us in verse 7 that the tithe came from the spoils of war. Does this mean that the only situation that applies here is that the Christian should tithe when they have succeeded in a military battle, and obtained booty which could be tithed to the local church? If so, this would be a most odd application of tithing from the New Testament.8

The Levites Tithing Through the “Loins of Their Ancestor?”

If Abraham’s tithing on war booty is not in view, then how does one arrive at the standard pro-tithing conclusion from this passage? On what basis should this Abrahamic tithe be connected to giving a tenth of one’s income to the local church? Why should it not also include all of the tithes that were required of the Israelites, which totals up to around 23%, including the Festival and Charity tithes, and not just the Levitical tithes given to the priests?

Moreover, verse 9 suggests that Abraham was a proxy by which the Levites were able to pay their “tithes” to Melchizedek. Levi, the father of the Levites, was represented by Abraham before Melchizedek, through the “loins of their ancestor” (ESV). The NIV translates the next verse (verse 10), “because when Melchizedek met Abraham, Levi was still in the body of his ancestor.”

The author intends this as an illustration to demonstrate that the priesthood of Melchizedek is superior to the priesthood of the Levites. At best, one could say that Abraham is still a proxy tithe payer to Melchizedek on behalf of Christians today, who form the royal priesthood of the New Covenant. But it does not necessarily follow that because of this, Christians today should pay tithes. At best, assuming that we are supposed to tithe to Jesus, that can only possibly make sense if somehow Jesus was and still is Melchizedek, instead of specifically being a priest in the order of Melchizedek, as the text argues. True, Melchizedek is described as one who is not mortal, an analogy to Jesus’ resurrected existence. But identifying Jesus as Melchizedek himself is a speculative argument which goes beyond the evidence within the text, an argument which is at best tangential to the purpose of the author of Hebrews.9

Given all of these problems, it is difficult to conclude that the Abraham/Melchizedek tithing example from Genesis and Hebrews establishes the principle of tithing as an ongoing imperative for today’s Christian, on the basis of it being a commandment which precedes the giving of the Law of Moses to the Israelites, and therefore not subject to being superseded.10

Perspectives on Tithing: Four Views, edited by David A. Croteau, features four essays by Ken Hemphill & Bobby Eklund, David Croteau, Reggie Kidd, and Gary North, covering different views on tithing and interacting with many of the most relevant texts in Scripture.

The New Testament Motivation for Giving

After reading all this so far, it might appear to some that there is no use for tithing at all, in all the muddle of these various interpretations. However, this is simply not true. While the pro-tithing argument does have many problems with it, there are some fundamental ideas associated with tithing that are vitally important for a Christian today. Those living under the New Covenant, can apply the principle behind tithing today, without getting caught up in troublesome controversies about tithing percentages, what constitutes “income,” tithing on gross pay versus net pay, who should receive such tithes, whatever they are, etc.

First, it is important to acknowledge that everything belongs to God, anyway… and that means 100%, not just 10% of one’s income. “Behold, to the Lord your God belong heaven and the heaven of heavens, the earth with all that is in it” (Deuteronomy 10:14). Everything we have is a gift from God. “Every good gift and every perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of lights, with whom there is no variation or shadow due to change” (James 1:17).

Furthermore, we are called to be good stewards of all that God has given us, just as Adam was told to tend and care for the garden (Genesis 2:15). Anything we claim for ourselves actually comes to us from God, even our finances (Deut. 8:17-18). Jesus himself instructs his followers to handle worldly wealth well (Luke 16:11). Whatever gifts we have received, we have been instructed to share it well with others (1 Peter 4:1-10). The more we realize how generous God has been towards us, the more we will be able to be generous towards others. Jesus himself said that is more blessed to give than to receive (Acts 20:35).

The Apostle Paul gives us the most instruction in the New Testament about generous giving, and in supporting the work of the local church, and assisting others in the church. When it comes to supporting Christian workers, Paul tells us that workers deserve their keep (1 Timothy 5:18). He also states this in 1 Corinthians 9:13-14:11

Do you not know that those who are employed in the temple service get their food from the temple, and those who serve at the altar share in the sacrificial offerings? In the same way, the Lord commanded that those who proclaim the gospel should get their living by the gospel.

We are therefore commanded to support Christian workers, but how should we go about doing that? Paul gives us a concrete situation, whereby he was raising money to give to the church in Jerusalem, from churches in Gentile areas. One principle here is to set aside funds on a regular basis:12

“Now concerning the collection for the saints: as I directed the churches of Galatia, so you also are to do. On the first day of every week, each of you is to put something aside and store it up, as he may prosper, so that there will be no collecting when I come. And when I arrive, I will send those whom you accredit by letter to carry your gift to Jerusalem” (I Corinthians 16:1-3).

The heart of Paul’s model of generous, grace-motivated giving, starting with the right motivations, is found in 2 Corinthians 8-9. These two chapters are worthy of extended meditation, but there are some notable points to highlight: From 2 Corinthians 8:1: “…[from] their abundance of joy and their extreme poverty have overflowed in a wealth of generosity on their part.”

From 2 Corinthians 8:8-9: “ I say this not as a command, but to prove by the earnestness of others that your love also is genuine. For you know the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, that though he was rich, yet for your sake he became poor, so that you by his poverty might become rich.”

What stands out as central in Paul’s thinking comes from 2 Corinthians 9:6-8:

“The point is this: whoever sows sparingly will also reap sparingly, and whoever sows bountifully will also reap bountifully. Each one must give as he has decided in his heart, not reluctantly or under compulsion, for God loves a cheerful giver. And God is able to make all grace abound to you, so that having all sufficiency in all things at all times, you may abound in every good work.”

God loves a cheerful giver, who gives neither reluctantly nor out of compulsion. This is furthermore why taking the Old Covenant teaching on tithing and somehow flatly importing that into the New Covenant does not match. For under the Old Covenant, the various tithes mentioned in the previous blog post in this series were obligations to serve the practices of the tabernacle/temple. Paul, on the other hand, wants Christians to be motivated to give out of a spirit of generosity, not a spirit of compulsion. Christians can still “tithe” in some sense, but it should be transformed by the New Testament understanding that we are to give generously because God in Christ has given so generously to us.

Yes, we are commanded to give, but the exact percentage, exacting to whom we give, etc., is not something where we can simply check off a box of some 10%, and safely conclude that we have done our part. As one of my former Bible teachers, Dick Woodward, used to say, the best way you can examine the integrity of someone’s walk with Jesus is to look at their datebook and their checkbook. How a person spends their time and their money says a lot about the heart of that person and what they really value.

Nevertheless, there is still a place where tithing can help us very practically. For example, if someone does not know how much to give, then giving a tenth of one’s income (a “tithe”) is a good place to start. One thing that is so useful about the Old Testament’s teaching on tithing is that it establishes a general benchmark for our giving as Christians today. But if some are able to give more than 10%, then why not give more?! There are many generous Christians, grateful for what God has given them, who give upwards of 20 to 30 to 40 percent, if not more of their income! Many Christians have the means to give way more than 10%, so insisting on a “tithe” of 10% and no more, misses the whole point about generous, sacrificial, grace-motivated giving.

In saying that, it must be understood that for someone who is just starting out with sacrificial, generous, grace-motivated giving may not be able to give 10%. If giving 10% is not practical at the present time, what about starting with 1%, and then working one’s way upwards in terms of percentage over time?

When it came to the offerings in Leviticus, the law made provision for those who were unable to make a standard offering, due to poverty or other financial constraints. In Leviticus 5:7, if someone was unable to afford a lamb for an offering, that person could bring two turtledoves or two pigeons instead. A principle to be gained from this is to realize that not everyone is able to give 10% of one’s income to the church, at least at the present time, whereas they might be able to give more in the future.

Some people are burdened by financial debts, such as large credit card imbalances. While someone can start giving to God’s work in small amounts, it is better to try to get out of debt first, so that one can give more in the future. What you do not want to do is take out some kind of loan in order to try to meet some supposed tithing obligation. There are plenty of horror stories out there whereby Christians have put themselves into further debt by trying to meet some supposed tithing obligation, only putting their already fragile financial situation in greater jeopardy, or greater debt. Instead, it is better to give out of the abundance of what one has instead of what one does not have. Yes, we are to give sacrificially, but we should also give wisely and with thoughtfulness.13

A Summary on the Bible’s Teaching on Tithing Practice Today

The Old Testament requirement in the Law Moses to tithe to the Temple belongs to the Old Covenant, and not to the New. Instead, the teaching of the New Testament illustrates the principle of sacrificial and generous giving to promote the spread of the Gospel, whether that be through the local church as well as through other ministries across the global church. Just as Christ freely gave to us, we are to freely give as an act of worship to support the work of building God’s Kingdom, through our time, talents, and finances, but not under any compulsion to do so. Giving ten percent is a good baseline, a basic guide for giving, but it is not a legal requirement.

Furthermore, we need to re-evaluate the common teaching that one should be required to “tithe,” or give 10% to the local church, and that anything over that 10% should be considered an optional “offering,” which can be given to any Christian work you wish to support, whether that be your local church, friends who are missionaries, a parachurch ministry, etc. While proponents of such a view mean well, the evidence suggests that such a teaching is nothing more than a tradition, which has been carried down through the years, without much of a careful reading of Scripture.

Nevertheless, it is a tradition that has a good intent behind it. The work of the local church does take precedence. It only makes sense that a Christian should aim to give the lionshare of their regular giving to their local church, of which they are a member, or otherwise involved with on a regular basis, making an investment in that ministry. Giving to missionaries who are friends, parachurch ministries, and other charities probably should come after that. Encouraging believers to give 10% of their income (if not more!) is a good thing, as 100% of what we have belongs to God anyway!

Unfortunately, advocates of tithing can get nervous when they hear New Covenant non-tithing interpreters advance their position, as though a non-tithing position suggests that people should not sacrificially give financially to God’s work. While some might misleadingly lend support to that way of thinking, a responsible New Covenant, non-tithing interpreter of Scripture acknowledges the importance of giving as crucial to the task of accomplishing God’s mission to make disciples of all of the nations. In other words, to say that tithing is no longer a requirement for a believer under the New Covenant does not mean that there is nothing we can learn from the Old Testament about the principle which undergirds the practice of tithing under the Old Covenant.

In my experience, there is a tragic irony here. An emphasis on tithing, that really emphasizes a percentage one “must” give, can actually have the opposite of the desired effect. For if tithing is encouraged in a way that sounds compulsive, many people are actually inclined to give less than if they were presented with a more generous, grace-motivated reason for giving. For if compulsion is felt, the human tendency is either to become resentful or to become burdened with unnecessary guilt, if one can not meet such an obligation.

Instead, when Christians are shown a model of what generosity really looks like, it will encourage them to give more generously. So, it should be no mystery to realize that those Christians who do give at least 10% of their income to God’s work in the world in many cases will actually give much more than 10% of their income, because they greatly enjoy participating in building God’s Kingdom.

It would be foolish to say that the New Covenant abrogation of the Leviticus 25:36-37 restriction against usury, the charging of interest, means that it is somehow okay for a New Covenant believer to rip people off, charging excessive interest in making loans, or otherwise mistreat poor people. Neither is it that the abrogation of the ritual purity requirement to avoid wearing two different kinds of fabric in Leviticus 19:19 mean that it is somehow okay to be disrespectful in how we go about worshipping God. Likewise, to say that a strict form of tithing is part of the Old Covenant and not the New is not some excuse to be stingy. Rather, we can see how the tithe encourages us to be generous in giving, in view of all that Christ has done for us. All of the regulations found in Leviticus have principles behind them that provide instruction for the New Testament Christian, including tithing.14

One final point bears some consideration: Under the Old Covenant, only the Israelites were expected to tithe to support the work of the Temple. The Gentiles were never under that requirement. But under the New Covenant, the Jews could still support the work of the Temple, while the Temple was still standing until 70 C.E., but the Gentiles who came to know the Messiah were no longer required to become Jewish and undergo the Jerusalem Temple-specific act of tithing. Instead, the New Testament teaches that Christians, Jew and Gentile, are to give and give generously, just as God has given so generously to us.

Such a “post-tithing” position was held by certain early church fathers, such as Epiphanius (315-403), who argued that tithes are like circumcision. Just as circumcision is not required for the Gentile Christian, neither is tithing required either. However, it should be noted that there is no one, single consensus view held by the early church fathers regarding tithing. Some like Epiphanius opposed tithing, whereas other church fathers approved of tithing for all Christians. Since there is a wide variety of perspectives regarding tithing held among those in the early church, an examination of church history is of limited value in determining the correct interpretation of Scripture on this question. Arguments based on the exegesis of Scripture alone should take precedence when considering a Christian view of tithing.15

In reviewing Perspectives of Tithing: 4 Views, the arguments from Scripture presented primarily by David Croteau advancing a “post-tithing” view, and secondarily by Reggie Kidd are the most convincing and compelling. While there are some helpful insights brought to bear by Ken Hemphill and Bobby Eklund, and Gary North, in their respective essays, their conclusions come up short in my estimation. The views advanced by Hemphill, Eklund, and North in favor of tithing for today’s Christian present the reader with the most number of problems to be solved, with the fewest solutions offered, whereas Croteau’s proposal, and to some extent, Kidd’s position as well, has the greatest explanatory power. Nevertheless, the very existence of this book indicates that good Christians can and do come to different conclusions regarding the on-going relevance and application of tithing.16

There are surely some who will read this critique of the book Perspectives on Tithing : 4 Views who will not agree with all of the analysis presented here. That is perfectly fine, if you are not completely convinced. All I hope for is that we find ways to extend grace towards others who hold to different views regarding the applicability of tithing for New Testament believers, and acknowledge that this is a matter of Christian conscience.

Notes:

1. This argument about the “pre-Law-of-Moses” nature of tithing is best presented by Hemphill and Eklund in Croteau, pp. 27ff and North in Croteau, editor, Perspectives on Tithing: 4 Views, pp. 141ff and 151ff. However, some tithing advocates strangely argue the opposite, that Abraham was actually keeping the “law,” as described in Genesis 26:5, thus undercutting the notion that Abraham’s act of giving a tithe to Melchizedek was prior to the “law.” The difficulty here is that one wonders how the word “law” is being defined here. For if “law” is the Law of Moses, then this creates a chronological problem in that Abraham lived centuries before Moses. Therefore, whatever “law” is being referenced in Genesis 26:5 can not be the same thing associated with Moses’ activity related to Mt. Sinai. Part of the confusion stems from the idea of the “Law of Moses,” which is actually a very broad concept. For it can mean the “law” which explicitly involves Moses writing down what was given to him personally, or it could mean the “law” associated with the Law of Moses, which would include all five books of the Pentateuch, including Genesis, from where the Abraham story comes is found, and not necessarily specific directives given by God to Moses. In the case of Abraham in Genesis 26:5, this could simply mean particular commands given by God to Abraham personally, but there is no direct connection here with the Melchizedek passage, as Genesis 26:5 is more of a general statement, honoring Abraham’s obedience to God. But it does not specifically address the question of what motivated Abraham to offer a tithe to Melchizedek. See the Veracity blog post which discusses the “Law of Moses.”↩

2. See this previous Veracity blog post about Melchizedek for more about this mysterious figure more generally.↩

3. The most significant Dead Sea Scroll in this context is the Melchizedek document, also called 11Q13, found at Cave 11 at Qumran. The Hebrew word transliterated into English as ma-a-ser is often translated into English as “tithe”, or “tenth”, and is mentioned other times in the Old Testament. Also, a related Hebrew word for “to tithe”, transliterated as a-sar, is found several places as well, as in Genesis 28:22, regarding Jacob’s tithe. But the case of Abraham and Melchizedek in Genesis 14 presents the strongest pro-tithing case for New Covenant believers, as the story is also discussed in the New Testament in Hebrews 7. Some suggest Jacob’s tithe in Genesis 28 was part of regular, ongoing practice. However, the actual text does not offer any evidence in favor of that view, in that only one instance of giving this tithe was mentioned. Furthermore, Jacob’s tithe is not commanded by God, rather it appears to be a voluntary action. These are the same type of problems found in the Abrahamic tithe to Melchiizedek. This blog post series is not intended to be an exhaustive examination of all of the arguments regarding tithing.↩

4. Of the four participant perspectives in the dialogue in Perspectives on Tithing: 4 Views, three of the positions differ on the role of tithing for the New Testament believer, but they all agree that in the New Testament there is some aspect of generous giving involved. Gary North’s position is the only one which insists that the tithe is never associated with being a gift, or otherwise voluntary, but rather it is purely an obligation, and the tithe is always 10%. “The tithe is 10 percent of your net income—no more, no less” (Gary North in Croteau, p. 51.). “The tithe is not the standard of Christian giving. It has nothing to do with giving. The tithe is the God-mandated payment by God’s royal priesthood to higher priests who are formally ordained to defend the church and the sacraments, as surely as the Mosaic temple priests were formally ordained to protect the temple and the sacrificial system” (North in Croteau, p. 93). North also states: “My position is that the new covenant tithe, after the cessation of the Mosaic covenant at the fall of Jerusalem in AD 70, has nothing to do with giving. It has everything to do with paying. You do not owe a gift. You owe a tithe. The other chapters reject my position. They all categorize the tithe under ‘gifts to God‘” (North in Croteau, p. 123). In conclusion, North says: “Pay your tithe. End the guilt” (North in Croteau, p. 125). North’s position relies on guilt to motivate the Christian’s financial contributions to God’s work. Sadly, this is missing the element of grace as the prime motivator for giving. Nor does North pay any serious attention to the exegesis of Croteau who demonstrates that the tithe under the Old Covenant was more like about 23% and not just 10%. It is as though North arbitrarily connects the “tithe” solely to the Levitical tithe supporting the Levitical priesthood, and not to either the Festival or the Charity tithe, and then transfers that Levitical tithe alone to the New Covenant. On the positive side of North’s essay, he associates the tithe more with the notion of covenant, which underscores the importance of loyalty by linking the tithe to an oath (North in Croteau, p. 157). In other words, the paying of the tithe acts as a loyalty pledge towards the God of Israel, under the Old Covenant. The principle of the loyalty oath is carried forward into the New Testament whereby our giving under the New Covenant is an expression of our believing loyalty towards the Messiah. North is correct that making financial contributions to God’s work is an act of demonstrating one’s loyalty to the God of the Bible.↩

5. Some object that simply because the text never tells us about any command of God for Abraham to tithe, or that the text never tells us that Abraham ever tithed again, that this does not preclude any command of God, nor does it preclude any repeated tithing action by Abraham. While these objections do have some weight, it would be incorrect to conclude that Abraham must have received a command from God, and/or that he continued to tithe to anyone repeatedly with regularity. At best, such conclusions should be qualified with a “maybe.” To draw definitive conclusions would be making arguments from silence. For if Scripture wanted us to know these things, then the text would have surely told us. It is much better to base any doctrine of Scripture based on what it says, and not on what it does not say. The pro-tithing proponents in Perspectives on Tithing: 4 Views rely on such arguments from silence. Instead, the evidence we possess in Scripture indicate that Abraham’s tithe to Melchizedek was a one-time, voluntary gift.↩

6. The main purpose of Hebrews 7:1-10 for many commentators is to demonstrate that Jesus, as the Great High Priest, is greater than the Levitical priests. Jesus, as a priest in the order of Melchizedek, is greater than the Levitical priests, who are in the order of Aaron. See George Guthrie, Hebrews: The Expositor’s Commentary, pp. 147ff, and David A. deSilva, Perseverance in Gratitude: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary on the Epistle to the Hebrews, Kindle location 3592ff.↩

7. Hemphill and Eklund in Croteau, p. 31.↩

8. Interestingly, Numbers 31:28-30 does describe specifically what the Israelites should pay as tribute to the Lord when obtaining booty from a successful battle. That percentage is just a little over 1 %, which is much less than 10%. In my reading of Hemphill and Eklund, as well as North, in Perspectives on Tithing: 4 Views, these authors begin with the assumption that tithing is some sort of spiritual principle embedded into reality, and then they read this assumption into the text of Hebrews 7 in order to arrive at their conclusion. In biblical hermeneutics, this practice is called eisegesis; that is, reading something into the text which is not there, as opposed to exegesis; that is, reading something out of the text. Bringing in assumptions outside of the text only makes sense when the exegesis of a text sitting by itself is not sufficient in order to establish its clear meaning. But we must be careful not to bring in such assumptions into our reading of Scripture without sufficient warrant. ↩

9. Melchizedek is a type which points to Jesus, but in Jewish typological interpretation, a type is not the same as that which the type points towards. For example, in Romans 5 when Paul describes Adam as a type who prefigures, or points towards Jesus. Paul is not saying that Adam is Jesus, or that Jesus is Adam. Adam is the type. Adam is the type who points towards Jesus. Likewise, Melchizedek points towards Jesus, but Jesus is not Melchizedek. John Walton, in his commentary on Genesis 14, says that according to the text, Melchizedek is depicted as nothing more than the Canaanite king he is described to be. It is not until the intertestamental period of Second Temple Judaism that his role in Jewish thinking expands, through a typological interpretation, which includes this notion that Melchizedek was a priest who lives forever. Typologically speaking, Melchizedek’s roles as priest and king in Jerusalem fits “the Messianic profile.” See Walton, in the NIV Cultural Commentary on the Bible, p. 458. For a higher critical perspective on the Melchizedek story, at odds with conservative scholars, consult this link. Note that even this higher critical writer sees no need mention any application of tithing, strictly speaking for Christians today, as a necessary conclusion to draw from this text.↩

10. The argument that tithing is a non-superseded command of God relevant for today, since it was established before the Law of Moses was given to the people, is problematic also because there are other practices found in the Law of Moses which were practiced before the actual giving of the Law to the people, such as the practice of Levirate marriage, whereby a brother of a deceased man is obliged to marry his brother’s widow. However, few Christians would say that Levirate marriage is still a binding practice for Christians today. Likewise, one should be cautious before immediately assuming that any “pre-Law” aspect of tithing is therefore binding on New Covenant believers. David Croteau has made this argument .↩

11. See Andreas J. Köstenberger and David A. Croteau, Liberty University SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations, Bulletin for Biblical Research, 16 no 2 2006, p 237-260, Scholars Crossing: Reconstructing a Biblical Model of Giving: a Discussion of Reconstructing a Biblical Model of Giving: a Discussion of Relevant Systematic Issues and New Testament Principles. Köstenberger and Croteau argue that the tithe was to be used to support the sacrificial system, which no longer makes sense in the New Covenant, since the sacrificial system was done away with by the work of Christ on the cross, the once and for all sacrifice for sins (This argument is complicated by the fact that Jewish Christians probably continued to participate in the sacrificial system even after Jesus’ ascension, up until the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE). Köstenberger and Croteau also note that the context as found in 1 Corinthians 9:1-23 suggests that while Paul had the right to receive support from the Corinthians, he gave up that right. If Paul had tithing in mind, it would have introduced a situation quite unlike what is found in the Old Testament, which required tithes to be given to support the priests. Could Paul’s refusal to accept tithes indicate that Paul was abrogating the mandatory aspect of tithing? In other words, would the tithe be longer mandated if a pastor refuses to accept being paid by his flock? (Köstenberger and Croteau, p. 249). Köstenberger and Croteau also suggests that Philippians 4:15-20 also plays a role in Paul’s teaching on giving (Köstenberger and Croteau, p. 256) . ↩

12. Andrew Wilson in 1 Corinthians For You: Thrilling You With How Grace Changes Lives, Kindle location 2611, in his commentary on 1 Corinthians 16:1-13 quotes from the Heidelberg Catechism, to show that Christians during the Reformation considered generous giving to the poor to be part of the weekly worship service: “I regularly attend the assembly of God’s people (i) to learn what God’s word teaches, (ii) to participate in the sacraments, (iii) to pray to God publicly, and (iv) to bring Christian offerings for the poor.” Wilson continues on to outline four basic principles of giving: (1) Make giving a priority in your worship, (2) Giving is not just for the rich, it is for everyone, (3) The amount we give should be proportional to our wealth, and (4) Plan your giving. ↩

13. In fairness, in Perspectives on Tithing: 4 Views, Hemphill and Eklund do encourage developing a heart for sacrificial, grace-motivated giving. But what is perplexing about their position is that they do not see how the Old Testament concept of an obligatory tithe of 10%, at least with respect to the Levitical tithe, conflicts with Paul’s teaching in 2 Corinthians 8-9 about not giving under compulsion. If some particular percentage of giving is obligatory, then then this is a sign of giving under compulsion, which contradicts Paul’s teachings…..Andreas J. Köstenberger and David A. Croteau in their Scholars Crossing: Reconstructing a Biblical Model of Giving: a Discussion of Reconstructing a Biblical Model of Giving: a Discussion of Relevant Systematic Issues and New Testament Principles, p. 260, note 122, makes this statement with supporting evidence: “It has been argued (not in writing) that if teaching on tithing were replaced with ‘grace giving,’ then churches could not survive financially. This pragmatic argument does not hold for many reasons. But the following data suggest that even where tithing is taught, it is not practiced.…” What is the point of preaching something when the likelihood is that the congregation as a whole will not practice what is being preached? A healthy does of realism is needed here. ↩

14. See the previous Veracity blog post concerning the Levitical teachings on mixtures. Christians today often think of the Levitical prohibition against wearing two different kinds of cloth as something totally weird, dumb, or stupid, but it actually served a purpose in the mind of the ancient Israelite, to remind the worshipper of Yahweh that when they approach God they are entering sacred space. ….. There is something simultaneously puzzling and encouraging about Reggie Kidd’s contribution to the Perspectives on Tithing: 4 Views book. In many ways, Kidd’s perspective is not that much different from David Croteau’s post-tithing view. “I think that Köstenberger and Croteau’s ‘grace giving’ principles embody a great deal of wisdom: that giving should be systematic; proportional; sacrificial/generous; intentional; motivated by love, equality, and a desire to bless; cheerful; and voluntary” (Kidd in Croteau, p. 121). If anything Kidd’s perspective suggests that tithing is more of an issue of conscience. The distinction between Kidd’s view and Croteau’s view comes down to how the word “tithing” is defined. Croteau insists that “tithing” be defined not simply as “tenth,” but rather, within the context of how the Hebrew word for “tithe” is used in multiple instances within the Law of Moses. In other words, the tithe under the Old Covenant amounted to about 23% of agricultural or animal husbandry goods. Kidd, on other hand, does not focus as much on exegesis as Croteau does, but rather he rather roughly uses “tithing” and “giving” interchangeably, as his argument is that what is ultimately important about the tithing is the “principle” and not “casuistry.” Nevertheless, Kidd is inconsistent with his use of “tithe” in his essay, sometimes linking the “tithe” to the notion of “tenth” and at other times linking it to giving more generally (Kidd in Croteau, p. 97ff). Frankly, many Christians do exactly the same thing, using the word “tithe” interchangeably with the word “give.” This is understandable, but it can be confusing. Kidd acknowledges that interpreters do not always treat the biblical texts about tithing the same way: “To one interpreter it is clear that tithing is not a command for followers of Jesus under the new covenant, but to the other it is equally clear that tithing is a command for us. Perhaps one writer sees too little here and the other too much. Then again, perhaps both have a point” (Kidd in Croteau, p. 100). As a side note, Kidd relies more on personal anecdotes than the other authors in Perspectives on Tithing. Kidd was an undergrad student at the College of William and Mary, where I work. Kidd’s pastor was Mort Whitmann, an influential bible teacher in the Williamsburg, Virginia community in the 1970s. Kidd acknowledged that the church which Whitmann helped to establish in the 1970s eventually folded, due to not having enough contributors to pay the bills. Frankly, this was partly due to the fact that many in that church were college students who were not in a position to give that much since they were not generating much income yet as college students! The most helpful idea found in Kidd’s essay was the realization that following Christ is all about giving everything we have to follow Christ: “Jesus does indeed call for something more radical than a tenth of our income. He calls for everything” (Kidd in Croteau, p. 105).↩

15. The appendix in Perspectives on Tithing: 4 Views is about the history of tithing during the last 2,000 years of the Christian movement. This would probably require a separate blog post to examine this in detail. However, a few highlights are worth noting. The teaching and practice of tithing was indeed mixed during the earliest centuries of the Christian movement. Clement of Rome, near the year 100 CE, urged that Christians give according to God’s “laws,” but he made no specific reference to tithing. Tertullian in the 2nd century wrote that Christians gave voluntarily to support the work of the church, without any reference to an obligatory tithe. A few early church fathers were either full supporters of tithing, or they were mildly supportive of it, including Cyril of Alexandria and Jerome. In more recent history, both Martin Luther and Charles Spurgeon rejected tithing as a New Testament requirement. Many early English Baptists rejected tithing as it violated the teachings of Hebrews 7:12, ” For when there is a change in the priesthood, there is necessarily a change in the law as well.” The logic of these early Baptists was that God changed the priesthood when Christ came, thereby relegating the tithe as belonging to the Old Covenant and not to the New Covenant. In some cases, a Baptist preacher could be brought up on charges of violating church discipline if they accepted tithes (Croteau, p. 181). Today, various scholars and bible teachers, like Andreas Kostenberger, John Piper, Wayne Grudem, and Sam Storms view the tithe as non-mandatory for Christians. ↩

16. I highly recommend several of David Croteau’s other books, from the Urban Legends series, reviewed here on Veracity. Two other brief articles on tithing, such as William Barcley’s pro-tithing essay, and Tom Schreiner’s “post-tithing” essay, are recommended for extra research.↩