From the Christianity Along the Rhine blog series…

The Veracity blog is normally not a high-traffic website. I am well-aware that long-form blogging does not really generate lots of “clicks.” Social media, like Facebook and Instagram, is way too time consuming and life-draining for me to deal with, anyway. But back in mid-September of this past year (2025), I was shocked to discover that Veracity received over 80 thousand views in just a matter of days.

80,000 views???

I had written a blog post about the supposed “rapture” prediction that caught the attention of secular media algorithms, with lots of Facebook and Instagram pages promoting the idea that Jesus will come to take the church out of the world sometime around September 23-24. A South African YouTuber Joshua Mhlakela had “prophesied” that Jesus would return, telling listeners that he was “one billion percent” sure that the prophecy would become true.

I published my blog post about it on September 20, and somehow Google picked it up as the 3rd or 4th highest ranking Internet resource world-wide on the topic. Never before has something I have written gone so viral before.

We had 80,000 hits in just a matter of days, for a blog that gets just a tiny fraction of that on a typical day. Pretty wild for a blog with less than 200 subscribers.

As one might reasonably conclude, Jesus did not come back during the September 23-24 window. Shockers of shockers, Mhlakela was not deterred, and he ended up reformulating yet another prediction that Jesus would return during another window on October 7-8.

Alas again, October 7-8 passed without any fanfare. No rapture happened. The last I heard, he came up with yet a third date prediction, perhaps October 16-17, that of course, failed again. “Rapture Talk” since then morphed into “Rapture Fatigue.” Date-setting for Jesus’ return is a peculiar hobby that keeps on going despite the obvious, with its popularity waxing and waning over time.

If you completely missed this whole story, and want more detail on it, I highly recommend YouTube apologist Mike Winger’s resources on this topic, where he goes into great and fascinating detail about the lunacy.

In September, 2025, many end-times enthusiasts were waiting for the “rapture” of the church by Jesus…. a “rapture” that never came. What was all the fuss about?

Rapture Talk Gone Wild

Most readers of my blog post were probably just curious as to what the fuss was all about. Just pure curiosity. Others were probably like me, simply annoyed that yet another series of failed prophecy predictions, which have had a 100% failure rate over many centuries, continues to excite people, encouraging some to quit their jobs, give away their money, their cars, or even sell their houses. Such misguided people were thinking that either the September or October rapture event would mean that they did not need such things anymore. What a terrible stain “date setting” has on the integrity of Christian witness!!

Christians behaving badly…. strikes again!!

However, if you read some of the comments I got on my article, you will discover that some commenters/readers were indeed true believers, hanging onto such an illusory prediction which never materialized at any of the “expected” times, despite guarantees of “one billion percent” positive accuracy. When the prophecies failed, the true believers doubled-down on the supposed “truth” of their convictions. Who needs evidence, when you can just believe? Bizzare. Bizarre. Bizarre.

What is it about the mindset of such people who are drawn to such ideas? On the positive side, you might argue that such people have a hope that they will soon be taken into the heavenly presence of the Lord Jesus. Amen to that! However, on the other side, there is the dismay and disappointment which comes when such predictions turn out to be false. Then there is the mindset of such a hardcore believers who come up with ingenious ways to recalculate yet another date, or set of dates.

Why are some people drawn to this kind of “date setting?”

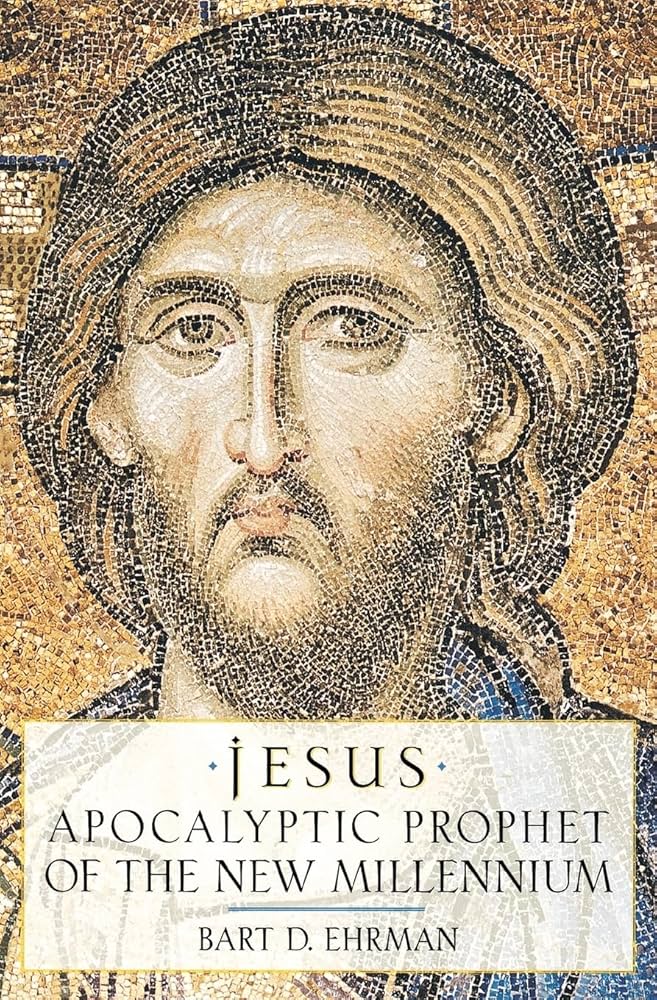

Bart Ehrman’s Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium, raises disturbing questions about the Christian hope for the return of Jesus. But does Ehrman really get the story right?

Jesus as an Apocalyptic Prophet??

I recently read a book by New Testament scholar and professor at the University of North Carolina, Bart Ehrman, which explores this very topic. Ehrman is not a Christian, though at one time he did claim to be one himself, before ditching his faith. Nevertheless, Ehrman remains one of the most recognized scholars on the origins of Christianity, despite his pronounced skepticism.

Before his first New York Times best seller, Misquoting Jesus, came out twenty years ago, Ehrman had published another non-academic book for a popular audience, Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium, back in 1999. Ehrman had been a devout evangelical Christian, who later on went through a period of spiritual deconstruction, only to completely dismantle his own faith in God. Still, he maintained his interest in the study of Jesus and early Christianity, despite having given up on the Christian faith itself. In Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium, he lays out the themes which have undergirded his other academic and popular level books since Misquoting Jesus.

In Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium, Ehrman explains what he sees as the common scholarly consensus from an historical criticism perspective as to who Jesus really was. While more evangelical thinkers like myself will differ substantially in terms of the conclusions which Ehrman comes to, there is still something to be gained from comprehending the basic methodology which stands behind much of the academic study of Christianity taught in most universities today, and popularized by TikTok and YouTube counter-apologists, which Ehrman represents.

Am I a Victim of the “Stockholm Syndrome?”

But why should an evangelical Christian like myself bother to read Bart Ehrman, a vocal skeptic of the Christian faith? Some object that reading works by skeptics will somehow infect your mind and lead you down the path of faith deconstruction. Psychologists do have a name for such mental behavior, the so-called “Stockholm syndrome,” whereby hostages occasionally develop a kind of bond with their captors.

The most famous example from American pop-culture was the phenomenon of Patty Hearst, the granddaughter and heiress of the 20th century media mogul and newspaper owner, William Hearst. At age 20, Patty Hearst was kidnapped by the Symbionese Liberation Army in 1974, only to be filmed a few months later by surveillance video holding a firearm, while she assisted her captors in robbing a bank. Apparently, Ms. Hearst had become so absorbed with the ideology of her captors that she became sympathetic to their cause…. or was she only temporarily deceived and brainwashed?

After Ms. Hearst was captured and arrested by police, she went to jail for her being an accomplice in criminal activity. But she said that once she had gotten away from the mind control of the Symbionese Liberation Army, she finally came to her senses. President Jimmy Carter commuted her prison sentence and she was later pardoned by President Bill Clinton. She ended up marrying her bodyguard, had a couple of kids, and has since been involved in various avenues of charity work, inheriting much of her family’s wealth.

Some think that by Christians reading the work of skeptics like Ehrman that this makes them into potential “Patty Hearst’s.” While this is probably true about some people, I have personally never found the logic behind this argument persuasive for myself. I want to pursue the truth. Too many people simply believe what they have been told by their parents, their schoolteachers, or their church, without ever looking into the evidence for themselves. My mind simply does not work that way.

Patty Hearst, the heiress to the Hearst newspaper enterprise fortunes, was kidnapped by her captors in the 1970s, but within months engaged in a bank robbery. In security camera images, Hearst was holding a machine gun aimed at bank tellers, in support of her captors. Was she a victim of the Stockholm syndrome?

So, if I have come to a conviction about something, the best way to verify that I have come to a valid conviction is to examine the evidence presented by the best representative of an opposing view. For if a conviction I have is actually true, then the conclusion I have reached should be able to stand up to the rigor of the best opposing arguments. The only way to understand those opposing arguments is to actually spend some time examining the arguments and giving the best interlocutor a fair hearing.

There are several reasons why I find Bart Ehrman to fit in that category. For one thing, Ehrman is an excellent writer. Though I disagree with him a lot, I can see why fans of Ehrman love his work, as he is a very good communicator. But more importantly, Ehrman articulates in a very clear way the common scholarly consensus which takes aim at the faith worldview I embrace. Furthermore, Ehrman is widely recognized as a top notch scholar by critics who holds to his views.

The Bart Ehrman and Albert Schweitzer Connection

The foundational argument of Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium is drawn from the work of the early 20th century German biblical scholar Albert Schweitzer. Schweitzer was the 1954 recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, who made one of the first appeals to abolish nuclear weapons. Schweitzer in 1906 wrote the highly influential The Quest for the Historical Jesus. In The Quest, Schweitzer articulates his view that Jesus was a failed apocalyptic prophet. In other words, Jesus appeared on the scene in the first century, preaching a message that God would surely bring judgement on a world which had despised the justice of God and God’s care for the poor and needy. The “end was near” according to Jesus, and Jesus believed that this final judgment and cataclysmic end of the then current world order would happen in no more than a generation.

But that final apocalyptic event never came. Jesus died upon the cross, but no “rapture” type of event happened, according to the expected timeline. According to Albert Schweitzer, Christianity, as an organized faith, developed out of a desire of making sense of how to live with the failure of that prophecy prediction. Instead of abandoning Christianity, the failure of Jesus’ apocalyptic vision to materialize in the first century prompted Christians at that time to double-down on the claim and essentially re-interpret the message of Jesus, in light of this failure of prophecy. This is the basic framework for Albert Schweitzer’s worldview, which Bart Ehrman believes is still the scholarly consensus among those who follow this approach to historical criticism. (Unsure what “historical criticism” is? Check out the Veracity blog series on this topic).

In other words, the whole “Rapture Talk” craze of September, 2025 represents the mindset associated by the thesis as first articulated by Albert Schweitzer, and reiterated in Ehrman’s book on Jesus. It is one thing for a fringe group of professing Christians to get highly animated by extraordinary claims about specific dates for the return of Jesus, and then doubling-down on their ideas when the dates pass by and nothing happens.

But what if Christianity as a belief system itself is infected with this kind of thinking at its very core? Now that becomes a real faith challenge. Can that faith challenge be met with integrity?

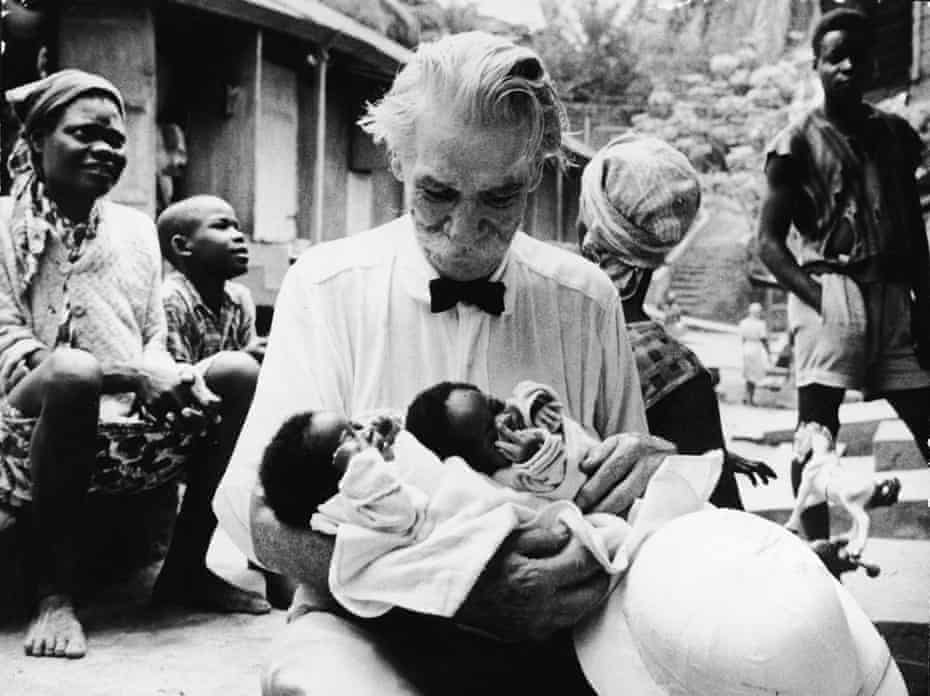

Albert Schweitzer, the famed early 20th century biblical scholar turned medical missionary to Africa, proposed the idea that Jesus was a failed apocalyptic prophet, who predicted the coming end of the world that did not come within the 1st century C.E. Despite this conclusion, Schweitzer continued to consider himself a Christian, and lived out that last half of his life seeking to follow the ethics of Jesus, through generous acts of compassion for poor and needy.

The Legacy of Albert Schweitzer

Was the following just a mere coincidence? I do wonder!

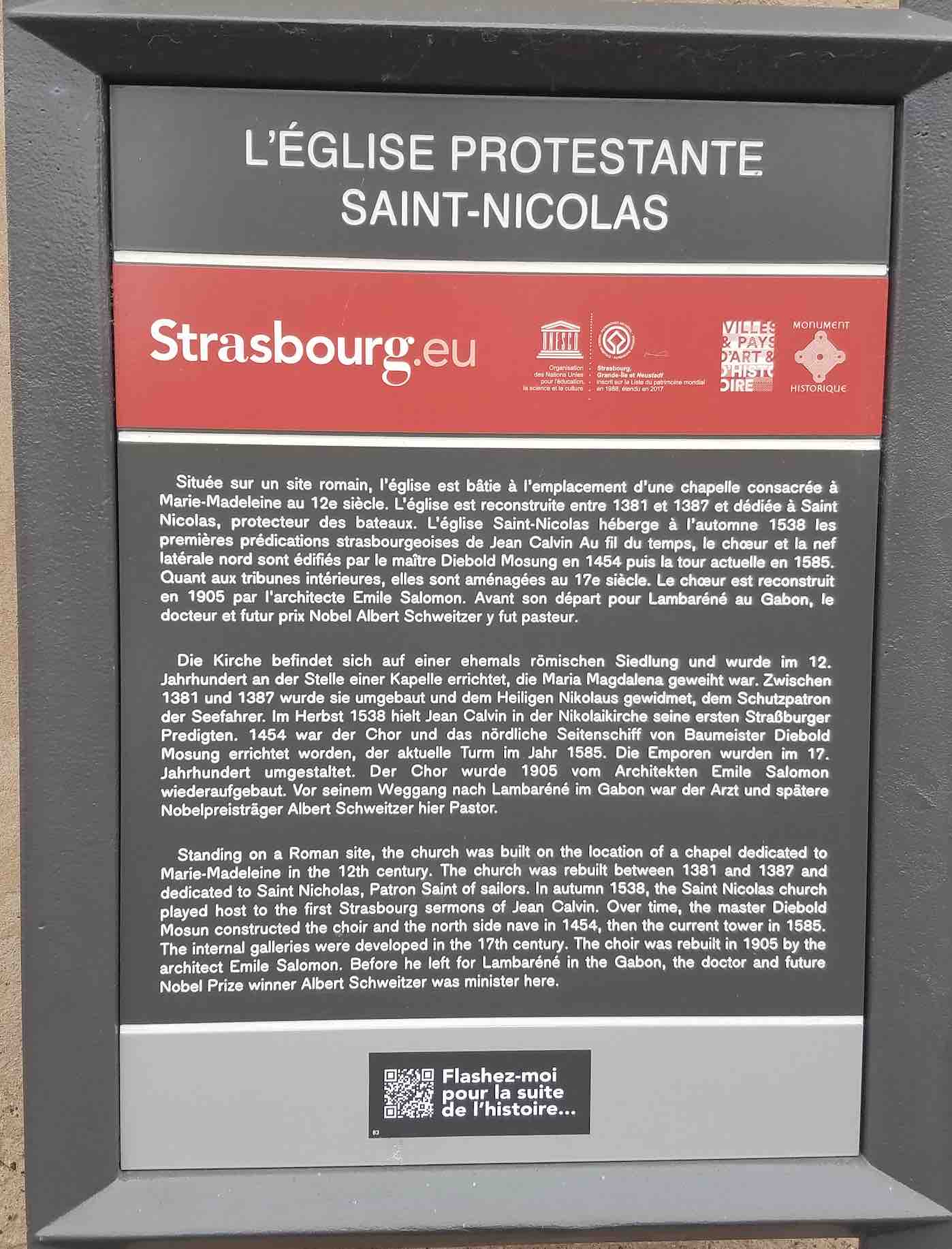

In the fall of 2025, my wife and I took a river cruise down the Rhine River in Europe, and visited the city where Schweitzer preached in St. Nicholas Church and taught at the University for more than ten years, there in Strasbourg. The Protestant reformer, John Calvin, had pastored at St. Nicholas, for a few years to French Protestants living in exile there in Strasbourg, in the 16th century. Nearly 300 years later, Schweitzer was preaching, all while writing and teaching about his belief that Jesus was a failed apocalyptic prophet.

As I wandered around the streets of Strasbourg, strolling about Petite France, in the older part of the city (see photo below). I was listening to the audiobook version of Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium, and Schweitzer’s name came up as I was walking past St. Nicholas Church in Strasbourg. I took a photo of the interpretive signage on the church door (posted below). Until that moment, I had not made the connection that Schweitzer had with the city of Strasbourg. I had to stop listening to my audiobook, and gaze at that church building. That was pretty spooky!

I kept thinking about the diverse paths taken by Schweitzer and Ehrman. Unlike Ehrman, who effectively became agnostic about God, if not effectively a practical atheist, Schweitzer continued to preach at St. Nicholas as a Protestant pastor. But Schweitzer was taking a completely different direction from Ehrman, having concluded that Jesus was this failed apocalyptic prophet, who made a prediction about the “end of the world” which never came. Instead of completely rejecting the faith, Schweitzer still considered himself to be a Christian, though we might best think of him today as a “progressive Christian.”

Both Schweitzer and Ehrman had taken the same methodological approach to “historical criticism.” Both had held to the view that the Bible is not a book, or more properly, a set of books inspired by God. Instead, both had embraced the idea that one needs to bracket off the divine inspiration of the Bible in order to best interpret the Bible as an historical document of human literature. Schweitzer avidly took this approach, but then sought to reinvigorate his approach to the Bible by re-incorporating some notion of divine inspiration after completing his historical critical analysis of the text of Scripture.

But Schweitzer’s career as a Protestant minister and scholar would soon come to an end. Schweitzer eventually abandoned his teaching position at the University of Strasbourg and became a medical missionary, devoting the rest of his life’s work to building a hospital in Africa. Schweitzer, the pastor, became Schweitzer, the liberal Christian humanitarian. By rejecting the notion of a future Second Coming of Jesus, Schweitzer’s denial of this fundamental Christian truth claim led to a kind of erosion of his calling as a church pastor, without a complete rejection of other Christian truth claims.

It should be noted that Schweitzer’s view of Jesus as a failed apocalyptic prophet is actually in contrast to the standard progressive Christian view common in Schweitzer’s late 19th to early 20th century liberal German Protestantism, and progressive Christianity in general today. Ehrman is observant to note this difference. Many such liberals have believed that Jesus preached a social justice-oriented message.

But an historical portrait of an apocalyptic Jesus does not quite square with such a message. For an apocalyptic Jesus, such a progressive message aimed at building a more socially just society was too little, too late. Surely, an apocalyptic Jesus would have sided with the poor and outcast, but with the imminent expectation of a cataclysmic judgment of the world, there would simply be no time left to try to build a more just society. The only thing left would be for people to repent of their wickedness or otherwise face the soon coming judgment of God.

Nevertheless, Schweitzer’s decision to become a medical doctor in Africa took up the progressive cause anyway. Schweitzer abandoned a historically orthodox vision of Christianity, with all of its breadth, for a life singularly focused on service to the poor and needy. The visionary message of an apocalyptic Jesus got transformed in Schweitzer’s mind into a Jesus with a social justice message, dedicated to changing the world over the long haul.

While one can admire Schweitzer’s ethic of following after Jesus’ sense of service to the poor and needy, in my view, Ehrman’s position in comparison is more sensible. Ehrman simply is not trying to believe in some kind of Christian faith based on some form of wishful thinking. Ehrman appreciates Jesus’ moral example, but has no need for what he sees are the metaphysical beliefs which arose within early Christianity in response to the failed apocalyptic message of Jesus. Such metaphysical beliefs include the Virgin Birth, the hope for a future bodily resurrection for believers, and a yet future Second Coming of Jesus to bring about final judgment and restoration of the world. I, on the other hand, as opposed to both Schweitzer and Ehrman, believe these things to be true.

In the early 20th century, Albert Schweitzer preached in Saint Nicholas Church, in Strasbourg, the same church the 16th century Protestant Reformer, John Calvin, preached in a few hundred years before. Calvin’s flock was made up of Protestant refugees fleeing religious persecution in France. After Schweitzer was in Strasbourg, Schweitzer changed the course of his life, giving up evangelical preaching for a life of service as a missionary doctor in Africa. My wife and I visited Strasbourg in October, 2025, and discovered this church. From where I was standing, I could not get the full steeple of the church building in this photo!

Reviewing Bart Ehrman’s Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium

In many ways, my thoughts about Ehrman’s Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium mirror the review given by Neil Shenvi (Part One, Part Two, Part Three, Part Four, Part Five….. As an aside: Shenvi’s Part Five deals with an issue raised by my previous blog post about the Council of Nicaea wrestling with the dating of Easter).

I do not need to repeat much of what Shenvi says, as I would urge Veracity readers to go on over to his blog and read his review for the details. But I do have some comments about why the whole September 24-25 Rapture prediction fiasco and Bart Ehrman’s book related to it is so troublesome.

Those who so confidently claimed that Jesus would return on September 24-25, 2025 were not undeterred by the failure of their prediction. They simply doubled-down on their beliefs and reworked their belief system to make it all fit somehow. Yet this was not the first time false predictions about the timing of the return of Christ have misled people.

When William Miller traveled the eastern seaboard of the United States in the early 1840’s, proclaiming that Jesus would come back in 1843, he was super-confident about it. But when the date passed and Jesus did not return, he simply recalculated and set the new date to 1844. To Miller’s credit, he finally admitted failure after 1844 came and went with no Second Coming of Jesus. Today’s Seventh Day Adventist movement emerged from the ashes of that failed prophecy prediction.

When Charles Taze Russell, the founder of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, predicted that Jesus would return in 1914, and the date passed with no Jesus appearing, he began teaching that Jesus had returned “spiritually,” not physically on earth. The Jehovah’s Witnesses have been recalculating and spinning new predictions for the return of Jesus ever since.

As suggested, Ehrman’s main thesis of Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium is that the failure of Jesus to return in the first century A.D. led the fledgling Christian movement to rework the theology of the church to reflect this new understanding. In other words, the psychological dilemma of a William Miller or a Charles Taze Russell wrestling with a failed prophecy prediction likewise haunted the early Christian movement of the late first century.

In a more recent book by Ehrman, Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife, reviewed here on Veracity, Ehrman takes a step further than Schweitzer by arguing that with the failed apocalyptic prophecy of Jesus, the early church simply replaced that failed prophetic expectation with the belief in hell as conscious eternal torment. This is quite an ingenious yet problematic claim, but part of another discussion best left to some detailed analysis in some future blog post series, which I have not taken on yet.

Nevertheless, there is a grain of truth to Ehrman’s argument. The Apostle Paul in 1 Thessalonians 5 sure sounds like he expected the return of Jesus to happen within his lifetime. One of Ehrman’s primary prooftexts in Mark 13:30, where towards the end of the Olivet Discourse in Mark 13, Jesus says:

“Truly, I say to you, this generation will not pass away until all these things take place”.

Jesus had been predicting a number of cataclysmic things, as in verses 24-25:

“But in those days, after that tribulation, the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light, and the stars will be falling from heaven, and the powers in the heavens will be shaken.”

Since nothing this cataclysmic happened, Ehrman concludes that Jesus made a failed prediction about the end of the world coming within a generation of his uttering these words. With the failure of the prediction, the “true believers” of Christianity had to come up with a way to make sense of this failure in order to keep the Christian movement going. Frankly, if this thesis is correct, I can see why someone like Albert Schweitzer had to somehow re-envision a completely reworked understanding of Christianity and why Bart Ehrman ultimately rejected the faith altogether.

A sign on the side of Saint Nicholas Church in Strasbourg, France, indicates that Albert Schweitzer once served as a pastor here (the bottom paragraph in English). It was during the time of his pastorate at Saint Nicholas Church where he further developed his ideas of Jesus as a failed apocalyptic prophet. Schweitzer’s vision of a “progressive Christianity” shows how far he moved away from historic orthodox Christianity.

An Alternative to Bart Ehrman’s Skepticism

But was the “end of the world” in the most physical way possible what Jesus was describing here, or is there something else going on? Some suggest that what Jesus meant by “this generation” is either some reference to “the human race,” “the Jewish race,” or to some future “this generation” when the end of the world really takes place. My old NIV 1984 version of the Bible I had in college had the alternative, rather ambiguous translation for “this generation” as “this race” in a marginal note. While some Christians have held to such arguments, I would argue that there is a more compelling way to interpret what is going on here (See Part 4 of Neil Shenvi’s review of Ehrman’s book which makes a very similar argument to mine).

In the first verse of the passage, Mark 13:1, one of Jesus’ disciples points out the grandeur of the Jerusalem Temple as they pass by it. Yet in verse 2, Jesus says that the great stones of the Temple will fall: “There will not be left here one stone upon another that will not be thrown down.” This explicit statement by Jesus should frame the whole narrative, showing that Jesus was predicting the destruction of the Temple.

As was indeed common in apocalyptic literature of the day, using language like the “sun will be darkened” and the “stars will be falling from heaven” were pregnant images about a great catastrophe coming. This was not unique to Christianity. Jewish apocalyptic literature during the period, whether in the Old Testament or outside of it, made a lot of use of such vivid imagery. Furthermore, for first century Jews, the destruction of the Temple was indeed a great catastrophic event…. but not the literalistic “end of the world as we know it,” as the 1980s/1990s band REM sang about.

Petite France is the most historic district in Strasbourg, just a few blocks down the street from Saint Nicholas Church, where Albert Schweitzer pastored in the first decade of the 20th century….. When Schweitzer lived in Strasbourg, the city was under German control. When Germany was defeated during World War I, it reverted to French control. Strasbourg has a long history of being in a perpetual identity crisis: Is it German or French? Today, this part of Strasbourg (now in France) is a favorite tourist spot, with plenty of shops where you can spend your money. We bought some shoes for my wife near here, as the walking shoes she brought to Europe were worn out!!

The Destruction of the Temple as the Apocalyptic Event Jesus Predicted

Ehrman’s appeal to this passage is too literalistic. In many ways, the destruction of the Temple was an “earth-shattering” event, to use a more modern figure of speech. But this need not imply the actual shattering of the physical planet earth. Instead, Jesus was using apocalyptic metaphors to express what would happen, as opposed to some wooden non-metaphorical language.

One can reasonably conclude that the destruction of the Temple, a prediction which Jesus did make which actually did come true, could also function in a typological way. A typological approach to prophecy was not unique to the New Testament and early Christianity. The literature of Second Temple Judaism made significant use of typology. Just consider the “day of the Lord” language you read in several of the Old Testament prophets, like Isaiah and Amos. God used the nations of Assyria and Babylon as types of judgment against Israelites, anticipating a future great “day of the Lord” yet to come.

In other words, the destruction of the Temple would serve as a type of great cataclysmic event that has yet to happen. This great future event, yet to happen, fits in better with Paul’s expectation of the return of Christ. While Paul appears to believe that the return of Christ was imminent, say in 1 Thessalonians, when you read some of his later writings, such as the Pastoral Letters (1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, Titus), it would also appear that his thinking had shifted, the closer he was to his own death. Perhaps there was a delay, the specifics of which were not revealed to him, and he would die before Jesus’ return.

Instead of an end that was just right around the corner, Paul anticipated the need for the church to have a governing and leadership structure, as with the selection of elders and deacons, who could carry on the ministry that the apostles originally set forth on into the next generation, assuming there was a possible delay. For if Paul never considered a possible delay, it would not have made any sense for Paul to try to establish such a leadership structure, which he instructed to Timothy and Titus.

Even Paul’s second letter to the Thessalonians indicates that the apocalyptic language of the New Testament has at least some metaphorical element, which fits in well with a typological interpretation of “the end of the world.”

Now concerning the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ and our being gathered together to him, we ask you, brothers, not to be quickly shaken in mind or alarmed, either by a spirit or a spoken word, or a letter seeming to be from us, to the effect that the day of the Lord has come (2 Thessalonians 2:1-2 ESV).

The cataclysmic language associated with “the day of the Lord” can hardly mean an end to the space-time universe, as Paul evidently believes that it would have been possible for the Thessalonians to have received a letter (not even an email, or a Facebook post, mind you!!) to have announced that “the day of the Lord” had arrived. This is far less cataclysmic than some kind of global nuclear holocaust. For if the “end of the world” would happen tomorrow, I would hardly need to wait for a snail-mail letter to arrive in my mailbox to find out about it.

However, if what Paul had in mind was a type of “day of the Lord,” as in the destruction of the Jerusalem temple, which happened a few years after his death, which could function as a typological prefigurement of the final “day of the Lord,” which historically orthodox Christians associate with the Second Coming of Jesus, an event which has yet to come, then the data fits! Therefore, it would be reasonable to conclude that Paul expected some type of non-literal-cataclysmic “day of the Lord,” within the first century, which still anticipated a final, future cataclysmic event, which in our lifetimes some twenty centuries later, has yet to come.

I would suggest that this interpretation of Scripture would also explain Peter’s way of thinking expressed in Second Peter, an argument I have made elsewhere.

In response, Ehrman believes that 2 Thessalonians was a forgery, written in the name of Paul, which gets him out of this pickle. For Ehrman’s proposal to work, it would make sense for Paul to have expected the return of Jesus within his lifetime, as some have understood from 1 Thessalonians. However, some time later, after Paul’s death, someone drafted up “2 Thessalonians” to sound like Paul, but making this supposed Paul issue some “correctives” to the “Jesus’-return-is-right-around-the-corner!” type of thinking associated with 1 Thessalonians. But if the traditional claim, that indeed 2 Thessalonians is authentically Pauline, is correct, then a typological reading of the “day of the Lord,” looking forward to the final return of Christ is still a more probable interpretation of Paul’s thinking.

Instead of being a failed apocalyptic prophet, as Ehrman suggests, the opposite is true. Jesus is the true prophet who predicts the destruction of the Temple, which typologically looks forward to the eventual return of Jesus, who will come to judge the world and finally set everything right.

A Sober Warning: Wishful Thinking Works Both Ways

Unlike the misguided attempts at “date setting” for the return of Jesus, responsibly-minded Christians can live with the hope and sober expectation that Jesus will return at any moment, according to his timing, where our job is not to waste time and energy coming up with trying to predict dates. Instead, we should be about doing the work to which Jesus has called us to do, that is, to make disciples of all the nations.

There is a sober warning I picked up from Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium that serves as a lesson for Christians today. The famed Christian humanitarian Albert Schweitzer had come to the conclusion that Jesus was a failed apocalyptic prophet, though he still to sought live as a Christian should, by pursuing a life dedicated to serving the poor and needy. True, serving the poor and the needy is indeed part of the Christian calling. However, the problem with Schweitzer was that he nevertheless was pretending Christianity to be something which he intellectually concluded was not true. For it makes no sense to think that Jesus was about serving the poor and needy over the long haul, if indeed the “end of the world” was right around the corner, as Schweitzer concluded was the essence of Jesus’ message. In Schweitzer’s thinking, there was no “long haul” for Jesus, but we should still live as though there is a “long haul” anyway. That is just a case of wishful thinking gone awry.

Likewise, those “Rapture Talk” enthusiasts of September 23-24, 2025 have done the same thing that Schweitzer did, just in the opposite direction. Jesus’ use of metaphorical language to express his apocalyptic message is an idea that such enthusiasts would never counsel. Instead, they would want to be as literalistic as possible, despite what the evidence shows. They so desperately wanted Jesus to come back in a specific way that they read the Bible in a manner that already fit their picture of what they wanted the Bible to say. When the evidence of their false predictions became apparent, they chose to double-down on their wishful thinking paradigm anyway.

Like Albert Schweitzer, “Rapture Talk” enthusiasts chose to pretend the Bible says something, which it does not. They just took a hyper-conservative path, instead of Schweitzer’s progressive Christian path.

Bart Simpson apparently went around proclaiming that the end of the world was near. Do some people today have a cartoonish vision of what Jesus’ message was about today?

Other Problems With the “Jesus the Failed Apocalyptic Prophet” Thesis Examined

Scholars sympathetic to Ehrman’s thesis will sometimes push-back and say that Jesus did not predict the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, claiming that the early Christians wrote that story into the Gospels and put those words on the lips of Jesus. But if indeed the Gospel of Mark was written prior to the year 70, when the Temple was destroyed, it is reasonable to assume that this was an actual prediction made by Jesus that did, in fact, become true. The argument against the authenticity of Jesus’ sayings here is mostly drawn from an anti-supernatural bias which rules out a priori the concept of predictive prophecy. This kind of anti-supernaturalism is all a part of Ehrman’s flawed thesis.

To his credit, Ehrman is willing to engage the arguments of other scholars, even those others who are skeptical of historical orthodox Christianity, who do not accept the Albert Schweitzer thesis. For example, John Dominic Crossan, a former Roman Catholic priest, and self-proclaimed “progressive Christian,” believes that Jesus was not an apocalyptic prophet at all. Instead, the idea of an apocalyptic Jesus was actually an invention of the early church, which arose during the time when the canonical Gospels were written.

Crossan makes the ingenious argument that our four canonical Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John), are not our earliest accounts of Jesus’ life and ministry. Crossan believes that texts like Gospel of the Hebrews and the Gospel of Peter, which lack the kind of apocalyptic material we find in texts like Matthew, Mark and Luke, predate the canonical Gospels.

Elsewhere, Crossan has suggested that the Gospel of Peter, which contains a narrative of the death of Christ, utilized a source which predates the canonical Gospels. Along with the Gospel of Thomas, which is a collection of the sayings of Jesus, which Crossan also dates to being prior to the canonical Gospels, these alternative texts envision a non-apocalyptic Jesus (Crossan discusses some of these ideas in various YouTube videos, including this one).

The main problem with Crossan’s thesis is that the Gospel of the Hebrews and the Gospel of Peter are never mentioned in the historical record prior to the very end of the 2nd century, whereas the vast majority of scholars date the canonical Gospels to much earlier (You can read more about these other texts from an earlier Veracity blog post).

Crossan’s thesis suggests that the more apocalyptic texts, like Mark, appeared as creations derived from a text like the Gospel of the Hebrews (Ehrman, chapter 8). Ehrman is correct to reject such a thesis as a form of special pleading, an effort to redate texts like the Gospel of the Hebrews without evidence in order to support one’s views. So, while there is still much to disagree with Ehrman in his book, Ehrman is still right to call out speculation from those like John Dominic Crossan as entirely fanciful.

There are other chapters in Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium which offer helpful background material about the life, ministry, and teaching of Jesus. Even though I find Ehrman’s fundamental thesis to be flawed, there is still much to be gained from his book. However, in reading some of his more recent books, reviewed elsewhere here on Veracity, I have learned that these more recent books go into more detail into Ehrman’s thought. But for someone who wants a more succinct, broad-minded understanding of who Ehrman thinks Jesus really was, as a representative survey of how many (though certainly not all) modern critical scholars view Jesus, Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium will serve as a helpful resource.

In the end, I would say that Ehrman’s thesis comes up short. While the Gospels surely all share an apocalyptic theme, this need not imply that the early Christian church had to somehow reinvent the Christian message once the “End Times” failed to materialize during the lifetimes of Jesus’ earliest disciples. There is better explanation for the delay of the “End Times” than what Ehrman proposes. Therefore, let us be about living the message of Jesus, serving the poor and needy, while proclaiming the Good News of the Gospel, while we await Jesus’ return. As Christians, we should continue to uphold the phrases found in the Nicene Creed, which summed up the beliefs of historic orthodox Christianity, that Jesus indeed will return, though without a need to try set any dates: “He will come again in glory, to judge the living and the dead, and his kingdom will have no end“.

January 21st, 2026 at 3:51 pm

New Testament scholar Dale Allison is like a modern day Albert Schweitzer; that is, a progressive Christian who believes that Jesus was a failed apocalyptic prophet:

LikeLike

February 4th, 2026 at 9:53 pm

Have you read any of Ian Paul’s blog? There he argues for example that most of Matt 24 is about the 1st century and not Jesus’ return. He makes some strong points.

LikeLike

February 4th, 2026 at 11:42 pm

Hi, PC1. Yes, I am familiar with the Psephizo blog that Ian Paul writes. I have not read specifically his comments about Matthew 24 (if you have a link to that, would you mind posting that here??), but I know about his views on the Book of Revelation, which are pretty close to mine, which ties into the idea that Matt 24 is primarily about the 1st century, and not Jesus’ return. Ian Paul’s position is most similar to that of F.F. Bruce and N.T. Wright, who argue pretty much the same thing, as the case I have laid out here. Thank you for mentioning this!

LikeLike