In our New Testament, we have 27 books, which include 4 Gospels. However, from about the second century and onwards for a few hundred years, a number of other competing gospel texts emerged (along with other letters), seeking attention from Christians hungry to know more about the faith. But among these “lost scriptures,” were any of these writings legit?

In historically orthodox circles, there was unanimous agreement that Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John were the official gospel accounts, describing the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth, dating back to the first century. Luke himself acknowledged that “many” (Luke 1:1) have sought to write gospel accounts about Jesus. So, what happened to these “many” alternative gospel accounts?

It is reasonable to say a number of these “many” accounts were probably lost, partly perhaps due to the turmoil caused by the Jewish Wars of the 66-70 CE, culminating in the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, and later during the Kito War impacting the Jewish community in Alexandria starting around 115 CE, as well as the Bar Kokhba Revolt in the 132 CE. Thousands and thousands of Jews died in these conflicts, which probably included a number of Jewish Christians. As the original Christian community of the first century was primarily Jewish, there is a good chance that a number of these “many” writings perished along with those who wrote or sought to preserve them.1

Sure, many Christians know that we have 66 books in the (Protestant) Bible, and in particular, the 27 which make up the New Testament. But what about those books from the early church era that did not make it into the New Testament? What were these books and what were they about?

What “Lost Gospels” Did Not Make the Final Cut Into the New Testament, and What Were They?

While none of these supposed “lost gospels” from the first century are known to us today, scholars nevertheless acknowledge that a number of other supposed gospel accounts can be dated back to as early as the 2nd century CE. However, for the most part, these writings have been lost for most of church history, except in cases where a church father quotes from such documents.

Nevertheless, there have also been spectacular re-discoveries of some of these documents that were thought to be lost, as with the 1945 recovery of the Nag Hammadi Gnostic Gospels recovered in Egypt, including the well-known Gospel of Thomas. It seems like every few years or so, a new discovery is made, as with the Gospel of Judas.

These gospel accounts which did not make it into the New Testament canon are generally called “apocryphal gospels,” where “apocryphal” describes something of questionable or unknown origin. Some apocryphal gospels have sought to tell a different version of Jesus’ story at variance from the four official accounts, which primarily explains why these texts were rejected by the historically orthodox of the early church, along with the late dating of such writings which put them out of reach of being written and/or authorized by the earliest Christian apostles, or anyone else in that apostolic circle.

In addition, yet another group of apocryphal gospels were written not to attack the official narratives, but rather to fill in the gaps perceived to be missing from Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. One popular apocryphal gospel like this that did survive from about 2nd century is the Protoevangelium of James, otherwise known as the Gospel of James, examined briefly here before on Veracity, which goes into considerable detail about the life of the Virgin Mary, including elements which are not reported anywhere in the four canonical Gospels.

The Gospels in our New Testament primarily focus on the public ministry of Jesus, a period generally thought to have lasted three years when Jesus was an adult. Of that material, our Gospels spend the most amount of time on the last week of Jesus’ life, including his crucifixion and subsequent resurrection. John and Mark completely ignore anything about Jesus prior to his public ministry as an adult.

The same could be said about writings such as the letters of Paul. Scholars have known for years that there must have been other letters between Paul and the Corinthians that never made it into our New Testament. As a result, curious Christians wanted to know more about what happened to those lost Corinthian letters, the lost letter to the Laodiceans, as well as a desire to understand something more about Jesus’ childhood, etc. Were there other gospels, lost letters, etc? What else was available to fill in those gaps?

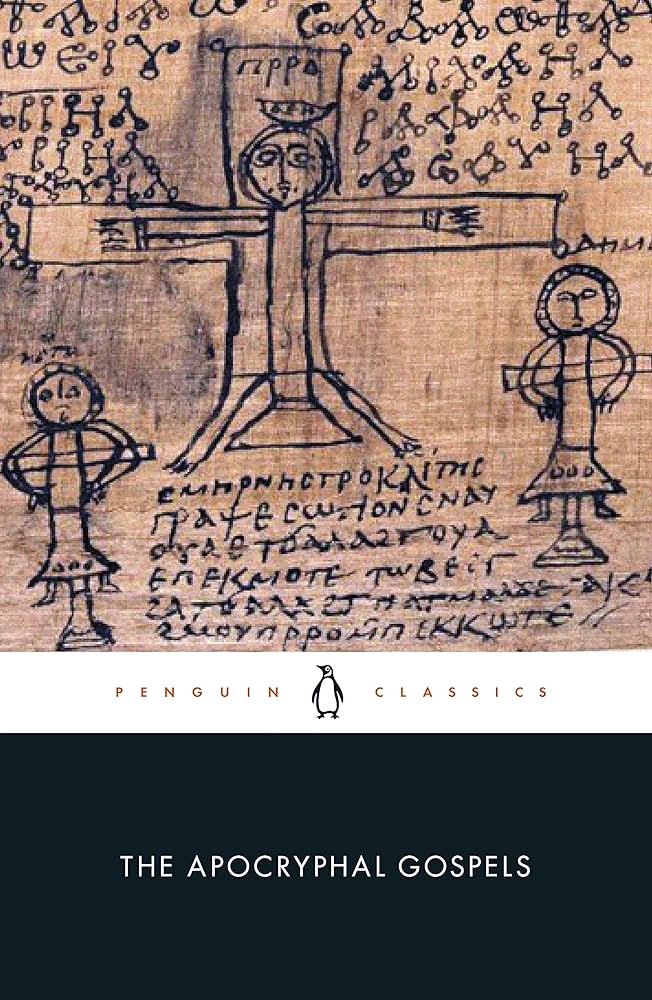

The Apocryphal Gospels, part of the Penguin Classic series, was written by Cambridge University (U.K) scholar Simon Gathercole. Gathercole translates a number of alternative gospel accounts from the early church era, that are not found in our New Testament.

Apocryphal Gospels and Lost Scriptures

After I had the privilege of meeting Dr. Simon Gathercole in Cambridge in January 2024, I picked up a Kindle copy of his The Apocryphal Gospels, a collection of many of these non-canonical gospel accounts. A devout evangelical Christian scholar, Gathercole assembled this book together for the publisher, Penguin, as an aid to study the differences found between the apocryphal gospels and Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Unfortunately, Gathercole’s work is not available as an audiobook, which is how I have been largely reading books, while on my commute to and from work.

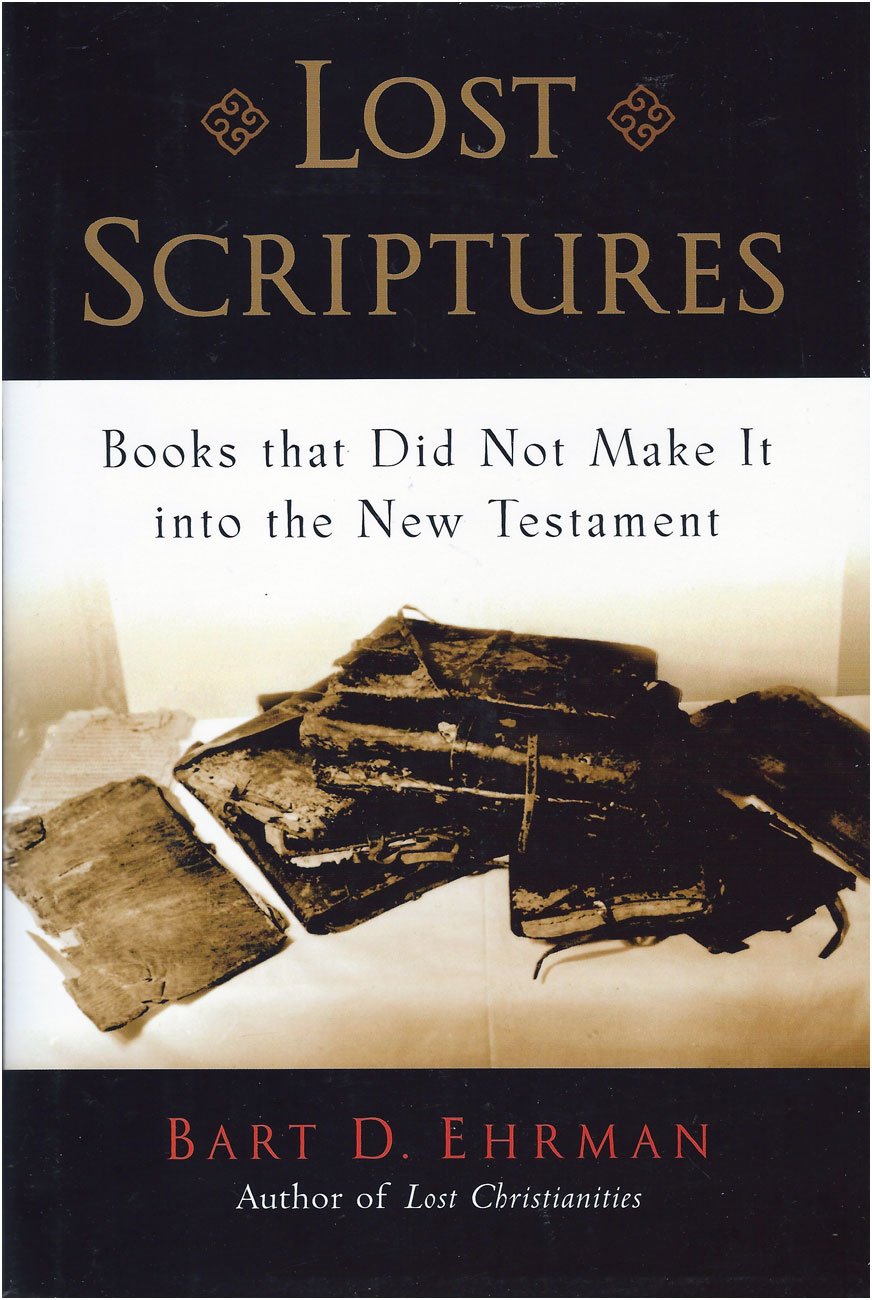

Instead, University of North Carolina biblical scholar, Bart Ehrman, does have his collection of apocryphal gospels, Lost Scriptures: Books that Did Not Make It into the New Testament, available on audiobook, so I gave Ehrman’s work a listen. Ehrman does not include certain apocryphal gospel fragments which Gathercole does. But Ehrman does include other non-canonical apocryphal New Testament texts which are not gospels, such as various letters and narratives claiming to have been written by those like Peter and Paul, but which scholars generally acknowledge today as forgeries.

Both Ehrman’s Lost Scriptures and Gathercole’s The Apocryphal Gospels are collections of diverse material, and therefore are more useful as reference works. Nevertheless, I wanted to listen to Ehrman’s book, and occasionally compare Gathercole’s work along the way. Both Ehrman and Gathercole give their translations of the whole of the surviving documents, when such texts are fairly short, while in some cases only providing a sample or even just an outline of those certain texts which are quite lengthy.2

Lost Scriptures That Sound Strange in Places

Some things you find in these apocryphal New Testament texts are fairly benign, whereas some other things are quite strange, counter to what you find in the canonical New Testament. Take the Gospel of the Egyptians, dated to the 2nd century, for instance. What we have of this gospel only exists from quotations found in the writings of the early church father, Clement of Alexandria. The Gospel of the Egyptians evidently contained a narrative detailing a conversation Jesus had with Salome, one of the women who first witnessed the Resurrection of Jesus.

Ehrman gives us saying number one as follows (Ehrman, p. 19)

When Salome asked, “How long will death prevail?” the Lord replied, “For as long as you women bear children.” But he did not say this because life is evil or creation wicked; instead he was teaching the natural succession of things; for everything degenerates after coming into being. (Clement of Alexandria, Miscellanies, 3, 45, 3)

That is not terribly strange. But here is Ehrman’s translation of saying number four (Ehrman, p. 19)

Why do those who adhere to everything except the gospel rule of truth not cite the following words spoken to Salome? For when she said, “Then I have done well not to bear children” (supposing that it was not suitable to give birth), the Lord responded, “Eat every herb, but not the one that is bitter.” (Clement of Alexandria, Miscellanies, 3, 66, 1–2)

According to Simon Gathercole, statements like these in the Gospel of the Egyptians were used as rationale for denigrating sexual relations and the having and raising of children (Gathercole, p. 179-180).3

Then we have Ehrman’s translation of saying number 5, drawn from the writings of Clement of Alexandria:

This is why Cassian indicates that when Salome asked when the things she had asked about would become known, the Lord replied: “When you trample on the shameful garment and when the two become one and the male with the female is neither male nor female.” The first thing to note, then, is that we do not find this saying in the four Gospels handed down to us, but in the Gospel according to the Egyptians. (Clement of Alexandria, Miscellanies, 3, 92, 2–93, 1)

Ehrman comments that the reference to the “shameful garment” to be trampled upon is a Gnostic idea that the human body itself is so utterly infiltrated with evil that it must be discarded before salvation can be realized (Ehrman, p. 18). Gathercole sees this also as a rejection of marriage (Gathercole, p. 179). Both of these ideas, the Gnostic despising of God’s good creation and the rejection of the institution of marriage are considered as heretical teachings by those within the tradition of historically orthodox Christianity.

Then there are texts like the Gospel of the Hebrews, for which only a few fragments have survived. Gathercole states that this was perhaps originally an edited version of the canonical Gospel of Matthew, with a few extra bits of narrative and sayings not found in Matthew. For example, the Gospel of the Hebrews includes the story of the woman caught in adultery, found only in most Bibles today in the canonical John 8.4

But there is some oddball stuff in the Gospel of the Hebrews, generally dated to the second century. For example, the Gospel of the Hebrews has Jesus saying that the “Holy Spirit” is his “Mother” (Ehrman, p. 16), which probably partly explains why the Christian church rejected its authenticity.

Gathercole quotes a fragment whereby Jesus questions his need for baptism, which raises other interesting questions:

The Lord’s mother and brothers said to him, ‘John the Baptist is baptizing, for the forgiveness of sins. Let’s go and get baptized by him.’

‘What sin have I committed,’ Jesus asked them, ‘to have to go and be baptized by him? That is, unless perhaps what I have just said was an unintentional sin! (Gathercole, p. 163-164).5

Lost Scriptures: Books that Did Not Make It into the New Testament, by University of North Carolina New Testament scholar Bart Ehrman, offers a complement to Gathercole’s selection of New Testament apocryphal writings, including various letters, notably some associated with Gnostic Christianity. The photo on the cover of Ehrman’s books features texts from the Nag Hammadi library, a collection of Gnostic scriptures rediscovered in Egypt in the 1940s.

The Gospel of Peter, With Its Talking Cross….and The Gnostic Gospels

The Gospel of Peter stands out as one of the oddest “lost gospel” accounts, in that it features gigantic angelic figures and a talking cross. The Gospel of Peter also tries to portray Pontius Pilate, as representative of the Romans, as being a friend of Jesus, and places the blame for Jesus’ death squarely on the Jews, a theme that has sadly fed into antisemitic attitudes emerging at various times throughout church history, in otherwise Christian communities. This feature has led scholars to conclude that the Gospel of Peter was a second century document, corresponding to the period where the Jewish and Christian communities clearly came to a “parting of the ways,” when the number of Jewish adherents to following Jesus dropped off sharply. Like several of these other “lost gospels,” the Gospel of Peter was eventually rejected during the early church era, and largely forgotten, until a fragment of it was rediscovered in the 19th century, in the tomb of an Egyptian Christian monk.

But most of the non-canonical gospels are associated with the heresy of Gnosticism, many of which belong to the Nag Hammadi library. The Gospel of Philip and the Gospel of Truth both contain esoteric sayings of Jesus, which promote the idea that one must be initiated into the secret knowledge of Jesus’ teachings, which the historically orthodox tradition of Christianity is accused of neglecting and suppressing. In Gnostic Christianity, the pivotal episode found in the canonical Gospels of Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection is either downplayed or entirely neglected.

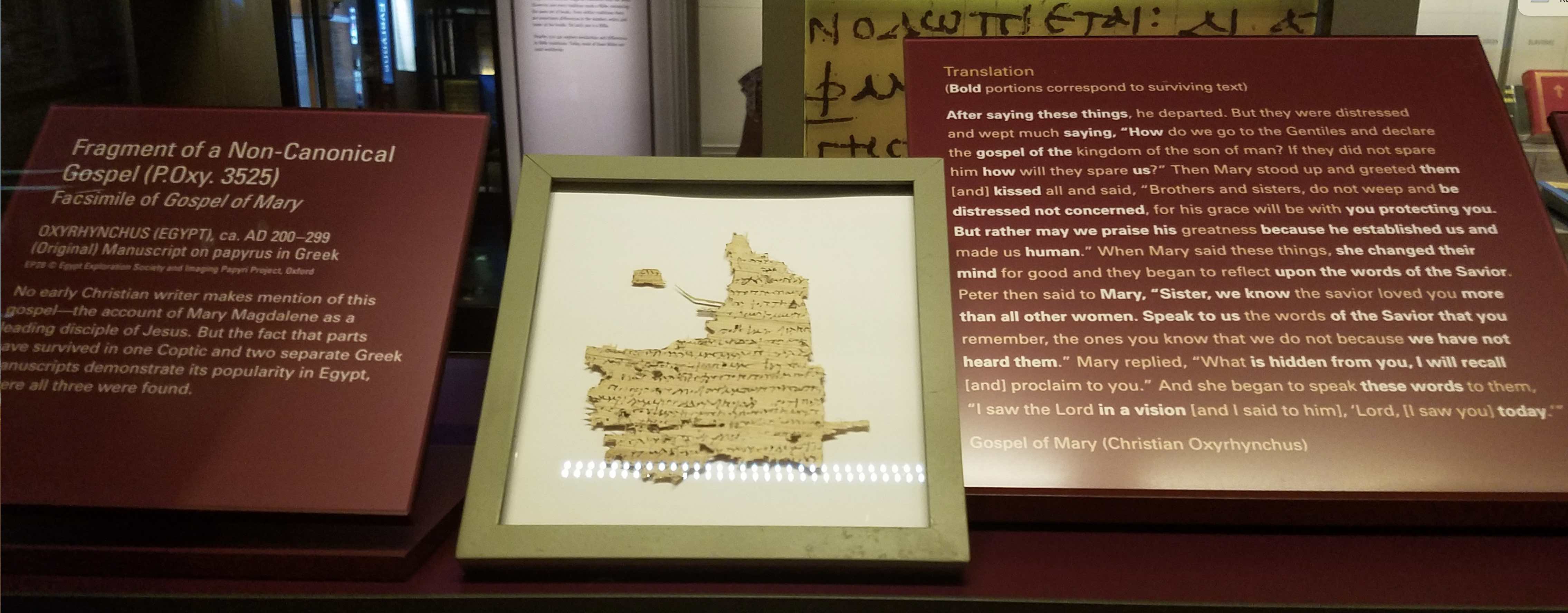

The Gospel of Mary, which was recovered in the late 19th century, has a strong Gnostic element as well, mixed with a proto-feminist message. In the Gospel of Mary, Mary Magdalene has received certain secret teachings from Jesus which were never imparted to Peter. Mary describes a vision she received from Jesus about the ascension of the soul. Peter listens but is not buying into the vision. One of the other male disciples of Jesus (Levi) then rebukes Peter for his macho-masculinity, making Mary the hero of the story and silencing Peter. While the feminist message is largely unique to this gospel, the dialogue displays a common feature of Gnosticism theology, in that the authority of the apostolic community, typically represented by the male twelve in Jesus’ inner circle, is rejected in favor of obtaining esoteric spiritual knowledge.6

Some of the more frustrating examples of “lost gospels” include forgeries written by “supposedly” historically orthodox Christians who wrote books trying to undermine heresies. I put “supposedly” in air quotes as it baffles me why some Christians would resort to writing forgeries in order to combat the writing of forgeries. For example, the Epistle of the Apostles was written probably in the 2nd century to refute certain well-known Gnostic Christian teachers of the late first and early second century, like Simon Magus and Cerinthus. It is just bizarre to think that some proto-orthodox Christian would take a tactic used by the Gnostics to then turn around and use it to refute those same Gnostics.

There are apparently several Apocalypses of Peter, one of them being the relatively popular work which it goes into explicit detail regarding the horrors of hell, which was even listed in the famous and orthodox Muratorian Fragment as being part of the accepted list of New Testament Scriptures, though this particular Apocalypse of Peter was ultimately rejected by the early church as being non-canonical. Bart Ehrman in his Lost Scriptures, in addition to this Apocalypse of Peter, includes yet another Petrine apocalypse, a Gnostic version known as the Coptic Apocalypse of Peter.

Ehrman also includes The Second Treatise of the Great Seth, which like the Gospel of Basilides (not included in Ehrman’s collection) emphasizes that Jesus of Nazareth was not crucified on the cross. Instead, Simon the Cyrene was mistakenly crucified in place of Jesus, while Jesus who escapes his execution laughs at the situation. This denial of the crucifixion of Jesus eventually made its way into the teaching of Islam. The idea behind the crucifixion “mix-up” claim is based on one particular Gnostic Christian belief that it would be impossible, even laughable, for God to have been crucified on a cross. The “Great Seth” is thought by some to be Jesus as the incarnate version of Adam and Eve’s third son, Seth.

A fragment of the Gospel of Peter found at Akhmim, in 1886. This copy has been dated to about the 8th or 9th century, C.E. The Gospel of Peter was rejected as being apocryphal by the early church, and therefore not appropriate for inclusion in the New Testament. It is most known for a reference to a “talking cross,” following the resurrection of Jesus.

Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles

Simon Gathercole’s collection focuses solely on various “lost gospels,” whereas Ehrman’s collection goes beyond “lost gospels” to include various “Acts” of the Apostles, but not the stories contained in the New Testament Book of Acts. Ehrman includes texts like these:

- The Acts of John: John the son of Zebedee is the main character here, but this is a Gnostic text, with some odd-ball stories in it, such as about a bed John is sleeping in, which is infested with bedbugs. The miracle stories presented in the Acts of John are generally way overdone, sensationalist, and some downright absurd. One story is about a man, assisted by an accomplice, who breaks into the tomb of a dead woman whom the man lusted after, intent on having sexual relations with the corpse. The intended rapist is killed by a serpent. John then resurrects both the woman and the man. Jesus is described in ways that suggest that he never had a flesh and bones physical body. I was quite happy to be done with the Acts of John when I finished!

- The Acts of Paul: Ehrman has an extract detailing how Paul was beheaded by Nero in Rome. The second century church father Tertullian knew of the Acts of Paul, as having been forged by a presbyter living in what is now modern-day Turkey, who wrote this book “out of love for Paul.”

- The Acts of Thecla: Thecla was thought to be a well-known female disciple of Paul, and the book was quite popular even into the Middle Ages. Thecla breaks off an engagement to be married in order to follow Paul, which causes all sorts of problems for her. The Acts of Thecla were often circulated together with the Acts of Paul. While it is difficult to establish the historicity of these accounts, there is good reason to believe that Thecla was a real person, featuring one of the few in-depth stories from the earliest Christians about the piety of a female follower of Jesus.

- The Acts of Thomas: Thomas was a disciple of Jesus. but here there is more to the story. Jesus apparently has a twin brother, Thomas, who is one-in-the-same as Thomas the disciple. Thomas is sold into slavery by Jesus to work for the “King of India,” in which Thomas is then enabled to be a great missionary to India, performing many miracles. This book gave rise to the narrative that Thomas founded the Christian community in southern India. Thomas upholds an extreme ethic of asceticism, forbidding sexual relations even among those who are married, and urging against having children. Towards the end of the book, a woman raised from the dead describes some pretty graphic descriptions about the horrors of hell that anticipate what we find in Dante’s Inferno. Most scholars date the Acts of Thomas to the third century.

- The Acts of Peter: The adventures of the Apostle Peter are set in contrast with the movements of Simon Magus, thought to be the first Christian heretic found in the canonical Book of Acts. Peter ultimately defeats Magus, when Peter journeys towards Rome. There in Rome, Peter is finally martyred, being crucified upside down. Part of the Acts of Peter serves as a backdrop narrative for the 1951 film, Quo Vadis (an excellent movie, by the way).

Scholars debate with one another as to how much historical material is actually being described in these books, as they are likely a mix of both fact and fiction. But where to draw the line between the two is difficult to pin down.

The Apocalypse of Peter has been dated back to the 2nd century C.E. Like the Gospel of Peter, it was rejected as apocryphal by the early church, and therefore inappropriate to place into the New Testament. It claims to have been written by Peter himself. Scholars universally recognize this as a classic example of pseudepigrapha (spurious writings). This fragment was discovered in Egypt (credit: Wikipedia)

Lost Letters That Failed the “Sniff” Test for the New Testament

Ehrman’s collection in his Lost Scriptures also includes additional letters attached to well-known persons in our New Testament. Scholars today recognize that these apocryphal letters were indeed of dubious origin.

Take Third Corinthians, for example. Third Corinthians is generally dated to the second century, long after Paul’s death. It was primarily written as a proto-orthodox critique of certain heterodox teachings, such as Gnosticism, which denied the humanity of Jesus and the bodily resurrection of Jesus. Some Christians in the early church accepted Third Corinthians as genuine, such as the Armenian church, but even in the second century others recognized this letter as a forgery, despite its supposed good intentions. In more recent times, some Quakers who came to America during the colonial period had a copy of Third Corinthians with them.7

Ehrman includes other fascinating examples of such supposed lost correspondence, including:

- Correspondence of Paul and Seneca: The likelihood that Paul ever had any contact with the contemporaneous and great Roman philosopher Seneca is extraordinarily slim. Nevertheless, some imaginative pseudepigraphical author drafted a series of letters between the two influential thinkers of the first century.

- Paul’s Letter to the Laodiceans: The canonical New Testament letter to the Colossians mentions a separate letter to the Laodiceans by Paul which is now lost. But this did not prevent someone in the second century from writing a forgery in the name of Paul having the contents of this letter. Ehrman (p. 165) suggests that this may have been written by someone who sought to write a more proto-orthodox version of yet another letter to the Laodiceans found in the first attempt at a collection of New Testament writings, compiled by the notorious second century heretic, Marcion of Sinope.

- The Epistle of Barnabas: Claimed to have been written by a companion of Paul, this “The Letter of Barnabas” is worthy of extended analysis, for perhaps another blog post. But in summary, this epistle enjoyed popularity during the early church era, even among certain historically orthodox believers, some considering it a candidate for the New Testament. But thankfully, it was dropped from consideration for good reason. It takes a very negative view of Judaism, ridiculing the Jews for having taken the teachings of the Law of Moses literally and missing the metaphorical meaning which the author believes that orthodox Christianity understood to be the correct way of interpreting the Old Testament. The letter probably helped to drive a deeper wedge between Jews and Christians, as Christianity made the transition from being primarily a Jewish movement to an almost exclusively Gentile movement.

- Pseudo-Titus: A letter which dates back to about the 5th century, was obviously not written by Titus, though Titus is claimed to be the author. The work takes a very negative view of human sexuality, even calling for celibacy even among married couples, as a higher spiritual calling.

Ehrman includes selections from the Shepherd of Hermas, which like the Epistle of Barnabas, enjoyed great popularity among the early Christians, as some thought it to be fitting for the New Testament canon of Scripture. But aside from certain doubts of authorship, who according to some was supposedly the brother Pius, an early Roman bishop, the book was rejected from the canonical list, partly due to a tendency towards a works-righteousness mentality. The Shepherd of Hermas records a number of visions laden with allegorical messages, and is preoccupied with concerns about falling into sin after conversion. The Christian church is symbolically represented by a lady who often appears in these visions. Readers are told that those Christians who have fallen into such sin will have a second chance to repent, but only that second chance. After that, not even a later repentance of sin will allow for the salvation of the person.8

The Gospel of Mary, a facsimile on display at the Museum of the Bible, in Washington, D.C. The Gospel of Mary is often associated with Gnostic Christian collection of writings, dating back to the 2nd and 3rd centuries of the early Christian movement. The Gospel of Mary is of particular interest to modern feminists, as Mary Magdalene is featured as having received secret knowledge from Jesus.

A Super Gospel?

There was even an attempt to come up with a kind of “super” gospel, which attempted to merge all four of the well-acknowledged gospels into one text, in order to harmonize the differences found in our canonical gospels: Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Simon Gathercole includes an outline of this Diatessaron (not the whole text) in his collection of The Apocryphal Gospels, but introduces it with a quote from Theodoret (393-460 CE), an early church father who was disturbed by how popular this “super” gospel was among some churches, taking drastic action to clean up the mess:

“This Tatian composed a Gospel called the “Diatessaron”, cutting out the genealogies and whatever else shows that the Lord was born, physically speaking, from the line of David. It was not only those of Tatian’s own sect who made use of this Gospel, but also people who otherwise followed the apostolic teachings. They did not recognize the wickedness of the composition but treated it naively as a compendium of the Gospels. I managed to find more than two hundred copies of the book revered in our own churches, so I collected them all and removed them, replacing them with the Gospels of the four evangelists” (Gathercole, p. 71)

You would think that a studied attempt to produce a gospel harmony would have been well-received by church leaders, but apparently not. Presumably, Theodoret judged the Diatessaron to have “the wickedness of … composition” in that Christians had confused it with an original document going back to the apostles themselves. Gathercole dates Tatian’s Diatessaron to the mid to late second century. Part of the problem in reproducing the Diatessaron in its entirety is that there is no early copy of the text which has survived to the modern day, so only an outline of its contents can be reliably reproduced. Furthermore, scholars do not even know what the original language was for the Diatessaron. Gathercole’s outline is from a late Arabic copy (Gathercole, p. 71).

Ehrman’s collection towards the end of his volume includes various works which describe various stages of the development of the Christian canon. One of the first canonical lists in use by the proto-orthodox is the Muratorian Fragment, the oldest surviving list of books to make up our New Testament. The fragment is named after the Italian scholar who discovered the document in the early 18th century. The Muratorian Fragment is dated somewhere in the latter half of the second century.

The Muratorian Fragment lists all of the books of our current New Testament, except for Hebrews, James, 1 and 2 Peter, and 3 John. However, it also includes certain texts not found in our New Testament, like the Shepherd of Hermas and the Apocalypse of Peter, which could be read privately but not read in church. Other texts attributed to Marcion, like the supposed Pauline letters to Laodicea and Alexandria, and various Gnostic teachers are to be rejected completely. The Apocalypse of Peter is of interest in that it describes a journey through heaven and hell, a kind of literature which anticipates Dante’s Divine Comedy. The Apocalypse of Peter assumes a doctrine of eternal torment regarding hell in very vivid imagery, denying both universalism and annihilationism.

Simply reading through some of various texts that were not included in the New Testament does not fully explain the whole process as to why these texts were finally not accepted into the canon of Scripture, a topic for another time. However, it does give you a look into what these texts say, how they substantially differ with the New Testament, in certain cases, while in some sense differing only somewhat in other cases.

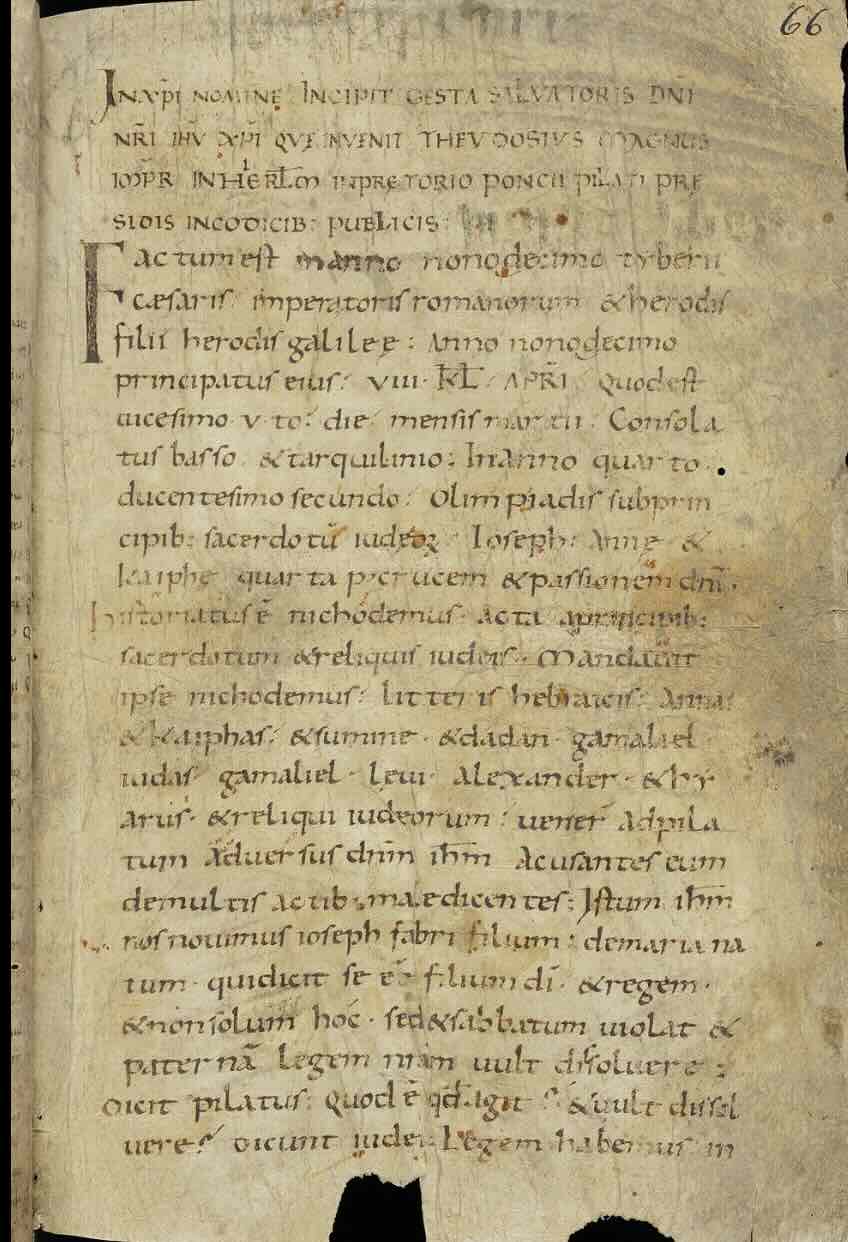

A 9th or 10th century copy of the Gospel of Nicodemus, sometimes called the Acts of Pilate, in Latin.

What To Do With Lost Scriptures and Apocryphal Gospels?

The “lost gospels” and other “New Testament-ish” apocryphal texts covered by Bart Ehrman’s Lost Scriptures and Simon Gathercole’s The Apocryphal Gospels have enjoyed varying degrees of popularity throughout Christian history, among certain communities. But particularly since the Protestant Reformation, these texts were mostly forgotten, except when archaeological discoveries, particularly in the 19th century and the 20th century recovery of the Nag Hammadi Library unearthed these forgotten books. Every few years or so, a new discovery is announced of some “lost scripture,” fodder for a lot of conversation as to why we possess the New Testament canon that we currently have.

Back in the 1990’s, progressive Christian scholar Elaine Pagels published several books, which on a popular level discussed the so-called “Gnostic Gospels,” rediscovered in 1945 in Egypt in the Nag Hammadi library. I read those books with great interest as Pagels uncovered a look at Christianity which I never heard about in my evangelical church circles. I must admit that learning about these books helps to explain why some Christians over the centuries have sought to find answers to questions that the New Testament does not fully address. But make no mistake about it, Gnostic Christianity bears very little resemblance to historic orthodox Christian faith.

Many Christians are completely unaware of the existence of such apocryphal texts, whereas certain skeptics of Christianity look upon the designation of such texts as “apocryphal,” or even certain ones as “heretical,” as examples of the institutional Christian church supposedly hiding “the truth” from people, as a means of maintaining a grip and control on the minds of Christians and preserving power and privilege. Such a mindset takes on the character of either cynicism or even a kind of spiritual elitism, which suggests that the reader of these apocryphal texts can gain some kind of “inside scoop” that other, more historically orthodox Christians fail to possess.

The more traditional view, one that I accept, is less cynical and does not rely on the logic of conspiracies. Instead, there were always a few loose cannons in the early Christian movement who gave themselves over to quirky, at best, or downright distorting versions of the story of Jesus and the rest of the New Testament. Some of these texts would best be characterized as “fan fiction,” while others were polemical in nature. Some were motivated by good intentions, while others were motivated by the idea of inventing their own version of Christianity to suit some agenda at odds with the genuine narrative handed down from the original apostolic followers of Jesus.9

One thing is certain in that by the second century, there was a lot of diversity within the Christian movement, which led to efforts by historically orthodox Christians to push back against alternative voices. Ironically, many of the same alternative voices have managed to make a comeback in our own day, in the 21st century.

While Bart Ehrman’s Lost Scriptures contains more apocryphal material, and is therefore, more complete, Simon Gathercole’s The Apocryphal Gospels, while including certain texts which Ehrman omits, is on the whole a slightly more suitable collection, if you could only pick one of the two books. Largely this is the case as Gathercole’s evangelical commitments poke through enough in his introductions to the texts, without being overly dismissive of skeptical viewpoints. Ehrman’s work, on the other hand, is comparably more skeptical, but thankfully without being overly dismissive of historically orthodox viewpoints. Both works overlap with shared material, but both emphasize different aspects of apocryphal New Testament era works. In fairness, I have not read all the way through Gathercole’s book, but I have read enough to get the sense of how he approaches the apocryphal texts he is studying. Nevertheless, both Ehrman’s Lost Scriptures: Books that Did Not Make It Into the New Testament and Gathercole’s The Apocryphal Gospels (Penguin Classics) are important contributions to the scholarship of early Christianity and are worthy of study.10

We should be thankful that Jesus made his incarnate appearance in human history 2,000 years ago and not today in our social media age with its proliferation of “fake news” and the “like” button. Since the 19th century, scholars have been able to unearth a number of these lost texts. The situation of the early church was not as confused and contrived as Dan Brown’s popular The DaVinci Code portrays it. However, the story is complex enough. The history does show the need for a type of vetting process that the early church deployed to try to weed out both well-meaning yet sincerely misguided texts, along with deliberate misrepresentations of the early apostolic record, while preserving what was good and true.

It is important recognize that the development of the New Testament canon was an organic process. There were no set of meetings where bishops took any votes on which books were “in” and which books were “out.” Instead, there was a sense developed over many decades that these 27 books we have in our New Testament had the ring of truth in them.

It makes one appreciate the fact that we have had thoughtful and influential early church fathers who sought to keep the Christian movement on track. While the study of such apocryphal texts can help give us a fuller understanding of what early Christianity looked like, one must be careful not to immediately come to cynical conclusions which impute bad motives on behalf of historic orthodox Christianity. Instead, it is worth considering a better alternative; that is, that the early church in its historically orthodox form got the essential story of Christianity right to begin with.

Simon J. Gathercole. United Kingdom New Testament scholar, Professor of New Testament and Early Christianity, and Director of Studies at Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge. I met Dr. Gathercole on a visit to Cambridge, at his church, in January, 2024.

For a very good lecture which covers the topic of “apocryphal gospels,” which cites Gathercole’s book, which explains the differences between the “apocryphal gospels” and what we have in the New Testament, I would recommend the following from Dr. Peter Gurry. Dr. Gurry has co-written with John D. Meade Scribes and Scriptures: The Amazing Story of How We Got the Bible, which is on my reading list, and covers much of what he discusses in this lecture. Enjoy!!

Notes:

1. Dan Brown’s blockbuster 2004 novel, The DaVinci Code, popularized the idea that there were “lost gospels” which the Christian church across the centuries wrongly suppressed. The misinformation that Dan Brown and others spread twenty years ago has led to a renewed interest in learning about various New Testament apocryphal gospels and other controversial writings. However, scholars have known about such apocryphal works for decades, if not centuries. The problem is that many of these apocryphal works have been lost, and we only possess fragments of them, preserved by heresiologists like Irenaeus. Nevertheless, recent discoveries, like the Gospel of Judas, continue to perk interest into the question of how the New Testament canon was formed. Baylor University historian Philip Jenkins has written about these so-called “lost gospels.” The bottom line is that such “lost gospels” are generally dated too late to be considered for serious inclusion into the Christian New Testament canon. Jenkins has written several other articles of interest on the topic of “lost gospels,” and other “lost scriptures.” Here is a late August, 2025 installment of Philip Jenkins’ series on this topic. Another installment in early September.↩

2. One more word about comparing Ehrman’s Lost Scriptures to Gathercole’s The Apocryphal Gospels. Ehrman is a skeptic and not a Christian, whereas Gathercole is an evangelical Christian. Both are world-class scholars. Nevertheless, cognitive bias is something that no scholar can completely avoid. Yet in these two volumes both scholars are relatively restrained in keeping their biases in check. The focus of these two volumes is primarily on offering accurate translations of these apocryphal texts, and comparatively, the translations offered by Ehrman and Gathercole are remarkably close. Because I spent more time reading through Ehrman’s work, most of this review will focus on Ehrman’s Lost Scriptures↩

3. Frankly, the most bizarre and disturbing apocryphal gospel described between Ehrman’s and Gathercole’s book is the Greater Questions of Mary, found in Gathercole’s collection (p. 176-177). While we have no surviving copy to the Greater Questions of Mary, the early church father Epiphanius of Salamis (about 310/320 – 403 CE) describes the work, in Gathercole’s words with: “Here Jesus is said to have revealed to Mary the obscene rituals which Epiphanius’ pornographic account has attributed to the Gnostics, rituals which Jesus himself allegedly initiated. This is perhaps the most surprising of all apocryphal Gospel fragments.” I am less inclined to quote the text from Epiphanius as the obscenity is very, very disturbing.↩

4. Dallas Seminary evangelical Bible scholar, Daniel Wallace, has stated that the story of the woman caught in adultery was his favorite story of Jesus not found in the Bible. The story of this interesting portion still found in most printed Bibles today is worthy of a separate blog post, which I hope to get to in the future.↩

5. Some do wonder why Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist, if indeed Jesus was sinless. But if we carefully think through the doctrine of the Incarnation, a good answer can be be given to this question: For if indeed Jesus took our sin upon himself, not simply through his death on the cross, but also by the very fact of becoming God incarnate, the act of baptism by Jesus enacts for us the washing away of sins on our behalf. Jesus does not need to undergo baptism for any supposed sin on his part, but he does undergo baptism for the sake of our sins. 2 Corinthians 5:21 puts it well: “ For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God.” I would recommend Thomas F. Torrance’s The Meditation of Christ, which looks at how the incarnation of God in Christ is intrinsically related to the doctrine of the atonement culminating with the death of Jesus on the cross. Red Pen Logic offers a different explanation for addressing the question about Jesus’ baptism. However, an even better answer draws on a studied understanding of Leviticus (see the three part Veracity blog post series). The “sin offering” instructions found in Leviticus 4 are not exactly clear in terms of application. Some scholars suggest that the translation of “sin offering” is actually misleading, and that it should be a “decontamination offering” instead. This would include both an offering for “unintentional sin” as most Christians generally understand it. However, it would also include an offering related to “ritual impurity,” a condition where someone was designated as unclean, but that there was no “sin” involved. In the Leviticus, ritual impurity, which is not sinful, is different from moral impurity, which is sinful. It is possible that there are cases where a “sin offering” would be appropriate to deal with ritual impurity, which is not sinful, such as when a woman gives birth to a child, she is designated as ritual impure for a period time, where a “sin offering” is required, though clearly giving birth to a child is not sinful (see Leviticus 12:1-8). It might be that Jesus underwent baptism as a purification rite, which was not due to sin, but rather to ritual impurity. Since ritual impurity is not sinful, there is no conflict with becoming ritually impure and the concept of a sinless savior. ↩

6. My visit last year to the Museum of the Bible included a chance to look at a facsimile of the Gospel of Mary on display.↩

7. See Veracity blog post series on Matthew Thiessen’s A Jewish Paul. Thiessen argues that many second century Christians came to accept the idea that Paul believed in the “resurrection of the flesh,” which was in contrast with Paul’s genuine thought that “flesh and blood” can not inherit the Kingdom of God, see 1 Corinthians 15:50. Paul believed that the resurrected body for believers would not be corruptible, as opposed to our current, fleshly bodies, which are indeed corruptible and susceptible to decay and death. It would be more accurate to say that our current fleshly bodies will be transformed in the general resurrection to become “spiritual bodies,” as described by Paul in 1 Corinthians 15. I argue that the pseudonymous author of Third Corinthians never fully grasped that nuanced distinction. Whether or not early Christians who ultimately read and dismissed Third Corinthians as a forgery picked up on that problem is unclear.↩

8. See evangelical New Testament scholar Craig Keener video on the Shepherd of Hermas. Also, see this interview with Dallas Seminary professor Michael Svigel on the Shepherd of Hermas. For a progressive Mormon and scholarly approach to the Shepherd of Hermas, see this lecture by Centre Place. ↩

9. A common narrative to critical scholarship suggests that what is often characterized as “historic orthodox” Christianity, which traces itself back to the Apostle Paul and forward from there to the Council of Nicaea, which gives us the Nicene Creed, the great ecumenical creed adopted by Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and most Protestant churches, was simply one tradition among several which vied for control of early Christian movement. Other traditions, such as Gnosticism, Ebionitism (of which there are several varieties), Marcionism, and Arianism, competed with the “proto-orthodox” tradition, and the “proto-orthodox” party eventually won the debate, giving us our 27 books of the New Testament. This narrative is associated with the Walter Bauer thesis, a popular conceptional paradigm sees the development of “heresy” as a means by which proto-orthodox and later orthodox Christians sought to silence and marginalize competing voices. The well-known critical scholar, Bart Ehrman, is a strong advocate of the Bauer thesis.↩

10. Bart Ehrman has a companion book to Lost Scriptures, aptly titled Lost Christianities, which from my understanding from various reviews has a somewhat more polemical tone, where he analyzes these “lost scriptures” to suggest that early Christianity, even into the first century, was inherently diverse, a theme articulated by the early 20th century German scholar, Walter Bauer. Alternatively, a more historically orthodox approach challenges the Bauer thesis, suggesting that aside from the conflict between Jewish and Gentile Christians, there was less theological controversy in the first century of the Christian movement. ↩

February 14th, 2026 at 9:06 pm

According to Eastern Orthodox scholar Father Stephen De Young, the “Wisdom of Solomon” was listed as part of the Muratorian Fragment (Muratorian Canon), as it was written in Greek (not a translation) in the 1st century, during the early Christian era by a Jewish author, so it was considered as a part of the New Testament by early Christians, though it did not make the final “cut” into the canon in the 4th century:

LikeLike