As a female author and speaker, Elisabeth Elliot stands as one of the most well-known and influential evangelical women in the 20th century. It was after her service for a little over a decade in Ecuador when Elisabeth Elliot returned to the United States in 1963, to her family home in New England, to pursue her work as an author and missionary speaker.

Before her permanent move back to the United States, Elisabeth Elliot had written three books, the first about the five missionaries killed by the Waorani, Through Gates of Splendor, then her biography of her late husband, Jim Elliot, Shadow of the Almighty: The Life and Testament of Jim Elliot, and finally a follow-up book about her missionary work with the Waorani, The Savage, My Kinsman.

Upon returning to New England, she wrote her first and only novel, No Graven Image, and a biography about Kenneth Strachan, the founder of the Latin American Mission, titled Who Shall Ascend: The Life of R. Kenneth Strachan of Costa Rica. Her 1968 book about her ten weeks in Israel right after the Six-Days War, Furnace of the Lord, sparked controversy, but as she would put it, she was only concerned about “telling the truth,” and letting consequences follow. She would eventually write several other books on various topics, and even becoming a contributor to the New International Version Bible translation project.

Her speaking career gave her opportunities to travel widely, appearing before church gatherings, college student meetings, and other settings where she was asked often to talk about her life as a missionary in Ecuador. Elisabeth Elliot could be quite harsh in her criticism of certain practices by some evangelical missionary agencies, such as the tendency to inflate the number of converts in distant lands in order to raise more money. On more than one occasion, she had conflict sharing the stage with insecure men, who were bothered with the idea of sharing a speaking platform with a woman. Nevertheless, her speaking engagements became a significant component for much of the rest of her life.

But perhaps the most important event in her life during this period was her marriage to a college and seminary professor, Addison Leitch, the focus of this second of a three part series reviewing her life through the lens of her biographers, primarily Lucy Austen and secondarily Ellen Vaughn.

Being Elisabeth Elliot, is the second volume of a two-book biography on the life of Elisabeth Elliot, by Ellen Vaughn. Ellen Vaughn serves on the board for International Cooperating Ministries, founded mainly by Dois Rosser, inspired by his well-loved Bible teacher, Dick Woodward. Vaughn also wrote the book Jesus Revolution, along with Greg Laurie, which became a popular movie in 2023

Prelude to Elisabeth’s Second Marriage With Addison Leitch

Following the story laid out initially in the first blog post in this series, the perpetual rift between the two missionaries in Ecuador, Elisabeth Elliot and Rachel Saint, had forced Elisabeth to leave Ecuador and return permanently to the United States in 1963. Though discouraging Elisabeth in a devastating way, she also saw her return to the United States as an opportunity to pursue a career as an author, as biographer Lucy Austen notes in her Elisabeth Elliot, A Life.

Elisabeth wrote for numerous publications, such as Eternity, a Christian magazine popular in the mid-20th century.. As an author, Elisabeth was frustrated with much of what she saw in her evangelical subculture, a sense of angst which came out in her writings. As a biographer, Elisabeth’s Who Shall Ascend: The Life of R. Kenneth Strachan of Costa Rica described a great missionary hero, who advocated missionary strategies ahead of his time, yet who died an early death with a lot of unanswered questions about his life. It took eleven years for Elisabeth to write this book, which is currently out of print.

A quote from the book, as noted by reviewer Trevin Wax, can also adequately describe Elisabeth Elliot herself:

“God alone can answer the question, Who was he? . . . The answer is beyond us. Here are the data we can deal with. There is much more that we do not know—some of it has been forgotten, some of it hidden, some of it lost—but we look at what we know. We grant that it is not a neat and satisfying picture—there are ironies, contradictions, inconsistencies, imponderables. . . . Will Kenneth Strachan have been welcomed home with a “Well done, good and faithful servant,” or will he simply have been welcomed home? The son who delights the father is not first commended for what he has done. He is loved, and Kenneth Strachan was sure of this one thing.”1

Elisabeth Elliot was focused on her speaking and writing career, while also being a single parent to daughter Valerie. Before her second marriage, to an Addison Leitch, whom she had not met yet, Elisabeth focused on friendships and time with family, though she and her mother, Katherine, would run into conflict with one another on more that one occasion. Apparently, both Elisabeth and Katherine were strong-willed women.

A Close Friendship: Eleanor Vandervort

Elisabeth was also deepening a friendship with a fellow Wheaton College alum, Eleanor Vandervort. Like Elisabeth Elliot, Eleanor Vandervort in college desired to become a missionary and do Bible translation work. Vandervort lived among the Nuer tribe in Sudan for 13 years, translated several books of the Bible into the Nuer native language. Political unrest in Sudan forced Vandervort to return to America.2

Much like Elisabeth, Vandervort aspired to be a writer as well, writing a book about the Nuer tribe, A Leopard Tamed. Upon moving to Massachusetts, Elisabeth Elliot and Eleanor Vandervort shared a lot of their lives together. The former missionary to Sudan would often care for Elisabeth’s daughter Valerie, when the former missionary to Ecuador would travel somewhere for various speaking engagements.

Elisabeth had designed and oversaw the building of her own house. By 1968, it would appear that Elisabeth had grown accustomed to living the life of being a single mother, while working as a writer and speaker. But then, along came a college professor, Addision Leitch.3

A College Professor In Transition Catches Elisabeth Elliot’s Eye

They met at one of Elisabeth’s speaking engagements.

Addison Leitch had been previously married to Margaret Heslip. But Margaret died of cancer, and Addison was getting to know Elisabeth Elliot while Margaret was getting sick. Growing up as a Presbyterian, Addison Leitch had a different background than the less denominationally-committed Elisabeth. But Elisabeth believed that Addison Leitch had the qualities in him that she lacked in herself. For one thing, Addison Leitch was determined in his pursuit of Elisabeth, and so the two were married less than six months after Margaret’s death.

Lucy Austen believes that Addison Leitch violated his marriage vows to his first wife by inappropriately pursuing a relationship with Elisabeth, while his wife Margaret was dying of cancer. This is a tough call to make. I asked my wife about this, and she suggested that it is quite possible that Margaret might have encouraged Addison towards such an end. Perhaps Margaret suggested to Addison that he pursue cultivating a relationship for a second wife as soon as possible, out of love for him and wanting what was best for him, knowing that her own death was near. Would such a possibility adequately explain the morality of Addison’s behavior? Food for thought!!4

After Jim Elliot’s death, Elisabeth had no intention of remarrying. But she was eventually won over to Leitch’s advances, and greatly influenced by him. Elisabeth gained a better appreciation for older theological traditions, different from her brand of evangelicalism. Whereas she once elevated love as possibly the only absolute for a Christian, she began to argue for other absolutes for the Christian, a belief shared by Leitch. She began to share in Leitch’s Christianized neo-Platonism, a belief that the visible world is yet an imperfect shadow of the invisible perfect world (Austen, chapter 29).

Over the years, she became more open to beliefs and practices which would have been frowned upon in her very conservative evangelical youth. She became more open to certain aspects of Roman Catholicism, particularly after her brother Thomas converted to Catholicism in 1985, which led to him resign from his teaching position at the stalwart Protestant evangelical Gordon College. She was open to the moderate use of alcohol, as long as it did not lead to drunkeness. Yet knowing that alcohol use was controversial, she refrained from telling her readers about her more moderate views.

Discerning God’s Will?

According to Lucy Austen, Elisabeth Elliot began to rethink the spirituality of her evangelical youth, which had an intense and even burdensome focus on individual performance, a continual re-examination of the self, in hopes of seeking after God’s perfect will. As another book reviewer put it, Trevin Wax at the Gospel Coalition:

“She [had been] given over to excessive self-examination, driven by a desire to ensure every moment of every day was devoted to obedience. Her letters betray an obsession with heeding God’s guidance, deathly afraid she might step outside of his will in some way. It’s almost as if she thought God had placed her blindfolded in a field, only then to whisper to her faintly about where she should go.”

This method of individual spiritual discernment she grew up with was no longer working for her. Instead, she began to find solace in the ancient liturgy of the church, with its focus on worship and community. Reciting prayers and texts like the ancient creeds of the church began to free her from her self-obsession with continual self-introspection. She joined the Episcopal Church (Austen, chapter 29).

Moreover, perhaps knowing God’s will was not always about finding God’s singular, perfect will, as her Keswick Holiness tradition taught her, but rather that a person might have several choices available to that person, and that God might be pleased with either one of those choices. In an American evangelicalism which often focused on finding that one path for knowing “God’s will” before setting out on a journey, Elisabeth’s questions challenged the spirituality status quo.

This rethinking about discerning God’s will became a recurring theme in Elisabeth’s letters, even from her later days in Ecuador, on up through the writing of her books decades later. She came to reject the school of thought that taught that one must come to the point of having no will of one’s own before one can know the will of God. Instead, she recognized that Jesus had his own will, in that Jesus himself prayed, “Not my will, but thy will,” speaking of the will of the Father (Luke 22:42). She was learning to see that she still had a will of her own, but that she should learn to trust that God knows what he is doing (Austen, chapter 23).

Elisabeth would often look back at her time in Ecuador, using an analogy of following a guide through the forests of Ecuador, for learning about the will of God. Instead of being in a position of not moving, waiting for God to move her, she set off moving in a particular direction trusting that God would redirect her when necessary. Not knowing the way herself, she had to trust that the guide, who was always with her, was leading her in the right way, even if she had very little idea where she was going at any moment in time. The same could be said about following God, the one true guide in life (Austen, chapter 30).

Elisabeth Elliot had eventually developed a three-fold test for discerning God’s will when decisions had to be made. She considered:

- (1) the circumstances,

- (2) the witness of the Word,

- (3) peace of mind.

This revised method would become crucial in her next stage of life to come. (Austen, chapter 31)

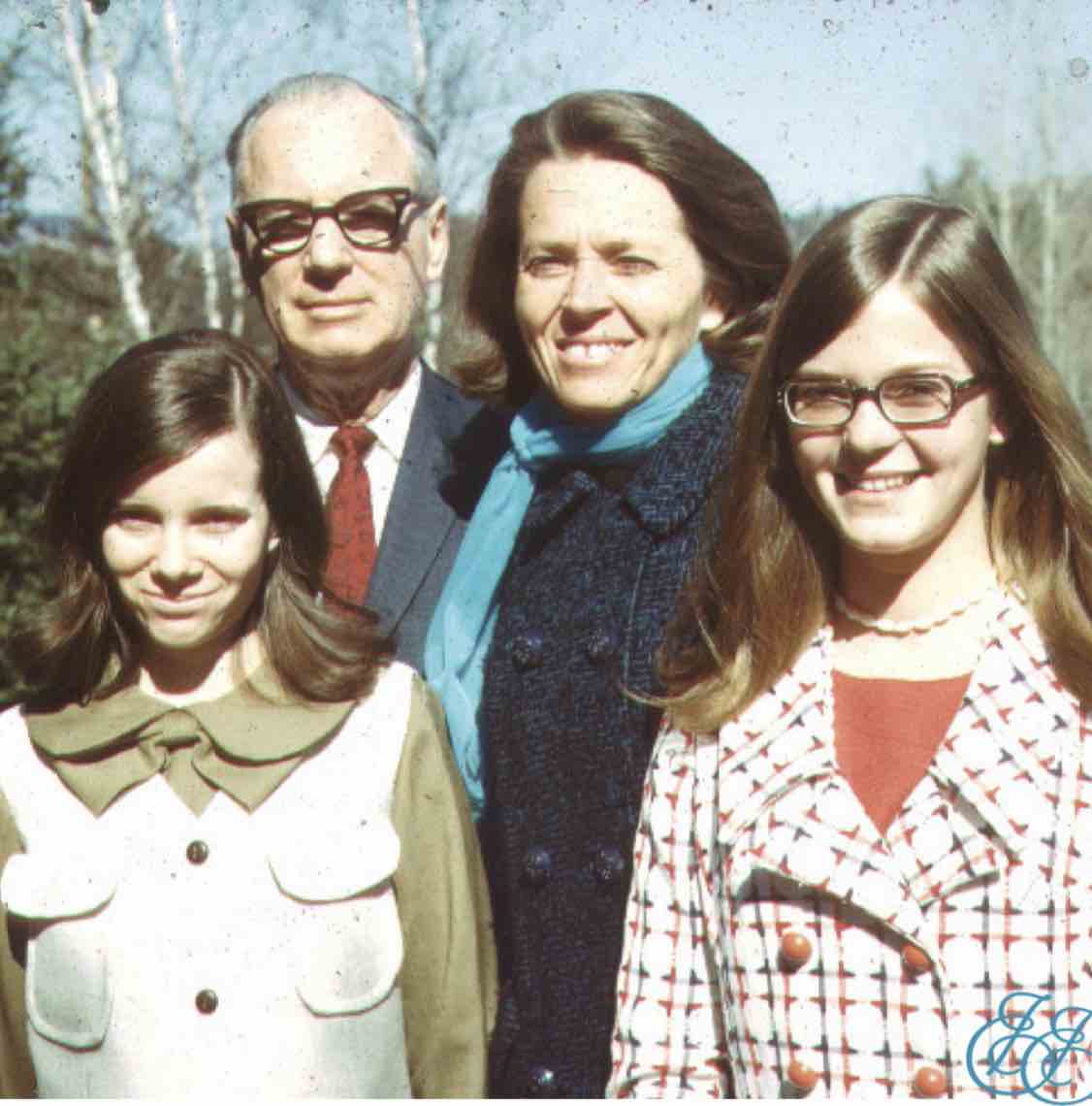

Elisabeth’s marriage to Addison Leitch was filled with much joy in the early years of the marriage. He integrated well within the family, becoming a father figure to Elisabeth’s daughter Valerie, who by then was now a teenager.5

Addison Leith and Elisabeth Elliot, along with Valerie Elliot, and Addison Leitch’s daughter, Katherine Leitch.

Cancer Diagnosis, Suffering, and Death of Her Second Husband

Biographer Ellen Vaughn notes from Elisabeth’s journals that Elisabeth felt more in love with Addison Leitch than she did with her first husband, Jim. Sadly, the moments of joy Elisabeth experienced were eventually marked by a deep period of suffering.

About the third year into her marriage with Addison Leitch, Leitch was diagnosed with cancer. The cancer treatments Addison Leitch went through were very painful and difficult, and they changed his personality, making him more irritable at times. Elisabeth sought changes in diet, following the then popular teachings of nutritionist Adelle Davis, in hopes that her husband would survive this debilitating disease. She experienced frustration, praying fervently for her husband’s healing, but was always desiring to follow and accept God’s will no matter the cost. Elisabeth cared for Leitch for a year until he died in 1973. Now, at mid-life, Elisabeth Elliot had survived two husbands.6

But the story of Elisabeth’s married life, and her life in general, was far from over. After Addison Leitch’s death, Elisabeth took on two male boarders from the nearby seminary, Gordon-Conwell. The younger one ended up marrying Elisabeth’s daughter, Valerie. The older one, Lars Gren, ended up marrying Elisabeth, four years after Leitch’s death. In the next and final blog post in this book review series, Elisabeth’s marriage to Lars Gren takes center stage.

It was at this last part of Elisabeth Elliot’s life that has for many become the most controversial part of her legacy. Stay tuned.

Link to the third and last post in this series.

Notes:

1. Ellen Vaughn’s biography, Being Elisabeth Elliot, the second volume in a two part series, details more about Elisabeth Elliot’s frustrations and challenges in being an author, suffering through writer’s block many times and having certain short pieces rejected by publishers. Elisabeth had struck up a strong friendship with LIFE magazine photographer Cornell Capa, who first came to Ecuador in 1956 to cover the story of the murdered missionaries with his camera. She and Capa held many intellectual interests, and they had many deep spiritual conversations, despite the fact that Capa considered himself to be an agnostic/atheist. Capa proved to be an invaluable encouragement in her work as an author. Capa also propositioned her to have sexual relations with him. Elisabeth, following her Christian convictions, turned him down.↩

2. Ellen Vaughn’s biography of Elisabeth Elliot, Becoming Elisabeth Elliot, the first volume, goes into more detail about Eleanor Vandervort. When Elisabeth decided to leave the Waorani mission work, she was not immediately convinced of moving back to the United States. Elisabeth and daughter Valerie stayed in Ecuador, as Elisabeth took some time to consider other avenues of ministry in the country, perhaps translating the Bible into other native Ecuadorian languages. But it was a visit from Vandervort which prompted the move back to the United States, as Elisabeth viewed her longtime college friend and fellow missionary as a kindred soul, who understood her. Vandervort had left Sudan when the Islamic movement had seized control of the government, and decided to replace Roman script in public education with Arabic script. Since Vanderovrt’s translation work was in Roman script, she feared that much of her work might be sidelined by the Islamicist efforts to promote Islam in Sudan. When the government finally forced Vandervort out of the country, she longed to meet back up with Elisabeth Elliot, and then the two single missionary women decided together to return to the United States and pursue new vocational paths.↩

3. Ellen Vaughn in Being Elisabeth Elliot reports that even though Vandervort, usually known as “Van,” originally hit it off well with Elisabeth, Van did not enjoy the kind of success that Elisabeth had with her writing career, causing some tension after a while in their relationship. Van was evidently also off-put by Elisabeth’s decision to marry Addison Leitch, as Van could then no longer live with Elisabeth. The two remained friends, but Elisabeth’s marriage changed the character of the relationship between the two women.↩

4. Ellen Vaughn’s report about Addison’ pursuit after Elisabeth, in Being Elisabeth Elliot, comes across as a tad bit creepy. Evidently however, Elisabeth was still smitten by the college professor. You would have to read Vaughn’s book yourself to grasp what is meant by all of that. Nevertheless, Vaughn reports that Elisabeth was comparatively more in love in Addison Leitch than she was with Jim Elliot.↩

5. Ellen Vaughn retells an interesting anecdote about Addison’s interaction with young Valerie. Valerie had asked this seminary professor and step-father about the doctrine of predestination. Addison responded by saying that predestination is about the mystery and grandeur of God. One day the believer will proceed to enter through the gates of heaven, because of the blood of Jesus Christ. The front of the gate is engraved with the words “Whosoever will, let him come,” from Revelation 22:17. Upon passing through the gate, the believer will look back at the inside of the gate that reads: “Chosen in Christ before the foundation of the world,” from Ephesians 1:4. God calls everyone to follow Christ, freely, and God calls people to himself, and both truths are both 100% true. Valerie appreciated the profound wisdom her step-father gave her.↩

6. In her second book on Elisabeth Elliot, Ellen Vaughn goes into greater detail about the nearly year-long decline of Addison’s last battle with cancer. Addison Leitch had grown increasingly despondent and depressed about his condition, and the physical stresses put many demands on Elisabeth Elliot, caring for her dying husband. Hospice care would not be introduced to the United States until a year after Addison Leitch’s death, so Elisabeth had to bear most of the brunt of caring for her husband. One extraordinary feature of Being Elisabeth Elliot is the author’s own story of her dealing with the battle of cancer of her husband. Ellen Vaughn’s husband also died of cancer, running roughly parallel to the period she was working through Elisabeth’s journals regarding Addison Leitch’s cancer..↩

What do you think?