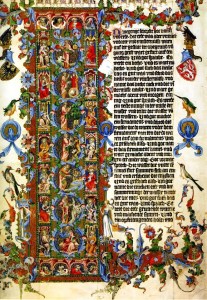

If you want to understand the controversy over indulgences and purgatory, that sparked the Reformation 500 years ago, you need to understand something of the theology of a “treasury of merit,” in Roman Catholic theology.

For Western medieval Christians (and as officially found in the papal teaching of Rome today), those who die and go to purgatory, must go through a type of purification, before they can fully enter God’s presence in heaven. Medieval Europeans knew that they would endure temporal punishments in purgatory. Indulgences are then God’s provision for offsetting, at least partially, those punishments resulting from sins committed in this earthly life. God has granted the Church, through the power given by Christ to bind and loosen, to intervene and come to the aid of soul in purgatory, with indulgences.

But how is that actually accomplished?

First, we must consider that everyone, believer or non-believer, will be judged by their works. “For we must all appear before the judgment seat of Christ, so that each one may receive what is due for what he has done in the body, whether good or evil” (2 Corinthians 5:10 ESV).

Secondly, Jesus Christ saves a person on the basis of Christ’s works, that make a satisfaction for sin. We can not save ourselves by our own works. Only Christ can relieve us from the eternal punishment due to sin (Hebrews 9:11-18). Therefore, all good works performed by anyone in this life essentially derive their source from Christ Himself. What then becomes of those works, unacceptable to God, that come under God’s judgment? Purgatory provides the answer. Purgatory is the means by which those works, that are not good, are “purged,” from the soul of the Christian.

Thirdly, there are some Christians who have performed an abundance of good works in this earthly life. They store up “treasures” for themselves in heaven (Matthew 6:20). This becomes the basis for the “treasury of merit,” a great supply of good works, resulting from the combined meritorious works Christ and the saints of the church, like the Virgin Mary.

Fourthly, all believers are bound together in this “communion of saints,” those currently alive and those who have already died, where fellow believers can share together and support one another (John 1:12-13). One way of sharing and supporting is through this “treasury of merit,” that can be applied towards lessening the temporal punishments of purgatory. The Catholic Catechism explains the “treasury of merit” this way:

- We also call these spiritual goods of the communion of saints the Church’s treasury, which is “not the sum total of the material goods which have accumulated during the course of the centuries. On the contrary the ‘treasury of the Church’ is the infinite value, which can never be exhausted, which Christ’s merits have before God. They were offered so that the whole of mankind could be set free from sin and attain communion with the Father. In Christ, the Redeemer himself, the satisfactions and merits of his Redemption exist and find their efficacy. This treasury includes as well the prayers and good works of the Blessed Virgin Mary. They are truly immense, unfathomable, and even pristine in their value before God. In the treasury, too, are the prayers and good works of all the saints, all those who have followed in the footsteps of Christ the Lord and by his grace have made their lives holy and carried out the mission in the unity of the Mystical Body. (CCC 1476-1477)

Fifthly, the Church has been granted the power to bind and loosen, since the keys of the Kingdom were granted to Peter by Christ (Matthew 16:19). The theology of indulgences allows the Church to be the vehicle, or means, to apply the treasury of merit, through the prayers of fellow believers, to bring relief towards those who are enduring the pains of purgatory.

This theology of indulgences and purgatory took centuries in the Christian West to develop. By the 16th century, theologians of the Reformation, such as Martin Luther, countered that it is the merits of Christ, and Christ alone, who provides satisfaction for sins, and the punishments resulting from those sins. At first, Luther did not object to the doctrinal formulation of purgatory. He only criticized the abuses of the system, such as the sale of indulgences. But it was not too long before Luther identified the theological doctrine itself as being the root of the problem. For if believers are justified by faith, and faith alone, it renders the whole system of indulgences and purgatory, along with the associated “treasury of merit”, rather superfluous and unnecessary (Ephesians 2:8-9).

A Difficult Text… Colossians 1:24

One of the pivotal proof-texts in this discussion between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism, where the Roman doctrine of the “treasure of merit” is said to have some Scriptural traction, is found here:1

- Now I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I am filling up what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the church” (Colossians 1:24 ESV)

Now all Christians contend that the merits of Christ alone are sufficient for salvation. Nothing else is required. Texts like John 19:30, where Jesus says, “It is finished,” stress this truth.

However, this is not the end of the story, in Roman Catholicism, as Colossians 1:24 is where the abundance of the “treasury of merit” finds an application. Through their sufferings, the sacrificial merits of all followers of Christ, those in this life and the departed, are also somehow2 joined together in building up the Church’s great “treasury of merit,” to provide aid to other believers, thus making up for what is “lacking” in “Christ’s afflictions.” This type of aid becomes the basis for how indulgences are applied to assist souls in purgatory, for the “sake of his body, that is, the church.”

Understood this way, Paul’s text in Colossians may sound like a contradiction to the New Testament teaching about the full sufficiency of Christ’s work on the Cross. Yet Roman Catholic teaching insists that Christ’s work at Calvary is indeed sufficient to save the believer. The “treasury of merit” is therefore different, where Christ continues to work through His church, to complete the work of sanctification (see these earlier Veracity posts, here and here, for more background).

Protestant interpreters balk at this argument. They are quick to point out that the Greek term translated as “afflictions” in Colossians 1:24, is never used elsewhere in the New Testament to describe Christ’s redemptive work at Calvary. Protestants critics also say that it is quite a stretch of Paul’s text to apply this to indulgences and purgatory.

However, the Protestant view leaves us still wondering what to make of Paul’s statement. So then, what is Paul going after in this verse?

Several viable proposals have been made to understand this verse, that pastor and theologian Sam Storms has ably summarized. I will just discuss the most prevailing view here: Many scholars suggest a slightly modified translation of this verse. Instead of “filling up what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions“, it could be better rendered as “filling up what is lacking with regard to the Messiah’s woes.”

An appeal to the larger Scriptural context explains this: In Old Testament thought, there is the theme of the “messianic woes,” of a period of suffering for the Messiah’s people, that precedes the resurrection of the dead and the consummation of God’s Kingdom (see Daniel 12:1-3 and Ezekiel 38). These are not the sufferings that the Messiah himself would experience. But rather, they are the afflictions out of which the messianic age would come. Paul might be thinking of his sufferings to be part of those “messianic woes,” which might also imply that Christians down through ages will also suffer, as a prophetic fulfillment of God’s purposes.

In other words, the sufferings that Paul speaks of here have nothing to do with salvation, and even less with building up a supply in the Church’s “treasury of merit.” Instead, this suggests that Christians, like Paul, will experience suffering, as this is an expected outcome of what happens when the Kingdom of God advances in this world. When people are transformed by the Gospel, the powers of the Devil and world do not like it, and God’s people will suffer accordingly. This fulfillment of biblical prophecy indicates that there is a “filling up,” or completing, of that which is “lacking” in Christ’s “afflictions.”

In this manner, God’s people, through their suffering, participate in the sufferings of Christ. Jesus told his immediate disciples that they will face trials and tribulations. So, when we experience them ourselves, it should not surprise us. Paul’s sufferings therefore benefit other believers, down through the ages, reminding us that we are not alone in our sufferings for the sake of the Gospel, as we await the coming of Christ’s Kingdom.

Admittedly, Colossians 1:24 is a difficult verse. The explanation given above, that ties Christ’s afflictions to the messianic woes, as prophesied in the Old Testament, seems the most plausible.3 Nevertheless, this brief discussion gives us a good idea as to how ideas in Roman Catholic thought, have taken a tricky verse like this, to build into it a theology of indulgences and purgatory, that owes a lot to a long development of church tradition.

Notes:

1. For a good explanation of the treasury of merit, that I used for researching this post, that lays out the doctrine nearly like I have done, but in more detail, see this website, Called to Communion. Called to Communion is put together by Roman Catholics, who are trying to explain the faith of Rome to Protestants. For some helpful discussions about how to understand Colossians 1:24, aside from Sam Storms fine article, include a sermon by John Piper, a brief commentary from Ligonier ministries, and a First Things article by Peter Leithart.↩

2. This is a very confusing point for me; hence, my italicized somehow. I have heard Roman Catholic explanations that the sacrifice of Christ at Calvary is sufficient to deal with sin. But then I have also heard Roman Catholic explanations that suggest that this finished work of Christ also (somehow??) finds application through the church, specifically through the administration of the sacraments, such as through the treasury of merit, based on the abundance of good works performed by the saints. Protestants fully affirm the first point, but they do not buy into the second point. Perhaps I am not getting it, but the whole Roman Catholic theology of merit seems incoherent, at this juncture, and so remains beyond my mental grasp. That being said, Colossians 1:24 is indeed a difficult verse, so it makes sense how the tradition of the treasury of merit does, in a way, explain Paul here, even if it is not ultimately persuasive. ↩

3. The case for the “messianic woes” in interpreting Colossians 1:24 is speculative to some degree, but it is perfectly in keeping with Paul’s Jewish context. Southern Baptist theologian Jim Hamilton has a helpful list of biblical passages that describe the “messianic woes,” available in PDF form. A rather technical article by Andrew Perriman, in PDF format, referenced by Peter Leithart, in footnote #1 above, disputes the “messianic woes” interpretation. I must confess that Perriman goes over my head sometimes, so it is difficult for me to evaluate his argument. But the point is this: The verdict on coming to “the” proper interpretation of Colossians 1:24 is still out. In fact, once you start looking at other biblically grounded alternatives to the Roman Catholic view, I get the sense that the doctrine of indulgences and purgatory are looking for a verse, like Colossians 1:24, to fit the theology, instead of looking at the text first, and then deriving the theology from the text and its Scriptural context. Roman Catholic apologist Karl Keating, in a debate with a Protestant apologist Dave Hunt, appeals to Colossians 1:24 to defend the “treasury of merit.” As Keating explains, the “treasury of merit” is not explicitly found in Scripture, but it is found in the tradition of the church, as handed down from the generations, from the original apostles. I am not sure how Keating can substantiate that view. Therefore, at the very least, one need NOT feel obligated to hold to the Roman Catholic magisterium’s view of indulgences and purgatory as the ONLY legitimate and binding approach to this difficult text. ↩