Has a new generation of scholars tried to overthrow the Apostle Paul’s teaching of justification by faith, by saying that Protestant luminaries like Martin Luther are wrong? Have these scholars denied the Gospel? Or have they recovered a crucial insight into Paul’s letters that has been there all along, hiding in plain sight?

If you have ever contemplated such questions, then chances are that you have heard something about the so-called “New Perspective on Paul.” Some think that the “New Perspective on Paul” is a recovery of what Paul originally taught in his New Testament letters. Others think that the “New Perspective of Paul” is suspect and even dangerous, if not downright heretical. The real answer is probably somewhere in between the extremes, but trying to figure out where to land on this controversy can be difficult to navigate for the average church-goer.

The most well-known popularizer of this “New Perspective on Paul,” otherwise known as the “NPP” is none other than world’s best known New Testament scholar, Nicholas Thomas Wright, or “N.T. Wright” as he is often called. N.T. Wright became famous within evangelical circles particularly in the 1990s, by taking on the radical scholars of the infamous “Jesus Seminar.” The critical scholars of the Jesus Seminar would take different colored slips of paper and vote on which sayings in the Gospels actually go back to the historical Jesus, and which ones were fictions simply placed on the mouth of Jesus by the early church.

Did the early church fabricate sayings from Jesus, thereby misrepresenting his actual message? N.T. Wright vigorously championed the idea that the Jesus of the Gospels is indeed the real Jesus, thereby strengthening the faith of evangelicals faced with such challenging questions. While not all sayings of Jesus in the New Testament were strictly verbatim records, these sayings nevertheless faithfully represented what Jesus actually taught. Any skeptic who wanted to cut the historical Jesus down to size had to contend with the sharp pen of N.T. Wright., as he eviscerated arguments against historic Christian orthodoxy right and left.

Since then, N.T. Wright has been a theological hero to many. I personally devoured Wright’s book in dialogue with the liberal Protestant scholar, the late Marcus Borg, The Meaning of Jesus: Two Visions when it was published, as Wright championed the historic, bodily Resurrection of Jesus Christ! Wright also defends the virgin birth, Jesus’ divinity, and Christ’s atonement for sins…. all doctrines that Marcus Borg finds incredible to believe. That book is a classic!!

But when it came to the Apostle Paul, a number of evangelicals began to have their doubts about N.T. Wright. It was Wright’s What Saint Paul Really Said that shook everyone up. For example, N.T. Wright was saying that Paul never taught the imputation of Christ’s righteousness for the salvation of the believer. Essay after essay from Reformed pastors poured out over the Internet, issuing dire warnings to the faithful who had fallen in love with the jovial bearded Anglican bishop. Was this British evangelical scholar’s enthusiasm for the NPP causing him to lose sight of the Gospel?

A younger generation of evangelicals took up N.T. Wright’s arguments with great enthusiasm, much to the consternation of the “old guard,” who were concerned that Wright’s influence was weakening the resolve of the church to uphold the faith once delivered to the saints. Like teenagers pushing the limits on their curfew imposed by their parents, N.T. Wright emboldened a kind of respectable rebellion among younger evangelicals, tired of the same-old same-old. In a culture which tends to favor the “new and glitzy” versus the “tried and true,” the concerns of the “old guard” are not without merit. Yet to these younger evangelicals, the “old-guard” came across sometimes as sweet yet curmudgeonly grandparents complaining about the clothes young people are wearing these days.

But was N.T. Wright making any sense to anyone? Was he really throwing a knife-edge at the heart of the Gospel, as his critics claimed?

In response, the well-known Minneapolis pastor and Bible teacher, John Piper, wrote a whole book expressing his alarm and dissatisfaction with the teaching of Wright’s (and others), The Future of Justification: A Response to N T. Wright (2007). Wright responded with a book of his own, Justification: God’s Plan, Paul’s Vision (2009). So was Piper misreading N.T. Wright, or was Piper’s critique correct? Or to play on the name of the British scholar, was he N.T. Wright or N.T. “Wrong?”

N.T. Wright and his array of bookshelves, loose papers, and slightly tilted lampshades. This reflects my own study environment, but my wife would not approve of Wright’s untidy library…..On the other hand, N.T. Wright is a bit of a theological book nerd. What else would you expect?

Bring Out the Dining Forks for Jews and Gentiles Eating Together?

OR Bring Out the Pitch Forks??

Some think that the “NPP” has revolutionized how we understand Paul, more attuned to Paul’s original historical context. From that perspective, the “NPP” realizes just how much Paul is concerned about Jewish and Gentiles believers should be reconciled with one another, so that they can share meals together and enjoy fellowship.

Others are distrustful, and think that the “NPP” is an invention of scholars bent on corrupting the faithful, a passing intellectual fad. Some think that the whole debate over the “NPP” is rather obtuse, a bunch of fancy theological mumbo-jumbo.

Others simply want to know what the fuss is really all about. After all, one of the primary claims made by NPP scholars is that generations of Christians have been misreading the Apostle Paul’s letters, and getting Paul terribly wrong. But if we are getting Paul wrong, then that seems like a pretty important issue to resolve. Paul is indeed the most prolific writer in our New Testament. Christians should do their best to read Paul within his own historical context, and not rely on traditions known or unknown which can distort our understanding of the Scriptures.

This is where The New Perspective on Paul: An Introduction, by Kent L. Yinger can be of tremendous help in trying to sort through these issues. I only learned of Yinger’s book on the late Michael Heiser’s Naked Bible Podcast, though the book has been out now for 14 years. Thankfully, the book is fairly short. Only 130 pages. It can be read in an evening or two, though a careful study looking up each Scriptural passage and meditating on them would take a good bit longer. It serves as the perfect text for a non-scholarly person to get their head around what to many seems like a really complex debate, way over their heads.

Yinger gives the reader a summary history of how the controversy developed. Names like E. P. Sanders, often associated with being the founder of the New Perspective on Paul, and James Dunn, are introduced to the reader, with summary reflections as to how these various thinkers developed their ideas, and how they have even agreed and disagreed with one another. But the most helpful part of Yinger’s The New Perspective on Paul: An Introduction is a survey of the concerns that evangelical critics have made of this scholarly movement. What are the theological concepts at stake in the debate?

Yinger’s starting point is really simple: the Apostle Paul was Jewish. While this may seem like an obvious observation, unpacking what this means is at the very heart of this discussion. When Paul became a follower of Christ, after persecuting the Christian movement for some time, as a zealous Pharisee, did he “convert” to Christianity? Did he really give up Judaism altogether? Or was his experience on the road to Damascus more like an epiphany, or like an extraordinary sense of “calling” from God that he had never heard before, which totally changed the course of his life?

The concern here is what did his Road to Damascus experience do to his sense of being Jewish? How did this shape Paul’s ministry as Jesus’ primary designation of him as apostle to the Gentiles? Did Paul’s experience lead him to conclude that the Jewish understanding of the Law of Moses was deficient at its very core? Was Paul’s opposition to circumcision for Gentiles his only concern, or were there other elements of the Law that should be excluded as well?

The big question could be summarized this way: Did Paul really believe that Judaism was all about “works-righteousness”; that is, trying to earn your way to heaven by performing good works, or did Paul have a different understanding of what “works of the Law” meant? Or to put it differently, did Protestant Reformers like Martin Luther misrepresent all Old Testament Jews as believing in a kind of “works-righteousness,” thus unintentionally and wrongly suggesting that the New Testament preaches a doctrine of grace as an anti-thesis to this “works-righteousness” of the Old Testament?

Yinger addresses all of these sorts of questions in his book, without getting bogged down with needless theological jargon. Yinger’s concern in writing this book most practically is his desire to see a heightened attention to holiness. Too many Christians buy into the misleading idea that once you are “saved” that you do not have to pursue a life of holy living.

Yinger’s book is also aimed at grounding our theology with a robust engagement with Scripture. In The New Perspective on Paul: An Introduction, Yinger provides a helpful look at various texts found in the New Testament that have become crucial in understanding the debate over the “NPP.”

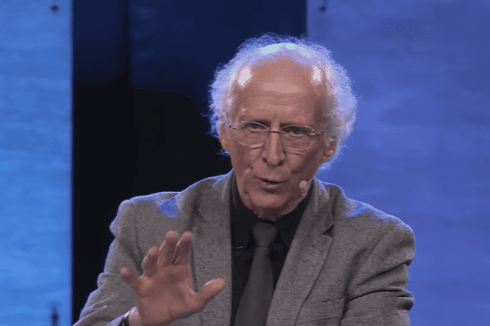

John Piper, America’s supreme defender of the doctrine of the imputation of the righteousness of Christ to the believer….. taking aim at the “NPP”…. notice the blue background, indicating that it is cold where he is speaking. Piper lives in Minneapolis, where the winters get very cold, so the setting is quite fitting.

What Does the Bible Say About the New Perspective on Paul? : Specific Passages

For example, in Philippians 3:6, Paul states that he was “blameless” before the Law. What did Paul mean by that exactly? For if it is impossible for someone to perfectly obey the Law of Moses on their own efforts apart from Christ, a key teaching in Reformation theology, then why on earth would Paul claim that he was “blameless” before the Law? (Yinger, p. 57)

Perhaps Paul was saying he was blameless before the Law in the eyes of others. Paul himself knew that his efforts at Law-keeping fell short, but others who saw his Pharisaical enthusiasm thought differently. That might be possible. On the other hand, it could be that Paul once thought of himself as blameless, before he met Jesus. It was only when Jesus met him that Paul realized just how much he fell short in perfect obedience, and that this sobering realization would matter greatly when it came to his salvation.

Nevertheless, proponents of the NPP would say that, sure, it was no problem for Paul to say that he was blameless before the Law, even as a believer in Christ. Paul could still be zealous for the Law and follow Jesus at the same time. Jews were perfectly free to continue with adhering to the Law, while still believing in Jesus. But for the Gentile, the story was different. The practice of circumcision, the key identity marker for a Jewish male, was completely unnecessary for the Gentile. Paul was adamant about that. Instead, what ultimately mattered and still matters for both the Jew and the Gentile, is that both must believe in Jesus.

Yinger does not try to resolve the debate between these different ways of reading Philippians 3:6. But this example tries to showcase why working through specific passages of Paul like this requires a good bit of reflection when trying to arrive at a good answer.

Yinger looks at other difficult texts, like Romans 7, Romans 10:3, Romans 4, Ephesians 2:8-10, 2 Timothy 1:9, and Titus 3:5-6, among others. ( I wish Yinger tackled 2 Corinthians 5:21, but alas he did not. This is my main criticism of the book, to ignore such a crucial text!)

Yet to keep the reader from getting bogged down too much in such interpretive debates, he also addresses the larger theological concerns that will hit the average Christian with greater impact: Is the NPP sneaking a “works-based” salvation back into the Christian life through some side door? Is the NPP undermining the concept of justification by faith, and faith alone? Yinger looks at these questions, summarizing the key arguments from each side .

“There’s Trouble in River City” : A Small Group Bible Study Crisis

A little anecdote here might help to demonstrate that the debate over the NPP is not just some obtuse theological matter. Like the song “Ya Got Trouble” from The Music Man, I can tell you a tale of “trouble right here in River City!”

Several years ago, my church had decided on a focused study of the Book of Romans for a year. Sermons were preached through the entire book, but for our small groups there was a booklet written by N. T. Wright, part of the N. T. Wright For Everyone Bible Study Guides series, which provided questions for our discussions.

However, within a few pages into the study booklet, Wright appears to say that Paul did not teach the imputation of Christ’s righteousness to the believer, as a way of showing what justification by faith actually looks like. The first problem was that there were several people in my group who grew up with the teaching about the imputation of Christ’s righteousness as a core element for understanding the Gospel. Others in my group had no idea what “imputation” even meant. Fiery discussion ensued.

Like the “pool table” in “River City,” the next few weeks of our Bible study was buzzing with trouble, trouble, trouble. But the trouble was about certain theological matters, substantially more weighty than the lyrics to a popular musical.

As a seminary trained person, I tried to suggest that the concept of the imputation of Christ’s righteousness; that is, whereby believers, who have no righteousness of their own, instead have the perfect righteousness of Christ credited (or imputed) to them, is not necessarily at odds with what N.T. Wright was fundamentally trying to get at.

If this concept of “imputation” means nothing to someone, it does help to consider that one way of thinking about “justification” is by breaking apart the word itself with a phrase that is easily memorized: “Just-if-I-had-never sinned.” For many Christians, this is a shorthand way of saying that when God looks at a believing Christian God is seeing us “clothed in the righteousness of Christ,” as opposed to seeing us in our sin.

That is one way of briefly describing the mechanics of “justification” by faith. So, the idea of “imputation,” an idea borrowed from a bank accounting metaphor, articulates in more detail how justification is then applied to the Christian; that is, the mechanics of how justification by faith “works” (no pun intended). As Martin Luther said in his 1520 The Freedom of the Christian, there is a “happy” or “glorious exchange,” whereby we as lost sinners have our sin transferred to the cross of Christ, and in exchange we receive the perfect righteousness of Christ that purely belongs to the risen Jesus. As a result, we who are guilty of sin (and know it!) have a verdict of “not-guilty” imputed, or credited, to us, enabling us to stand in God’s presence receiving the perfect acceptance of God’s love. This is all due to what Jesus accomplished by dying on a cross some 2,000 years ago, and being risen from the dead, which took away our sin so that we might be made presentable to a Holy God.

N.T. Wright, on the other hand, has said that the Apostle Paul teaches that the boundary markers for being members of God’s people have shifted with the coming of the Messiah Jesus. Where before the boundary markers for being a part of God’s people were defined by circumcision and Israelite ethnic identity, in the Gospel those boundary markers have been extended out to include the Gentiles.

For Wright, the Jewish problem was that they were too ethnocentric. Another way of putting it, in a more catching way of saying it, is that the Jews were more concerned about “race, instead of grace.”

In this perspective as Wright articulates it, the idea of “imputation” of righteousness is not really in Paul’s view. Instead, Paul is concerned about God’s righteousness in terms of God keeping his promises; that is, God is always “in the right.” Ultimately, the God of Israel’s big promise was that the Gospel announced in Jesus is not just for the Jews, but for the whole world. In other words, the doctrine of imputation is not necessarily wrong. It just is not what Paul explicitly had in mind.

I encouraged my small group to consider things differently, a third way through the debate: That you can have a concept of imputation of Christ’s righteousness, or at least something rather close to it, while still affirming the idea that God has extended the boundary markers for defining God’s people to include the Gentiles. The two ideas are not necessarily in conflict with one another.

On the one side, it could be that certain upholders of the Reformation, who want to defend the principled doctrine of justification by faith and faith alone, are missing something vital to Paul, which N.T. Wright and others are trying to illuminate. As I have thought of it in recent years, Wright indeed might be correct in saying that Paul does not explicitly teach a doctrine of imputation. Or Wright might be correct in saying that the concept of imputation does not adequately express all that Paul had in mind. Perhaps instead, a focus on our union with Christ, another core idea that goes back to the Protestant Reformation associated with John Calvin and Martin Luther, has a firmer grounding in Scripture. Our union with Christ might satisfactorily parallel the intent behind the Reformation doctrine of imputation, and better convey the core truth about what it means to be justified by faith.

At the same time, Wright’s earnestness in propounding his thesis could be just as stubborn as the efforts to dismiss Wright’s quite helpful insights all too quickly. Wright might be going too far if he is suggesting that imputation, or something like it, has no implicit basis in Scripture. A more sympathetic hearing is needed on both sides. In other words, there is no need to have a false dichotomy here.

The New Perspective on Paul is Correct In What It Affirms…. But Wrong In What It Denies

Not all core doctrines of the Christian faith are explicitly expressed in Scripture. Look as hard as you can but you will never find a direct statement saying that “Jesus is God.” The term “Trinity” is never once mentioned in the Bible, and the direct popular slogan, “One God, Three Persons” is missing as well.

Yet it would be wrong to say that there is no implicit teaching about the divinity of Jesus or the Triune identity of God. The challenge is that the data points for these various core doctrines are scattered across the pages of Scripture. One must think through how the dots are connected together in order to discover the truth that the Bible is illustrating. Furthermore, just because someone says that they believe in the divinity of Jesus or the doctrine of the Trinity does not necessarily mean their understanding of such things lines up well with Scripture. Likewise, while the doctrine of the imputed righteousness of Christ, or at least something close to it, is not explicitly and neatly defined in Scriptural proof-texts, this does not mean that it is not there in the pages of the New Testament.

The contrast between that classic Reformation theology championed by Martin Luther and the best insights of the New Perspective on Paul may not be at such odds with one another as so many people think. Sure, there probably is more than a little hubris displayed by certain scholars who take unfounded joy in saying that everything you thought you knew about the Apostle Paul is completely wrong. Some scholars favorable to the “NPP” do go overboard by even rejecting certain tenets of historically orthodox Christian faith. The “NPP haters” club is not wrong in pointing out that there are extremists in the “NPP lovers” club.

At the same time, you could also say that certain “NPP haters” are more interested in defending their tradition than in taking a fresh look at Paul’s letters. Perhaps the “NPP-is-awesome!” crowd and the “NPP-is-terrible!” crowd both have something to learn from one another.

As I have heard it said more than once: The New Perspective on Paul is correct in what it affirms… but wrong in what it denies.

This should not be controversial, but in some quarters it is: We know more now about the Second Temple Jewish context in which the New Testament and Paul’s letters in particular were written than what Calvin and Luther knew 500 years ago. The 20th century discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls alone has stimulated a revitalized interest in the thought world of Paul and his first century Judaism background.

At the same time, we can also learn from traditional ways of thinking about the Bible that have long since been forgotten. A lot of churches do not educate their people well about the history of the church. Too many folks could care less about things a couple of dead white guys from Europe said in the 16th century, and that is a terrible tragedy. Some might easily confuse “Calvin” with “Calvin Klein” blue jeans, or confuse “Martin Luther” with the civil rights activist, “Martin Luther King, Jr.” Therefore, it does take some thoughtful effort in navigating how to read various texts in the New Testament more carefully, and connect all of the dots of Paul’s theology, situated within the context of 2,000 years of church history, from earliest days of the apostles, up through the Reformation, and beyond.

What I Learned From My Small Group Bible Study Crisis

I thought that I had a set of good answers to give to others who had questions about the “NPP.” But it turned out to be rough sledding for my small group, and some other friends of mine in my church. The sermons continued to be given week after week without any discussion of the controversy that was lurking in our small group and other small groups in our church. The lack of dialogue across the church at large proved to be a missed opportunity to grapple more deeply with Paul’s letters.

After several weeks, the confusion about these topics eventually forced our group to abandon reading the N.T. Wright book altogether, and just stick with talking about what we were reading in the Book of Romans alone. Other small groups in my church did the same. This was rather unfortunate (and in my opinion, unnecessary) as there were topics of discussion in Wright’s little book that could have better helped us to read Romans more clearly. But at the same time, I had sympathy for those who felt confused. These issues are indeed difficult to work through without carefully studying Romans verse-by-verse, and asking probing questions along the way.

Looking back over this episode from several years ago, I wish I had a copy of The New Perspective on Paul: An Introduction by Kent Yinger to give to everyone in my small group and my church at large to help them navigate through the controversy. It would have probably prevented a lot of confusion from boiling over to become pure frustration and/or disenchantment.

The New Perspective on Paul: An Introduction, by Kent L. Yinger. A great introduction to an often contentious and vitally important debate.

A Recommendation for The New Perspective on Paul: An Introduction

The debate over the precise understanding of Paul’s teaching on justification has been going on for centuries, particularly since Martin Luther. Even if one believes that the NPP has taken a wrong turn here or there, the controversy over the NPP is hopefully taking the church in the right direction, adding new insights into Paul’s original cultural context while simultaneously sharpening our appreciation of Martin Luther’s Reformation perspective of the Gospel.

Yinger’s The New Perspective on Paul offers a modest defense of the NPP while engaging legitimate concerns from defenders of the classic Reformation view of doctrines like imputation, and the larger doctrine of justification by faith. As other reviewers have noted, Kent Yinger does a great job in framing this all too important discussion. Yinger will not resolve every angle of how to interpret this passage or that passage, but at least the reader will gain an appreciation of the challenges of trying to get Paul right.

While N.T. Wright is the most recognizable name associated with the NPP, he is not the only one, and a number of other NPP scholars have some serious disagreements with the British Anglican theologian. When it comes to N.T. Wright, the most influential evangelical voice representing the NPP, I have wrestled for years trying to work through his arguments. I have been both blessed by his work as he is a fascinating writer, while still harboring some concerns and principled disagreements along the way. I particularly loved Wright’s biography of the Apostle Paul, even while wincing a couple of times (See this review on Veracity).

However, a major problem with Wright is not strictly theological. The fact is that the man is a writing machine. He keeps pumping out book after book almost every year, and it is simply overwhelming to keep up, even for other scholars! Wright’s magnum opus on Paul, Paul and the Faithfulness of God, comes in at a whopping 1,700 pages! Who has time to read stuff like this?

Thankfully, Kent Yinger’s little 130 page book (according to Kindle), The New Perspective on Paul: An Introduction, is a lot easier to digest, for the theological novice. I am still working through some of the ideas in Yinger’s book, but I have found it really helpful. So if the NPP puzzles you, start with Kent Yinger’s book. He will help you navigate through the on-going discussion about what Paul is really saying in our New Testament.

For another look at the New Perspective on Paul, look at Preston Sprinkle’s five-part blog series (#1, #2, #3, #4, #5). I blogged about nine years ago, when my small group was in crisis, on N.T. Wright and the “NPP.”

What do you think?