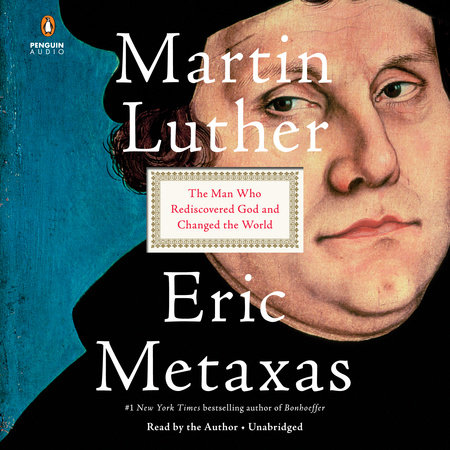

A warehouse at Auschwitz, storing clothes of camp victims, after liberation in January 1945. How much did Martin Luther’s rhetoric lead to the Holocaust? (Credit: National Archives)

Martin Luther is one of my theological heroes. But like any other fallen human, Luther was far, far from perfect. He was the Reformation’s chief champion of salvation by faith, and faith alone. But he also had a dark side… (NEWS FLASH)… just like you and me.

As we remember the 500th anniversary of when this obscure monk, turned bible professor at a university in Wittenberg, famously nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the church door, on Halloween, we mainly think of Luther’s attack on the abuses of the medieval Western church, a corrupt institution that instilled fear and anxiety among the people, and financially profited from such abuses. We also think of Luther’s famous stand for the Scriptures alone (sola scriptura), as the ultimate source of truth. I could go on with praises for Luther. We all owe an immense amount of gratitude to God for raising up a Martin Luther.

Luther was also a man who enjoyed life. He enjoyed good food, and having a good time with friends and family. He was comparatively more jovial than his later Reformed counterpart in Geneva, John Calvin. You could count on having a fun night, out on the town, with Martin Luther. With John Calvin? Well, you would probably be in bed before 9pm.

Luther preached a Gospel of grace, and grace alone…. and for the most part, he lived it.

I am a Martin Luther guy.

But this does not tell the whole story about Martin Luther. Luther had his blind spots, his dark side, if you will. To ignore these shortcomings is to fail to tell the whole story. There are possibly three elements to Luther’s legacy that still haunt the great German Protestant Reformer. Continue reading