As the summer of 2025 has been drawing to a close, I ran across some old photos of a summer trip to the Midwest, about twelve years ago, that I would like to share. My wife’s family is from Evansville, Indiana, which is not far from Interstate 64, taking one highway west from where we live in Williamsburg, Virginia to get there. Just a little over halfway to Indiana, about an hour northeast of Lexington, Kentucky, is a little spot off the road called “Cane Ridge,” not too far from the small town of Paris, Kentucky, in horse country.

Most people have never heard of Cane Ridge, Kentucky. The ridge was named by the explorer Daniel Boone, during the early decades of the American republic. But if you are a student of American church history, you should probably know about it, because Cane Ridge, Kentucky was the site of one of the most remarkable events of Christian history.

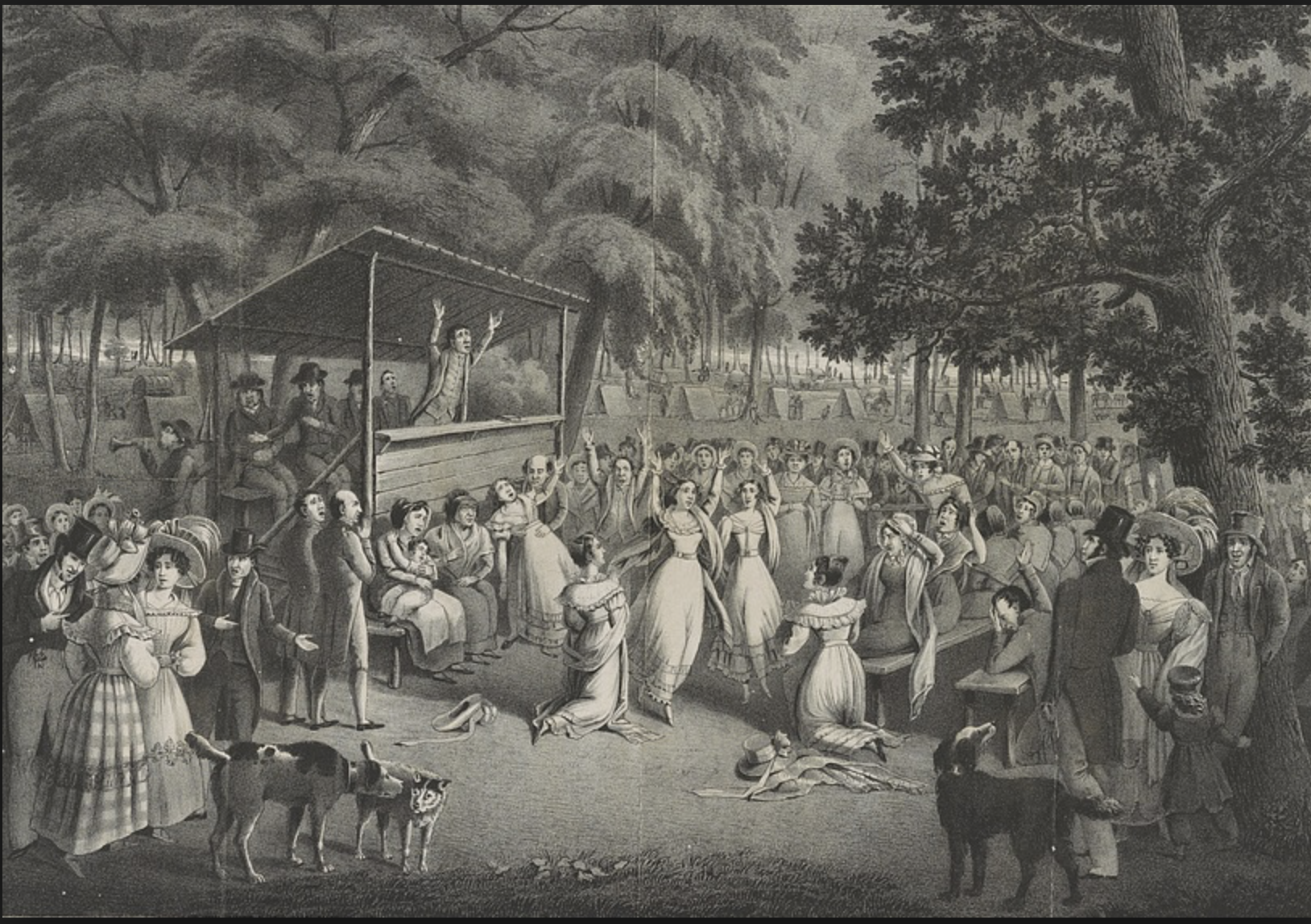

Sinners gathering on the “anxious bench,” during the American Second Great Awakening, in the early 19th century. The “anxious bench” was the forerunner to the modern “altar call.” This portrait envisions what the camp meeting at the Cane Ridge Revival might have looked like.

The Woodstock of the 19th Century

In 1801, a group of ministers were hoping to host a camp revival meeting in what was then the frontier of the young nation of the United States. The two most prominent figures in the movement were originally a Presbyterian minister, Barton Stone, and later on, a Scottish minister, Alexander Campbell. During the heat of the summer, there was not that much to do while your crops were growing on the frontier before the fall harvest, so the idea of traveling to a camp meeting was a great way to accomplish spiritual and social goals for folks spread out in sparsely populated areas of the Midwest.

What was unique about the Cane Ridge Revival was the sheer size of the event, for that moment in history, out on the American frontier. Stone and his fellow ministers behind the revival had advertisements for the camp meeting posted in numerous newspapers across the country. Historians estimate that in August, 1801, somewhere between 10,000 to 20,000 people descended upon Cane Ridge. It was the 19th century cultural equivalent of the 1969 music festival, Woodstock, held in New York state, a defining moment for the counterculture movement of the 1960s.

So many people came to the camp meeting that the house used by the little Presbyterian church, which hosted the event, could not be used. Makeshift platforms were made across the various fields surrounding the church building, where singers sang, and most importantly, preachers preached. In front of some of these platforms there was an “anxious bench,” where various sinners could sit when the message being preached pricked their hearts, urging them on to repentance. The “anxious bench” was the forerunner to the “altar calls” held by 20th century preachers, like Billy Graham.

When I met up with the local historian who was on-site, he told me that there were reported manifestations of healings, speaking in tongues, and being “slain in the spirit.” He even told me that some additional, really bizarre stuff was reported, too, like people barking like dogs.

Barton Stone, who led the little Presbyterian church at Cane Ridge, reported on the meeting like this: “Many, very many fell down, as men slain in battle, and continued for hours together in an apparently breathless and motionless state — sometimes for a few moments reviving, and exhibiting symptoms of life by a deep groan, or piercing shriek, or by a prayer for mercy most fervently uttered.” Eventually, their condition would change, giving way first to smiles of hope and then of joy, they would finally rise “shouting deliverance” and would address the surrounding crowd “in language truly eloquent and impressive.” “With astonishment,” Stone exclaimed, “did I hear men, women and children declaring the wonderful works of God, and the glorious mysteries of the gospel.”

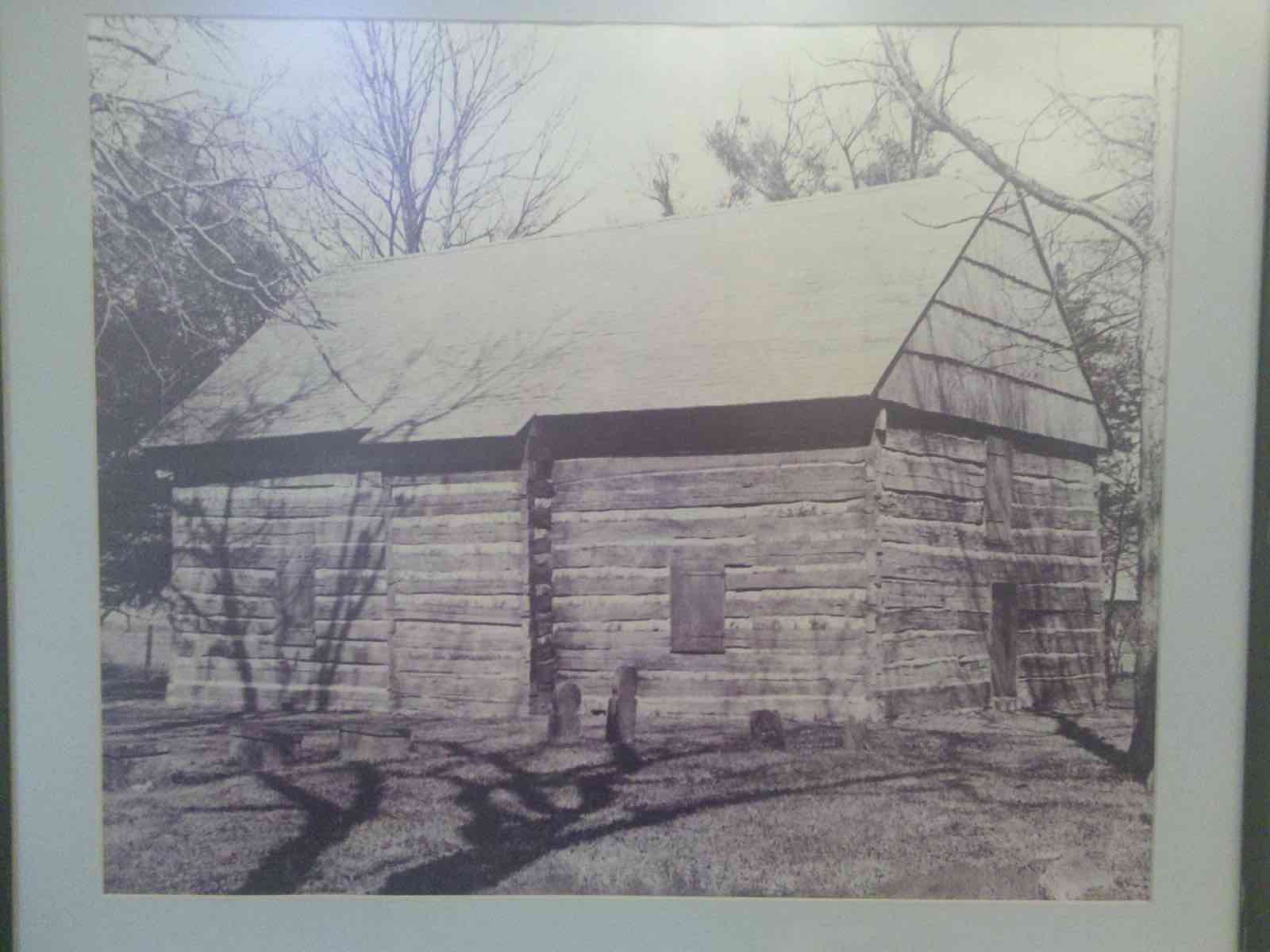

The original Cane Ridge meeting house, the Presbyterian church which hosted the 1801 revival. This photo was taken sometime in the early 20th century. I saw it as part of the Cane Ridge museum exhibit.

Not Presbyterian, Not Baptist, Not Methodist….. Just “Christian”

Cane Ridge was a remarkably interdenominational event, where Presbyterians, Baptists, and Methodists all joined together, for the cause of calling people to give their lives to Jesus. At the end of the week-long or so meeting, those remaining at the camp all shared in the Lord’s Supper together. It was a potent experience of Christian unity and spiritual energy. In many ways, the Cane Ridge Revival ended up spinning off numerous other camp meetings across the Eastern United States for decades, prior to the advent of the American Civil War.

Barton Stone and subsequently Alexander Campbell became the leaders synonymous with the movement, which often is called by historians as the “Restoration” movement. The idea was that Stone and Campbell believed that these various camp meetings, starting with Cane Ridge, were about restoring the Christian church to its original New Testament foundations.

During the early 19th century, groups like the Presbyterians, Baptists and Methodists were all defined by their various creeds and confessions. Visionaries like Stone and Campbell believed that these creeds and confessions just got in the way of sticking with what “the Bible says,” and calling people to faith and repentance, and following Jesus.

This Restoration movement was often associated with the popular slogan: “No Creed But the Bible.”

However, despite its “non-denominational,” or perhaps “inter-denominational” focus, the Stone-Campbell Restoration movement ended up spawning several prominent American denominations:

- Churches of Christ

- Disciples of Christ

- The Christian Church

- … and several others

As the original Cane Ridge church building was starting to fall in disrepair, an effort was made to preserve the wooden structure, by building another stone structure around it, in 1930. If you can imagine that inside the stone building behind me, stands the preserved wooden church building (see prior photo) safe from the elements, then that is what you would see if you visit Cane Ridge, Kentucky. The wooden building inside is one of the oldest structures standing in Kentucky.

After Cane Ridge

Barton Stone himself left the Presbyterian church, there at Cane Ridge, just a few years after the Cane Ridge Revival meeting. Stone was not content to sign off on the Westminster Confession of Faith championed by the Presbyterians any more. Instead, Stone merely called his group “Christians.” Alexander Campbell’s father, Thomas, was originally a minister enthusiastic about the Restoration movement, during that period of the Cane Ridge Revival. But it was the son, Alexander Campbell, who became a prominent minister himself among the “Disciples of Christ,” in the decades following the Cane Ridge Revival.

Several features were common to all of these groups. They all acknowledged the importance of water baptism for believing adults and celebrating the Lord’s Supper on a weekly basis.

However, there were notable differences, too, among these various groups, fault lines spreading out in various directions. For example, some groups emphasized that baptism was not simply a sign of one’s profession of faith, but it was also essential to one’s salvation. Some in the Churches of Christ refused to have musical instruments in their worship services.

I asked the on-site historian about what was behind the dispute about musical instruments. At first he told me that different Stone-Campbell groups would cite their own Scripture passages, for and against musical instruments in church. But he then conceded that the primary issue was economical. Most of these small churches, mostly scattered across the Midwest, were poor. By the time a church grew large enough to afford something like a piano or an organ, the community was often faced with a crisis: Do you spend your limited church funds on something like an expensive piano or organ, or do you increase the pay of your minister, or even better yet, fund some missionaries to go out and start some new churches?

While idealistic in many ways, the Restoration movement pioneered by ministers like Barton W. Stone and Alexander Campbell got involved in various controversies. Stone, for one, became outspoken in his opposition to slavery. Stone sought publicly to free several slaves that his wife had inherited from her parents. Kentucky law prohibited Stone from doing that in that state, as the slaves were legally connected to an estate. So, Stone moved his family to Illinois, where it was legal to free slaves connected to an estate.

However, at the same time, Stone became convinced that the classic doctrine of the Trinity was not biblical. Interestingly, he did not claim to be a unitarian, though he accepted a kind of subordinationism with respect to Jesus as the Son being subject to the Father.

Alexander Campbell was perhaps the more intellectually inclined of the two, emphasizing that Christian ministers should be college educated. Campbell founded the first institution of higher learning, Bethany College, in what is now West Virginia. In his earlier years, Campbell would engage in various debates, particularly in opposition to infant baptism. Yet he also engaged in a debate once where he defended the institution of slavery as being biblical (contra Stone).

Campbell’s relationship with the Mormons was complicated, as a number of Stone-Campbell movement adherents left the movement to become Mormons. Campbell wrote a critical review of the Book of Mormon, saying that the Mormons had added extra supposed Scripture to the Bible without warrant.

Today, the descendants of the Stone-Campbell are a very diverse lot. There are still conservative elements of those groups that still uphold many of the ideals that came out of the Cane Ridge Revival. However, the largest denomination, the United Churches of Christ (UCC), grew out of several Restorationist and other churches to form what has become one of the most prominent liberal mainline Protestant church bodies. The UCC at the denominational leadership level has been known for its support for abortion rights as well as support for same-sex marriage.

A Reflection on the Stone-Campbell Movement

Today’s adherents to the original principles of the Stone-Campbell Restoration movement often have a mixed view of creeds and confessions. On the one hand, the revivalist heritage of the Cane Ridge Revival put a rightful focus on the importance of conversion and having a personal encounter with Jesus Christ.

Nevertheless, while the famous adage “No Creed But the Bible“ may sound great at first, it belies a problem that has surfaced throughout the history of the Restoration movement, and other similar attempts to transcend denominational differences. In an effort to get rid of the objectionable creeds, many Restoration groups ended up re-engaging the same debates that led to the historical creeds in the first place.

The fact that an effort to promote a “non-denominational” form of Christianity ended up spawning a whole host of denominations, anyway, should tell you something. Particularly in areas of the American Midwest, just about in any town, you are within a stone’s throw of hitting a “Christian Church, “Disciples of Christ Church,” or a “Church of Christ.” Furthermore, in a number of cases, particularly in the post World War 2 era, the “No Creed But the Bible” mantra has become a cloak for hiding a tendency towards embracing “progressive Christianity.”

While there are many the positive elements that sprang from the Cane Ridge Revival, and the subsequent Stone-Campbell Restoration movement, having an aversion to creeds does not bode well for the future of the church. True, some creeds and confessions can get really deep into the weeds, making too many demands on the conscience of the believer. But in the world of Protestant evangelicalism which I have immersed myself now for decades, the lack of any creed, or downplaying such a creed, can be a recipe for theological crisis, ironically leading to more church splits, and not less.

The base level creed for classic Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Eastern Orthodox churches is the Nicene Creed. In 2025, we celebrate 1700 years since the Council of Nicaea met to hammer out the first draft of this creed that unites all of Christendom. If anything, the Nicene Creed should be something that all of us as Christians can start with.

The fact is “No Creed But the Bible” is a creed, in and of itself. Unfortunately, it is not a very good one.

Barton Stone Memorial obelisk, marking Stone’s grave at Cane Ridge, Kentucky. Though Stone died in 1844, his remains were interred at Cane Ridge in 1847. My wife and I stopped by and visited Cane Ridge, Kentucky, in August, 2013, the same time of year the Cane Ridge Revival was held in the summer of 1801.