“This is your friend, Elisabeth Elliot“….

If you could name just one woman as the most influential evangelical Protestant “saint” since World War 2, Elisabeth Elliot would probably be her.

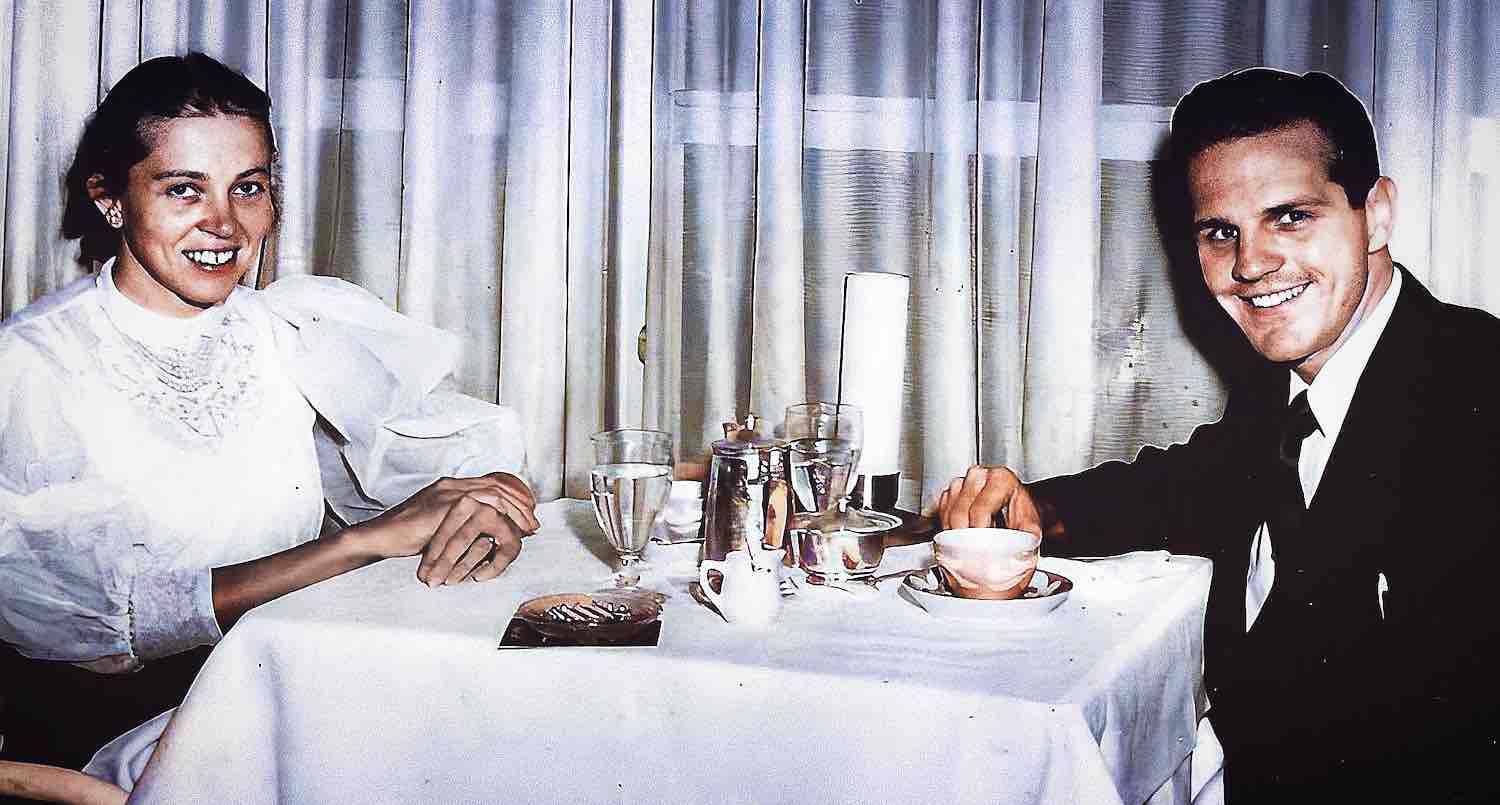

Elisabeth Elliot was the wife of martyred missionary, Jim Elliot, who along with four other men, died in their attempt to share the Gospel with Ecuador’s reclusive Waorani tribe in the 1950s. After her husband’s death, heavily publicized by Henry Luce’s LIFE magazine, Elisabeth wrote the evangelical classics, Through Gates of Splendor (1957) and Shadow of the Almighty: The Life and Testament of Jim Elliot (1958), catapulting her to be one of the most sought after authors and speakers in the evangelical publishing and speaking world.1

One of the biographies by Ellen Vaughn, about Elisabeth Elliot, which I read for this Veracity blog post series. Becoming Elisabeth Elliot covers the early years of Elisabeth’s life.

Before she died in 2015, Elisabeth Elliot had been a regular speaker at InterVarsity Christian Fellowship’s national conferences. In fact, in the 1970s, she was the first woman to be highlighted as a plenary speaker at the Urbana Missions conference, which InterVarsity holds every three years for college students. Her 1984 Passion and Purity: Learning to Bring Your Love Life Under God’s Control influenced the courtship movement popularized particularly in the 1990’s. Elliot was also a staple in the world of evangelical radio, with her syndicated “Gateway to Joy” program, which ran for 13 years. Elliot was practically minded in her teaching, and yet an intellectual at the same time.

My wife still listens to daily reruns of “Gateway to Joy” on the Bible Broadcasting Network. The tag line in each episode is permanently etched in my mind: “This is your friend, Elisabeth Elliot.”

Fascinatingly complex, Elisabeth Elliot was both an inspirational and polarizing figure. She championed the cause of missionary work, a direct influence on me as I read Shadow of the Almighty back in my college days, a recollection of her first husband and missionary, Jim Elliot. I marveled at the courage and conviction of Jim and Elisabeth Elliot, their mutual heart to reach lost people with the Good News of Jesus, and their willingness to do difficult things for the sake of following Christ.

One of Jim Elliot’s quotes was, “He is no fool who gives what he cannot keep to gain what he cannot lose,” from a journal entry Elisabeth preserved and shared to readers as an author of more than 30 books. She was a profound influence on the lives of many evangelical thought leaders, like Joni Eareckson Tada, and Timothy and Kathy Keller. In her later years, she regularly spoke at homeschooling conferences and Bill Gothard’s Institute in Basic Life Principles events. A young author, Josh Harris, wrote the 1990s evangelical blockbuster I Kissed Dating Goodbye, with a prominent endorsement given by Elliot, one of the primary texts in that decade promoting “purity culture.”

Elliot’s legacy is still revered in many evangelical circles, but this legacy has since come under scrutiny, particularly among younger and more disillusioned readers. Controversially, Josh Harris has since renounced his Christian faith and persuaded the publisher to stop selling copies of I Kissed Dating Goodbye. Harris had become convinced that Elliot’s theology, which promoted “purity culture,” was severely misguided. Bill Gothard, once a well-sought-out resource person for Christian homeschoolers, was forced to step down from Christian ministry, due to accusations about sexual harassment and grooming. Undoubtedly both attractive and controversial, Elisabeth Elliot’s life was anything but boring.

Elisabeth Elliot was a household name for about 50 years for many American Christians until her radio broadcast ended in the early 2000’s. Yet despite her influence, there are still many Christian young people growing up today who know nothing about Elisabeth Elliot.2

It is a complicated legacy, but one worth telling, acknowledging that Elisabeth Elliot was a remarkable, exemplary Christian figure, while still possessing very human faults.

Early Years of Elisabeth Elliot: Growing Up as “Betty Howard”

Elisabeth grew up in a missionary family, who served in Belgium after the end of World War I. Her parents, Philip and Katharine Howard, had married one another in 1922, despite the fact that Philip had lost an eye in an accident with a firecracker, wondering if any woman would ever love him. They spent five years together with the Belgian Gospel Mission, living in the aftermath of the “Great War.” Upon the family’s return to the United States, Elisabeth’s father eventually became the editor of a popular evangelical publication, The Sunday School Times, out of Philadelphia.

Her closest family and friends knew her as “Betty Howard,” but as she grew older, and into the public eye, she became known as “Elisabeth.” Her interest in missions was inspired by the many missionary guests who visited the Howard home, sitting around the dinner table telling stories. One of the most memorable visits was from Betty Scott, a very bookish-looking young woman preparing to serve with the China Inland Mission. Betty Scott was on her way to China, where she eventually met up with another missionary, John Stam, and the two were soon married, and had a baby daughter.

As biographer Ellen Vaughn tells the story, Betty Howard was but a young child as she listened to Betty Scott’s conversation with her parents. But just a few years later, in 1934, Betty Howard heard the news that John and Betty Stam had been murdered by Communist soldiers. The Stams had been marched from their China home to a nearby village, with their young baby. The next morning, the Stams had hidden their baby in a pile of blankets, while they were bound and taken out to the village center, and brutally beheaded, along with a Christian shopkeeper, who tried to intervene and stop the soldiers from killing the missionaries. Their baby daughter was found hours later, by other Chinese believers, with a note pinned to the baby’s clothes, with enough money for the baby to be sent back to America to be raised by her aunt and uncle.

The story of John and Betty Stam’s martyrdom indelibly stamped a mark upon young Betty Howard. As a teenager, Betty Howard spent several years at a Christian boarding school in Florida, followed by her years in college at Wheaton College near Chicago, with an additional year at Prairie Bible Institute, in Alberta, Canada, before going off as a full-time missionary to Ecuador in 1952. Little did she know that within just a few years after arriving off the boat into Ecuador that she herself would be the center of a tragedy which made its way into worldwide headlines, making her into an evangelical Christian icon.

From Betty Howard to Elisabeth Elliot: Biographies Which Tell Her Story

Though the future Elisabeth Elliot was raised in a staunchly Protestant conservative, American missionary family, her brother Thomas Howard in adulthood left evangelicalism to become Roman Catholic, after teaching English at the evangelical Protestant Gordon College. Howard’s move to Roman Catholicism shook many Protestant evangelicals who found Roman Catholic doctrines incompatible with evangelical Christianity. Before his death in 2020, Thomas Howard, like his sister, had become a prolific author, though he wrote influential books in defense of Roman Catholicism.

Aside from her contribution to missions, Elisabeth Elliot has probably been known best for her teaching on the relationship between men and women, both in marriage and in the church. As an advocate for a particular kind of evangelical complementarianism, Elisabeth became an outspoken opponent to evangelical egalitarianism, a theology that teaches that it is permissible for women to serve as elders in evangelical local churches, and that “male headship” in marriage as traditionally interpreted is a flawed reading of Scripture. Elliot also subscribed to the theological view that Jesus as the Son of God is and has been eternally functionally subordinate to the Father, as a model for a wife’s submission to her husband, a view that even other complementarians have rejected as heretical.

Several books have been published in recent years which have sought to chronicle Elisabeth Elliot’s life. In 2019, Elliot’s only child, Valerie Elliot Shephard, published some commentary and excerpts from her mother’s diaries and correspondence between her mother and Jim Elliot, during their long courtship, Devotedly: The Personal Letters and Love Story of Jim and Elisabeth Elliot.

In 2020 and 2023, author Ellen Vaughn published two volumes for an authorized biography of Elliot’s early life, Becoming Elisabeth Elliot, and a biography of Elliot’s middle years, Being Elisabeth Elliot, respectively (Vaughn has decided not to publish a work corresponding to Elliot’s later years).

However, it is the 2023 biography by Lucy S. R. Austen, Elisabeth Elliot: A Life which has drawn most of my attention. Through this blog post, and two follow-up blog posts, I hope to cover three overlapping periods of her life, with a center point for each post being a focus on each of the three successive marriages Elisabeth Elliot had, highlighting moments that stood out to me in Austen’s biography.

In the footnotes, I will occasionally make reference to material found in Vaughn’s biographies, and Shephard’s book, Devotedly. Austen’s biography took me about 26 hours to finish on Audible, and the two biographies by Vaughn took me about 24 hours combined to finish. In the third blog post, I will offer some critical reflections on the work by each author.

A Life Marked By Suffering and Obedience to Christ

A common thread for all three of these authors is that Elisabeth Elliot’s life was marked by very profound tragedy and suffering. Elisabeth penned these words as a student at Wheaton College in the late 1940s:

Perhaps some future day, Lord,

Thy strong hand

Will lead me to the place where I must stand

Utterly alone

Alone, O gracious Lover, but for Thee

I shall be satisfied if I can see

Jesus only

I do not know Thy plan for years to come,

My spirit finds in Thee its perfect home,

Sufficiency

Lord, all my desire is before Thee now;

Lead on—no matter where, no matter how,

I trust in Thee

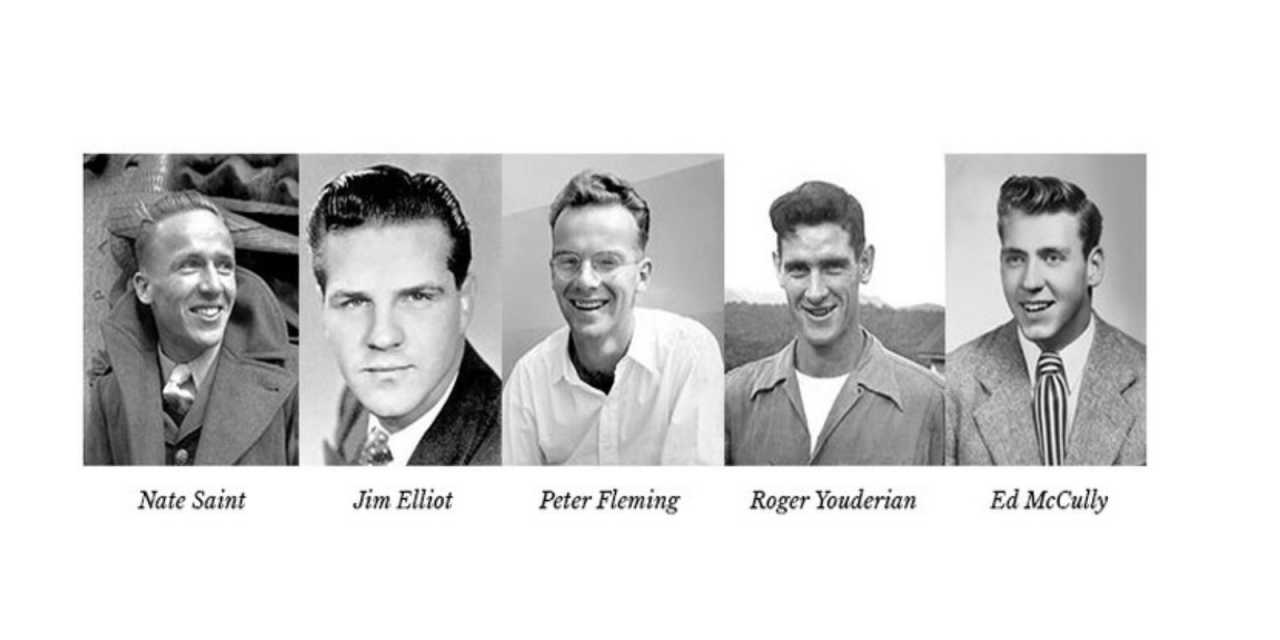

The most well-known story from her life is the incident when Jim Elliot, who had only been married a few years to Elisabeth, who along with four other missionaries, were speared to death by the Ecuadorian Waorani, leaving Elisabeth as a widow and a mother to young Valerie. The Elliots and their missionary colleagues had been trying to reach the Waorani, an unreached people group, but they wanted to make contact with the Waorani before the Ecuadorian government might place restrictions on their missionary activities.

It was a precarious situation as the Waorani had a reputation for killing outsiders who ventured too close. Despite such concerns, the missionaries pressed on, trusting that God would find a way for them to make friendly contact. Sadly, what they feared the most transpired anyway, and Elisabeth Elliot and the other missionary widows had to wrestle spiritually with their grief, searching for a way to learn how to trust God and that God knew what he was doing.3

The five missionaries who died as martyrs in the Ecuadorian forests by Waorani men who feared them: Nate Saint, Jim Elliot, Peter Fleming, Roger Youderian, Ed McCully

Elisabeth continued to serve as a missionary in Ecuador for several more years, continuing the work her husband and others had started. She derived much of her perspective as a missionary from the example of Amy Carmichael, an Irish Christian missionary serving in India in the early 20th century. Carmichael was also a prolific author, writing mainly about her life as a single missionary. Carmichael died in India, just a few years before Elisabeth Elliot made the fateful journey to serve in missions in Ecuador.

However, Elisabeth eventually returned to the United States, where she focused on her efforts to be a writer, leaving her life as an overseas missionary aside. Elisabeth later remarried Addison Leitch, a professor at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. But Leitch died of cancer, leaving Elisabeth widowed yet again. In 1977, Elisabeth married a third time to a hospital chaplain, Lars Gren, who still survives Elisabeth. However, the last ten years of Elisabeth’s life was marked by dementia, which severely impaired her ability to continue writing, which is what she loved to do most.

Since Lucy Austen’s work covers the longest period of Elisabeths’ life, and it was the first biography of Elisabeth Elliot which I read,I have made observations in this book review regarding what stood out to me. Lucy Austen has a Substack blog where she writes about some of what went into her research into Elisabeth Elliot’s life (#1, #2, #3, #4, #5, #6). The references in this book review align with the chapter headings in the Audible audiobook version of Elisabeth Elliot, A Life, and not the print or Kindle versions of the same.

Courtship and Marriage to Jim Elliot

In her retelling of Elisabeth’s life story, based on Elisabeth’s diaries and letters, Austen observes that Jim and Elisabeth had assumed a particular method for discerning God’s perfect will, taught by Jim’s Plymouth Brethren community, and common to the Keswick Holiness movement’s vision of spiritual discernment that many Christians in Elisabeth’s era uncritically embraced. Elisabeth would commonly read one chapter of the Bible a day, reading the passage over and over, praying through the text, asking God to show her a new meaning in each verse (Austen, chapter 8).

In Jim and Elisabeth’s courtship, which lasted several years while they were in college together, through their period serving as single missionaries in Ecuador, they used this method for discerning God’s perfect will, as to whether or not the two should get married. From Song of Solomon 8:4, “I charge you, O daughters of Jerusalem, that ye stir not up, nor awake my love, until he please” (KJV), Elisabeth reasoned that she should not seek marriage but that she should let Jim bring up the subject, which led Elisabeth into years of frustration before finally Jim did pursue the prospect wholeheartedly.

During that waiting period, Elisabeth found it difficult to “sleep” in the will of God, waiting for Jim to move. Nevertheless, Elisabeth wrote in her journals that she was determined to continue to trust in God and his timing, and not let her feelings throw herself into a spiritual panic. She believed that her love life must be brought under the sovereignty of God and God’s plans and purposes for her life.

Jim’s feelings were complicated. At one point fairly early in the relationship, Jim told Elisabeth of his love for her but he hesitated at making a commitment. Jim had sensed a call to become a missionary, and he was told by others that such a job as he envisioned it required a singular focus that left marriage out of the picture (Austen, chapter 8).

Elisabeth communicated to Jim that they should focus primarily on their friendship, and nothing going beyond that. Rather than pursuing marriage at that stage, Jim longed for a type of same-sex friendship between him and another man, a type of Jonathan and David relationship, where the love between two men could surpass that of a woman. As Jim wrote in his journal, “Lord, give me a David.” Some have speculated that Jim Elliot might have been wrestling with homosexual leanings, but Austen never explores this possibility, and there does not seem to be much evidence beyond that of Jim Elliot simply looking for a purely non-sexual, deep male-to-male friendship (Austen, chapter 10).4

In Jim Elliot’s reflections on 1 Corinthians 11 (Austen says 1 Corinthians 7, but this appears to be an error), Jim explains much of how he viewed relations between men and women. Just as God is the head of Christ, where Christ is the body, so is man the head of woman, where woman is the body (1 Cor. 11:3). The head directs the body, so the man is to direct the woman, since woman is more driven by her “body,” in the sense of her feelings, as opposed to what her head tells her. The man is the image of God, covered by nothing aside from Christ, and then the man controlling the woman. The woman, the glory of man, is covered and controlled by man, just as man is covered and controlled by Christ, just as Christ is covered and controlled by God. So while both Jim and Elisabeth Elliot viewed the man as the leader with respect to the woman, the woman was responsible for regulating and limiting sexual activity (Austen, chapter 10).

Austen is rightly severe with Jim Elliot for declaring his love for Elisabeth, while simultaneously not expressing any commitment to her, while also simultaneously writing letters to her divulging his sexual desires for her (Austen, chapter 13). He was evidently confused, frequently vacillating between what he believed was a calling to live a celibate life in order to be obedient to the vision God gave him to be a missionary, while also longing for a helpmate to stand beside him in his life journey. It was an exceedingly complex courtship, which lasted for several years while both were in their early and mid twenties. But it eventually was consummated in marriage in Ecuador, after the two had worked together there for a few years as missionaries, among the native tribes peoples there.6

Following the death of her husband Jim, Elisabeth had the opportunity to write about the story of Jim and the other men who died as missionary martyrs. When the news of the killings reached the United States, Henry Luce’s LIFE magazine (Austen, chapter 22) sent a photographer to Ecuador to cover the story of the deaths of Jim Elliot, Nate Saint, Roger Youderian, Edward McCully, and Pete Fleming. Out of that encounter eventually came Elisabeth Elliot’s first and probably most well-known book, Through Gates of Splendor.7

This book made Elisabeth Elliot a household name in many conservative Christian households in the United States in the 1950s. But the then famous missionary widow continued on in Ecuador in hopes of carrying on her deceased husband’s calling. Despite her on-going suffering and grief regarding her husband’s death, she still felt called to reach the Waorani people with the Gospel, no matter what it cost her.

Elisabeth Elliot Shares the Gospel With the People Who Killed Her Husband

Within about twenty months after the deaths of the five missionaries, an opportunity arose whereby several Waorani women had traveled out of Waorani territory and made contact with the missionary community, including Elisabeth Elliot. This created a breakthrough enabling Elisabeth Elliot and fellow missionary Rachel Saint, sister of the deceased pilot and missionary, Nate Saint, to go live with the Waorani, living among the killers of the missionaries for several years. Having her young daughter, Valerie, accompany her in doing such dangerous and difficult work would shock many readers today, but for Elisabeth Elliot, the efforts she made to follow Christ were worth it.

Elisabeth frequently wrote in her journal about her own doubts and anxieties, but she would consistently return to the theme of yet “thy will be done” with respect to obedience to the command of God, trusting that God would guide her, whether she lived or died in the process. By the early 1960s, a number of Waorani people had become followers of Jesus. Elisabeth’s efforts with the Waorani had an impact on thousands of other believers who served God through missions.8

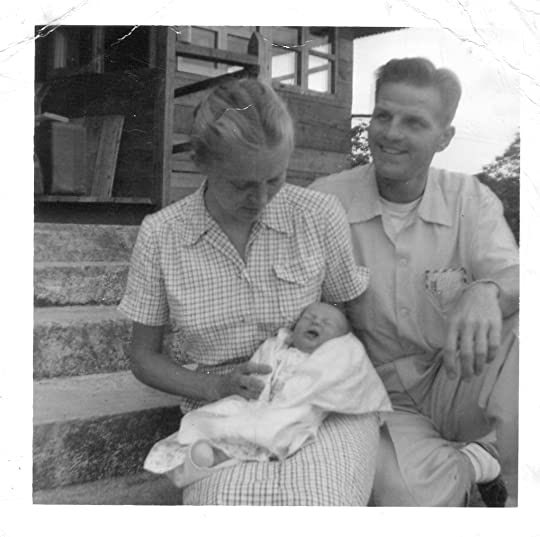

The wives and children who survived the deaths of the five missionaries in Ecuador, including Elisabeth Elliot and daughter Valerie.

Tensions On the Mission Field

Elisabeth Elliot’s relationships with other missionaries in Ecuador shows how conflict with other missionaries on the mission field can impede progress in the work to which one senses God’s calling. Though Elisabeth trained for a period with the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL) prior to going to Ecuador, Elisabeth had a falling out with SIL in Ecuador regarding SIL’s policy of working with Roman Catholic priests, such as allowing Catholic priests to ride in SIL sponsored airplanes to go visit various native tribes. However, her critical attitude towards SIL tended to soften somewhat in later years (Austen, chapter 15).9

But it was the day-to-day conflicts that Elisabeth had with some missionaries that gave Elisabeth quite a bit of angst. She even remarked that at times she got along better with the Waorani people than her fellow American missionaries.

The most difficult relationship Elliot had was with the sister of one of the dead missionaries, the pilot who flew the other male missionaries into the Waorani jungle homeland, Nate Saint. Nate’s sister, Rachel Saint, was twelve years older than Elisabeth. Elisabeth was twenty-nine years old when the missionaries were killed. After the killings, Rachel and Elisabeth were committed to continuing the outreach towards the Waorani people, but they had very different ideas as to how to accomplish the task. They did manage to make contact with the Waorani, and both women even lived with the tribe people for some time. The language acquisition work was slow, but step by step progress was being made. However, the cross-cultural stresses and strains triggered a rift between Rachel and Elisabeth that never seemed to heal.

Personality and mission strategy conflicts were not the only points of contention in Rachel and Elisabeth’s relationship. According to Austen, Rachel Saint had become seriously concerned that the younger Elisabeth was drifting away from Christianity (Austen, chapter 24). Elisabeth Elliot had raised questions about the eternal fate of one of the tribesmen who had met the missionaries, but who was later spear-killed by other Waorani who feared contact with the missionaries. Elisabeth had wondered if the words of Jesus in Matthew 10:40 might apply here:

He that receiveth you receiveth me, and he that receiveth me receiveth him that sent me. (KJV)

Since that man had welcomed the missionaries peacefully, without first hearing the message of the Gospel, would this have been adequate assurance that the man would indeed be going to heaven to be with Jesus? Rachel Saint believed in the abundant mercy of God, but she was bothered by the questions Elisabeth Elliot was asking. Rachel was also concerned about Elisabeth’s books, in that Rachel was not fully convinced that Elisabeth was adequately affirming the bodily resurrection of Jesus and of the future resurrection of believers.

Elisabeth had also written a letter to her mother regarding some questions about the intermediate state; that is, what happens to the believer when they die before Jesus comes back at the Second Coming to raise the dead and judge the world. Elisabeth was not sure if a deceased believer’s soul went to be with Jesus immediately upon death, or if the soul actually remained unconscious; that is, the doctrine of “soul sleep,’ a doctrine some Protestant groups say is in Scripture but that the vast majority of conservative evangelical Christians, presumably including Rachel Saint, tended to reject in favor of the former position.

Elisabeth had indeed moved away from certainty regarding various non-essentials of the faith, in her years as a missionary in Ecuador. But she had still clung to the essential tenets of Christianity. Nevertheless, Rachel Saint still felt a certain unease about the stability of Elisabeth’s faith.

It is difficult for me to fathom why Rachel Saint had such a critical perspective of her colleague Elisabeth Elliot. The doubts and questions Elisabeth Elliot experienced on the mission field were and still are not unusual. Perhaps it was Elliot’s willingness to speak her mind so freely with Rachel Saint, which upset the older missionary? But nearly twenty years after the death of the six male missionaries, Rachel’s sending missionary agency, Wycliffe Bible Translators, in conjunction with SIL, removed her from that field of work after an anthropologist was sent in to investigate concerns about Rachel Saint’s missionary methods and interactions with other missionaries. Rachel Saint eventually returned to work independently with the Waorani. She died in Ecuador in 1994.10

The disconnect between Rachel Saint and Elisabeth Elliot eventually prompted Elisabeth to leave Ecuador and missionary work, and return to the United States. For years, Elisabeth would tell others that she returned to the U.S. mainly because she wanted her young daughter Valerie to receive an education in the U.S. But Lucy Austen is persuaded that the rift between the two women is what primarily prompted Elisabeth’s exit from the Ecuadorian mission field.

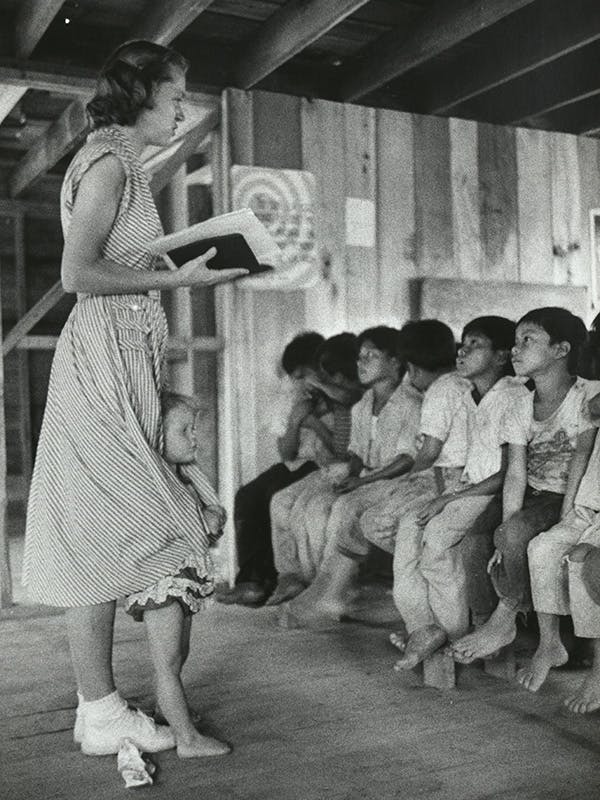

Elisabeth Elliot teaching the Bible to a native tribal group in Ecuador, with daughter Valerie playing with her dress. This photo was taken by LIFE photographer Cornell Capa, who became a good friend to Elisabeth Elliot. Capa, an agnostic, would not accept Elisabeth’s theology, but he respected her intellectual integrity.

Elisabeth Elliot, the Missionary, and Her Work as a Novelist

Elisabeth’s conflict with Rachel Saint, and her other disappointments on the mission field, influenced her efforts as a writer. Her 1966 novel, No Graven Image, now out-of-print, about a twenty-five year old single, female missionary to Ecuador is in many ways autobiographical (Austen, chapters 27, 28). In No Graven Image, the central character, Margaret, has romantic idealist expectations in going to Ecuador as a missionary, only to have a lot of those ideas challenged if not shattered. One other character in the book, a well-meaning but culturally insensitive American missionary executive, takes intrusive photographs of the Quechua Indians, refuses the native food served to him, and hands out gospel tracts written in Spanish to the illiterate Quechua, who knew little to no Spanish anyway.

Margaret’s efforts to reach the natives in the Andes Mountains are slow going, though she finally manages to gain a foothold with a man named Pedro in order to do Bible translation work. Tragically, Pedro dies, and others are suspicious about her as it is believed that Margaret poisoned Pedro with medicine applied to a wound Pedro had, which eventually led to his death. Apparently, Margaret had used penicillin, but Pedro was deeply allergic to penicillin.

Pedro’s death sent shockwaves through Margaret’s soul. She began to have serious doubts about her missionary calling. Was she really being useful in God’s purposes to reach these unreached peoples? Why would God lead her to Pedro to do Bible translation work, and then somehow allow Pedro to die on her? How could she trust God now after Pedro’s death?

The book asks a lot more questions than providing answers. In Walking with God through Pain and Suffering, Timothy and Kathy Keller cite Elisabeth’s No Graven Image, where the only consolation at the end of the book is: “God, if He was merely my accomplice, had betrayed me. If, on the other hand, He was God, He had freed me.”

When the book was published in the 1960s, No Graven Image received mixed reviews. Christian bookstores banned her book, refusing to sell Elisabeth’s novel, believing that the author was sending the wrong message to prospective evangelical missionaries. No Graven Image might have been the least liked of Elisabeth Elliot’s books during her lifetime, though it would hardly be that controversial if it was published today.

Harold Ockenga, one of the co-founders of both Fuller and Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminaries, met personally with Elisabeth Elliot to say that No Graven Image presented a “caricature” of the missionary enterprise. In his review of No Graven Image, Christianity Today editor Harold Lindsell sought to smooth away some of the criticisms of the book by contending that the negative images of evangelical missionaries portrayed in the book represented an “idiosyncratic” , “minority” view. As Austen comments, Elisabeth Elliot’s critics were responding to more than just the book. They were also responding to public perceptions at the time that American Christian missionaries were doing more harm than good in their efforts to reach unreached peoples with the Gospel (Austen, chapter 28).11 12

Elisabeth’s experience as a missionary definitely loosened her up regarding certain aspects of fundamentalist rigidity she learned when growing up. Her education at Wheaton College before going to Ecuador had made her aware of worldviews outside her particularly Christian bubble, but disillusionment with certain ways of thinking on the missionary field expanded her intellectual interests. Throughout her life going forward, Elisabeth would value and promote the writings of other authors who held theological views which were suspect in her strand of evangelicalism. For example, though not a universalist herself, Elisabeth grew to adore the writings of 19th century Victorian writer George MacDonald (a major and influential literary figure for C.S. Lewis), as well as the 19th century Keswick conference speaker, Hannah Whitall Smith. Both MacDonald and Smith embraced a kind of Christian universalism, suggesting that hell would eventually be emptied in the eschaton, and all humans reconciled to God.13

Austen notes that other missionaries who pondered certain doubts about their own faith were willing to confide with Elisabeth (Austen, chapter 27). But more often than not, Elisabeth’s journal entries regarding her encounters with other missionaries are often laced with acerbic commentary concerning some missionaries who seemed thoroughly one dimensional in their life outlook. At one point while still in Ecuador, Elisabeth was living in a house that Jim had once built for them, but who she now as a single mother shared with another missionary family who was not as fastidious nor as intellectually rigorous as she was, eventually forcing Elisabeth and her daughter to move out of the house.

Though it is not clear as to where she stood on the matter, Elisabeth interestingly noted in her diary that some of the other missionaries would not eat strangled chicken, if they knew about it, a common method of killing chicken in preparation for cooking in Peru, believing that this practice violated Acts 15:29 (Austen, chapter 25). But in other matters, Elisabeth was dismayed at how legalistic certain missionaries and other Christians in her circle could be, being opposed to behaviors such as going out to watch a movie.

Jim and Elisabeth Elliot had only been married to one another for a couple of years before Jim was murdered on the mission field. Valerie was less than a year old when her father was killed.

Elisabeth Elliot, Now the Former Missionary Turned Speaker and Author

When she returned for good to the United States to pursue her career as a writer, she was annoyed by invitations to speak about her missionary experience with different Christian groups where she was expected to give pep talks to generate enthusiasm for missions. Many of these speaking opportunities came across as shallow, wanting Elisabeth to conform to the image of a heroic, triumphant missionary doing “great things for the Lord.”14

The young, idealistic single female missionary who embarked to go to Ecuador in her mid twenties had returned to the United States in her thirties with a legacy of suffering, frustrated hopes, and a strong dose of realism. For Elisabeth, having months of your language translation work stolen and lost, not getting along with a few other fellow missionaries, and losing your husband to a violent and senseless death, will do that to a person. And yet, she would always return to the theme of obedience to Christ, serving God wherever God would lead her to go, trusting that his ways ultimately made sense, when in the moment they did not.

Even while serving in Ecuador, Elisabeth expanded her reading to include books written by authors well outside of the conservative evangelical bubble in which she was raised, like existentialist philosopher Albert Camus, and Susan Sontag, a secular literary critic. She often felt that secular writers were better about writing about truth than some of her fellow Christian writers. She also acknowledged that well-meaning Christians had done tremendous harm in hurting other people, even killing others, for the sake of doing things in the name of God. Such is the reality in a good bit of church history. (Austen, chapter 24).

When someone sent her a copy of a book by Andrew Murray, a popular Dutch Reformed author in the early 20th century, Elisabeth was disturbed by Murray’s message in his Divine Healing. To Elisabeth, Murray seemed to teach that Christians should expect to live out their lives to the “threescore years and ten” described in Psalm 90:10, and that believing Christians should never get sick. For Elisabeth, who still had great respect for Murray’s writings, his thesis in Divine Healing seemed wholly contrary to “reason,” and she therefore could not accept it (Austen, chapter 24).

Elisabeth sometimes found it difficult to discuss certain controversial matters, even with her own family, particularly when she returned to the United States permanently. She sometimes debated with her brothers about what mattered most in the Christian life. She would often highlight the ethic of love above any other absolute associated with Christianity.

Some have suggested that at this phase in her life, Elisabeth Elliot might be drifting away from historic orthodox faith, or at least shifting somewhat in a more progressive direction. For sure, Elisabeth was moving more in the literary progressive crowd, and reading even more widely. She conversed frequently with intellectually-oriented “Christian feminists.”

After a visit to Jerusalem in the 1960s, Elisabeth Elliot took a position unpopular at the time among many conservative evangelicals, that both Israelis and Palestinians had a right to the land, and not just the Israelis, a position she outlines in the now out-of-print 1968 Furnace of the Lord. Even years later, she wrote a controversial 1978 essay in Christianity Today, in support of the Arabs.15

But any concerns about Elisabeth’s orthodoxy or progressive leanings could be arguably put to rest when she eventually remarried. She married Addison Leitch, a college professor and editorial contributor to Christianity Today magazine. The middle-aged, former missionary who just a few years earlier swore that she would never marry again, eventually fell head over heels in love.

Elisabeth Elliot was changing in complicated ways. But her eventual three marriages each marked different phases of her life that often overlapped with each other. In the next blog post in this review, we move on from her life centered around the story of her relationship with Jim Elliot to her eventual relationship and marriage with Addison Leitch.

Link to the second blog post in this series.

Notes:

1. Older followers of Elisabeth Elliot will know of her work with the “Auca” people in Ecuador, but anthropologists today recognize that this term is a pejorative, according to one of her biographers, Ellen Vaughn. Following Vaughn, in this book review I follow the recommended terminology of “Waorani” to refer to the tribal people Elisabeth Elliot worked with, though some also use different terms, such as “Huaorani.”↩

2. Biographer Ellen Vaughn, in doing her research on Elisabeth Elliot’s life, went to Elisabeth’s alma mater, Wheaton College, to interview students outside of Elliot Hall and Saint Hall, named after two of the missionaries killed in the 1950s by the Waorani tribe, the first being Elisabeth’s husband at the time, Jim Elliot. Very few of the students she met at that school recognized the name, Elisabeth Elliot.↩

3. Biographer Ellen Vaughn reports that the secrecy among the missionaries concerning the outreach to the Waoranis was also due to concerns that the government might seek a military solution to resolve concerns about the Waorani, causing some of the missionaries to fear that the future of the Waoranis was in serious doubt. The Shell Oil Company had tried to start drilling operations in the Waorani part of Ecuador, for a little over a decade before the missionaries were murdered. But after several deaths at the hands of the Waorani, Shell abandoned their oil drilling efforts before the Elliots came to Ecuador. However, after the Ecuadorian government had consulted with Shell, the government considered sending in military troops to clear the area of the Waorani, in order to entice Shell to return. This concern motivated the missionaries to accelerate their efforts to try to reach the Waorani before the Ecuadorian government would try to intervene.↩

4. Ellen Vaughn’s biography, Becoming Elisabeth Elliot, does address the claim that Jim Elliot’s hesitancy about marriage was due to a repressed homoeroticism, but she simply remarks: “Perhaps if you are a revisionist with a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” ↩

5. The courtship process was further complicated by a disastrous visit made by Elisabeth to Jim’s family in Oregon. Ellen Vaughn expands on Lucy Austen’s explanation as to what happened: During the visit itself to meet Jim’s parents and extended family for the first time, everything seemed to go well. But afterwards, Jim wrote a devastating letter to Elisabeth, describing how his parents and others in the family were less than impressed by Elisabeth, thinking her unsuitable as a potential marriage partner to Jim. Jim’s parents thought of Elisabeth as immature, not very sociable, and lacking the appropriate skills needed to be a missionary. Elisabeth judged her visit to meet Jim’s parents as a “flop.” Nevertheless, Jim sought to engage his parents to rethink their opinion of Elisabeth, but the influence of his parents probably partly explains Jim’s hesitancy about marriage with Elisabeth. See also Valerie Shephard, Devotedly, pp. 108ff.↩

6. Readers should follow the work of Valerie Elliot Shephard, Devotedly: The Personal Letters and Love Story of Jim and Elisabeth Elliot, for more detail and source material regarding Jim and Elisabeth’s courtship. Shephard is the daughter of Jim and Elisabeth Elliot.↩

7. As Ellen Vaughn writes, LIFE magazine was just one of the many American news outlets which covered the story in the mid-1950s. These were the days when missionary work was lauded in popular news media, well before the cynicism of the 1960s took a much dimmer view of overseas missionary work. Elisabeth Elliot proved that she could write under pressure, as during a furlough back to the United States shortly after the spearing tragedy, she spent six weeks in a New York City hotel room writing the first draft of Through Gates of Splendor, to satisfy the demands of her book publisher.↩

8. Steve Saint, son of Nate Saint, one of the murdered missionaries, eventually went to live among the Waorani people. He became friends in particular with Micaye, one of his dad’s killers, who had become a believer in Jesus. The following video is an interview decades later with Steve Saint and Mincaye. Steve Saint wrote a book about his father and the Waorani, The End of the Spear, which eventually was adapted for a movie appearing the American movie theaters in 2006.↩

9. Ellen Vaughn elaborates on Elisabeth’s conflict with SIL and Wycliffe due to differences she had with the SIL/Wycliffe founder, Cam Townsend. Towsend also wanted to reach the Waorani with the Gospel, but in Elisabeth’s view, Townsend’s approach tended towards being more territorial. Rachel Saint was affiliated with SIL/Wycliffe, and she had built a relationship with a Waorani woman, Dayuma, who had escaped the tribe. Rachel Saint was working to learn the Waorani language with this woman, but Townsend threatened to isolate Dayuma from having contact with other missionaries if other missionaries, like Elisabeth Elliot, sought to pioneer outreach to the Waorani independently from SIL/Wycliffe. Townsend had sent Rachel Saint and Dayuma back to the United States for a year to stir up interest in foreign missions to unreached people groups like the Waorani, even landing an appearance on “This is Your Life,” a nationwide popular television show which exposed the work of SIL/Wycliffe to millions of American television viewers. Elisabeth was not enthusiastic about this style of Townsend’s grandstanding. Elisabeth once wrote in her diary, “Who does the man think he is?” Over time, the conflict lessened as both Elisabeth Elliot and Rachel Saint were able to pioneer outreach to the Waorani together, though the interpersonal clashes between the two women proved irreconcilable in the long run.↩

10. Ellen Vaughn gives a generally more positive portrayal of Rachel Saint in her biography of Elisabeth Elliot, while still acknowledging deep conflict between the two missionary women committed to reaching the Waorani people. Vaughn tells the story of how Rachel Saint was drawn to dedicate her life to reaching out to the Waorani people, which balances the picture of Saint portrayed by Lucy Austen. Nevertheless, even Vaughn shows that the unresolved relational conflicts between Rachel and Elisabeth made it extremely difficult for Elisabeth Elliot to stay in Ecuador working with the Waorani.↩

11. No Graven Image is in a sense autobiographical in other ways. Ellen Vaughn elaborates by noting that in the months prior to Jim and Elisabeth’s engagement in Ecuador, Elisabeth has pursued an opportunity to do language work among the Colorado native peoples in Ecuador for several months. She longed to find someone who could help her learn the native language, and found a man who seemed to be the perfect fit to assist her. However, this man, Don Macario, was shot and killed before Elisabeth was able to make much progress. Elisabeth also tells of keeping her language work in a suitcase, which was eventually stolen in Ecuador, thereby losing several months of hard work to make progress in learning the language. This left Elisabeth confused, wondering why God had led her to go to the Colorado peoples to take on this language task, only to see her main contact person killed and her hard work stolen. Did not God want the Colorado people to have the translation of the Scriptures in their native language?↩

12. In Vaughn’s second book, Becoming Elisabeth Elliot, Vaughn notes from Elisabeth’s journals that Ockenga met with Elisabeth Elliot for lunch, but talked down to her almost the entire time, to Elisabeth’s great annoyance. In Elisabeth’s view, Ockenga like many evangelicals in his day was essentially clueless about the trials faced by missionaries on the field, preferring a more romantic picture of what it meant to be a missionary in the post WW2 era.↩

13. Ellen Vaughn recounts that during visit back to the United States while on furlough, Elisabeth traveled to Oregon to visit her deceased husband Jim’s parents. She “chafed at easy answers and pat phrases” with respect to some of the preaching from her father-in-law. In a discussion with her father-in-law about 1 John 3:10, Elisabeth concluded that a person’s deeds are a sufficient test of one’s spiritual state. From that same discussion, she reflected on Joshua 6:18-19, whereby the Israelites entering the Promised Land were to destroy the booty they found, except for the silver and gold, and vessels of bronze and iron, which were to be dedicated to the Lord. This told her that not everything that belonged to “the world” was to be despised. This line of thought helped her appreciate writings for heterodox sources, such as when she read D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Some of Lawrence’s insights into the human condition resonated with her more deeply than some of her conversations with fellow believers in Christ.↩

14. Ellen Vaugh in her second volume, Being Elisabeth Elliot, recalls material found in Elisabeth’s journals of one speaking engagement where a mission agency executive berated her for giving a less than triumphant pitch for encouraging missionary life, so devastating that the critic even questioned Elisabeth Elliot’s salvation, saying that Elisabeth would have to answer to God for what she said during her talk.↩

15. Ellen Vaugh, in her second volume, Being Elisabeth Elliot, writes that her visit to Jerusalem for ten weeks, within a year after the Six-Day War when Israel captured East Jerusalem, with control of the Temple Mount, along with territory as far north and east as the Golan Heights and as far south as the Negev desert, challenged her received view of the Holy Land. She met with Christians, Jews, and Muslims on different sides of the conflict, asking serious questions about whose side the Lord was on. This was quite different from the dispensationalist view she inherited which only saw the conflict as a fulfillment of biblical prophecy in favor of the Jews. Cornell Capa, the LIFE magazine photographer who covered the story of the death of the five missionaries in Ecuador, who befriended Elisabeth Elliot, largely set up the trip for Elisabeth to travel to Israel. However, Capa was ultimately displeased with the book that she wrote, one of the very few rifts that the two of them had with one another. She speculated that Capa had interfered with the first publisher she presented her manuscript to, leading to the rejection of the book. Elisabeth Elliot then gave the manuscript for Furnace of the Lord to another publisher, which was accepted. ↩

What do you think?