Who was ultimately responsible for Jesus’ crucifixion? Theologically, all of us as humans have played a role in the death of Jesus, while believers in Christ mercifully receive its atoning benefits. But historically speaking, was it Pilate or the Jewish leaders who consigned Jesus to die on the cross? This is a thorny question which requires a careful answer.

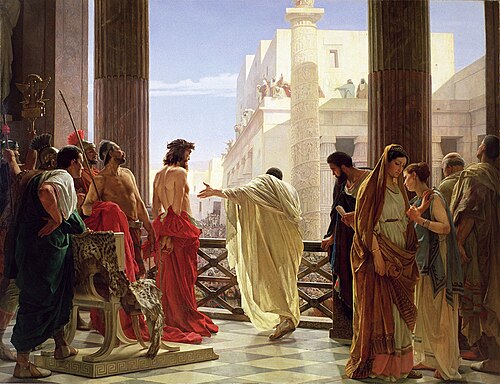

Ecce Homo (“Behold the Man”), Antonio Ciseri’s depiction of Pilate presenting a scourged Jesus to the people of Jerusalem. It took Ciseri twenty years, from 1871 to 1891, to complete the painting (from Wikipedia)

Pilate’s Hands Washing: From Mick Jagger to a Cathedral in Regensburg, Germany

The Rolling Stones lead singer, Mick Jagger, imprinted a passage from the Christian New Testament on the minds of a generation, when in 1968 he first sang “Sympathy For The Devil,” as a personification of Satan:

“And I was ’round when Jesus Christ

Had his moment of doubt and pain

Made (expletive) sure that Pilate

Washed his hands and sealed his fate”

What was the washing of Pilate’s hands all about? In Matthew 27:1-2, the Jewish chief priests and elders judged that Jesus should be put to death, but they sent him to Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea anyway. Later in Matthew 27:24-26 we read of the aftermath of Pilate’s interview with Jesus:

So when Pilate saw that he was gaining nothing, but rather that a riot was beginning, he took water and washed his hands before the crowd, saying, “I am innocent of this man’s blood; see to it yourselves.” And all the people answered, “His blood be on us and on our children!” Then he released for them Barabbas, and having scourged Jesus, delivered him to be crucified.

All four of the Gospels note that Pilate had a role in Jesus’ crucifixion, but there are some differences in how Pilate is portrayed. What is peculiar about this passage in Matthew is that none of the other three Gospels record the incident of Pilate washing his hands. Neither do the other Gospels tell of the specific response of the people, “His blood be on us and on our children!”

Was Matthew putting the blame for Jesus’ crucifixion on the Jews? Or is something else going on here?

On a trip to Europe my wife and I took in 2022, I was stunned to see so much historical evidence of antisemitic sentiment preserved in what was once the very heart of Christendom, central Europe. In Regensburg, Germany stands a great cathedral, where one side looks over the remains of what once was the city’s only Jewish synagogue. Prior to becoming an Anabaptist in the early 16th century, Balthasar Hubmaier, who was then a firebrand medieval priest at that cathedral, preached a pogrom against Regensburg’s Jewish population, leading to the expulsion of Regensburg’s Jews and the destruction of their synagogue. Regensburg’s Jews had been labeled as “Christ-killers,” whereby the blame for Jesus’ death had shifted from Pilate to the Jews, and the label got stuck there.

A memorial to the destroyed old synagogue stands in its place now, overshadowed by the towers of Regensburg’s St. Peter’s Cathedral. On the side of the church is engraved a “Judensau,” an image of several Jews sucking from the teats of a female pig, a disgusting vilification of Judaism. I do not even want to post an image of this on this blog post! Some 48 towns across Germany have “Judensau” engravings on their Christian churches, dating back to medieval times. Why were church authorities so willing to allow such degrading carvings on their cathedrals?

Some have tried to have these Judensau engravings removed. But I am in a sense grateful that they are still around, as it helped to convince me that antisemitism is real, deeply embedded in the psyche of many, and we should leave reminders of the past around in order to educate younger generations.

Walking around the streets of Regensburg, and other European cities, like Prague and Munich, and seeing the evidence of centuries of antisemitic propaganda advertised by those claiming to be Christians was quite a shock to me. How could so many people call themselves Christians and do such repulsive things towards Jewish people?

That question haunted me as I wandered the streets of Regensburg.

When I reviewed two books on Veracity a few years ago, Augustine and the Jews, by Paula Fredriksen (a convert herself from Roman Catholicism to Judaism), and Future Israel: Why Christian Anti-Judaism Must Be Challenged, by Australian evangelical bible scholar, Barry E. Horner, I felt a lot of discomfort reading about the history of antisemitic acts perpetrated by so-called “Christians.” I got another taste of that discomfort in reading When A Jew Rules the World, by Bible prophecy teacher Joel Richardson, showing that some of my heroes in the early church voiced a kind of anti-Jewish sentiment at times in some sermons. But that visit to Europe two years ago convinced me that the history of antisemitism was worse than I had previously thought.

This blog post goes on multiple rabbit trails, but I want to address several issues:

- Answering the charge by critics that the New Testament is antisemitic.

- Thinking about why the Gospel of Matthew portrays Pontius Pilate the way Matthew does.

- Showing how the Gospels use Greco-Roman compositional devices to frame their narratives.

- Comparing modern compositional devices with the way first century literature like the Gospels were written.

- Making the case that a nuanced understanding of biblical inerrancy increases our confidence in the Bible.

- How Christian “Fan Fiction” has shaped the way we have thought about Pontius Pilate down through the ages.

- Christians have been both “Bullies” and “Saints” in church history, and why it is important to wrestle with this.

Christians should be able to share the Gospel with our Jewish friends without stepping on mines filled with anti-Jewish prejudice. Journey with me on this exploration of Christian apologetics through the lens of church history!

Bullies and Saints: An Honest Look at the Good and Evil of Christian History, by John Dickson, explores many of the good contributions of Christianity to the world, while also casting a light on a number of the more unsightly episodes of church history, that as a Christian I would rather forget. Celebrating the goodness of the Gospel’s impact on society while simultaneously acknowledging failures of the church along the way is vitally important, in a day when many in Western culture are skeptical about the value of organized Christianity.

A Brief Look At Anti-Judaism In the Early Church

Such antisemitic sentiment has continued on into the 21st century across the world. Sadly still, such sentiment can be traced back into the early church era, particularly when Christianity became the official religion of the Roman empire under emperor Theodosius. John Dickson, the author of Bullies and Saints: An Honest Look at the Good and Evil of Christian History, shines a bright light on this darkness of Christian antisemitism.

Constantine, who preceded Theodosius as emperor by a few decades, paved the way bringing in Jewish and Christian ideas into his governmental rule. Some of it was indeed for good. For example, according to Dickson, setting aside periods of scheduled rest was relatively unknown in the ancient world. Seven days a week, your average worker in Rome never had a vacation or a periodic day of rest. But Constantine mandated a day off, drawing from the Jewish concept of “the Sabbath.” If you ever wanted to know who gave us the concept of the “weekend” in the Western world, you can thank emperor Constantine.

Thank God, it is Friday, right?… Or just thank emperor Constantine.

Constantine also banned the brutal practice of crucifixion. This was obviously a tip in favor of Christianity.

Yet Constantine’s administration was marked by anti-Jewish sentiment as well. Dickson retells the story told by the 4th century church historian, Eusebius. Constantine had:

‘….banned Jews from owning Christian slaves on the absurd religious grounds that it was improper “that those whom the Saviour had ransomed should be subjected to the yoke of slavery by a people who had slain the prophets and the Lord himself.”’1

Thankfully, there have been those like Saint Augustine of Hippo, who while disagreeing with traditional Judaism theologically, nevertheless championed respect and tolerance for the Jewish communities of his day. Afterall, the Jewish communities over the centuries have preserved the very Old Testament that stands as an integral part of the Christian Bible.

Unfortunately, a passage like Matthew 27:24-26 has been used to justify pogroms against various Jewish communities across church history, labeling Jews as “Christ-killers.” The passage has tended to influence some interpreters to think that Pontius Pilate was somewhat weak in dealing with the demands by Jewish leaders to have Jesus killed. This has led some to wrongly conclude that the Jewish people, or at least the Jewish leaders at the time, were ultimately the ones to blame for Jesus’ death.

However, there are a number of historical problems with this view. Early Christianity scholar Elaine Pagels in her 1995 book, The Origin of Satan (pp.29ff) tells us that Pilate was not as supposedly weak in the face of Jewish opposition as some interpreters have thought. Philo, the great Jewish philosopher of Alexandria, Egypt, and a contemporary of Jesus, describes Pontius Pilate as a man of “inflexible, stubborn, and cruel disposition,” who ruled Judea with “greed, violence, robbery, assault, abusive behavior, frequent executions without trial, and endless savage ferocity.”

Josephus, the primary Jewish historian of that period, writes about several episodes when Pilate could have cared less about the peculiarities of Jewish faith and practice. Pilate’s predecessor recognized that images of the Roman emperor emblazoned on military standards were considered idolatrous by many Jews, so he made sure that the Roman standards in Jerusalem did not display such offensive images. Pilate, on the other hand, deliberately reversed this precedent, parading images of the emperor in Jerusalem to coincide with the Jewish Day of Atonement and the Feast of Tabernacles. After Jewish protests, Pilate finally relented and removed the offensive standards. But Pilate still had a bone to pick with Jewish sensitivities.

All of the Roman governors who ruled Judea were careful not to distribute minted coins bearing idolatrous images and pagan cult symbols in Judea…. except for Pilate. Archaeologists have recovered such coins dated to 29-31 C.E., a time consistent with Jesus’ ministry. Is it then no surprise for Jesus to point out that the image of Caesar was emblazoned on the coins used by Jews to pay taxes to Rome? (Matthew 22:15-22 ESV).

Pilate did not seem to care. If Jews were offended, so what?

Thank Pontius Pilate for the Aqueduct

One of Pilate’s next actions was to build an aqueduct in Jerusalem. As the Monty Python sketch above from their 1979 black satire film, Life of Brian, tells us, Pilate’s aqueduct improved water standards, for sure. But he raided the Jerusalem Temple treasury in order to pay for the project, a sacrilegious act, even according to Roman standards.

When the Jews learned of this, they staged a massive protest against Pilate, larger than the earlier one involving the military standards. Pilate then ordered Roman soldiers to dress in plain clothes and intermingle in the crowd, with weapons hidden under their garments. When Pilate ordered the demonstration to disperse, a number of Jews were killed in the stampede and the melee that followed.

The Gospel of Luke might be referring to this incident in Luke 13:1:

There were some present at that very time who told [Jesus] about the Galileans whose blood Pilate had mingled with their sacrifices.

Pilate’s governorship of Judea proved so controversial, and generated so many complaints, that Pilate had become an embarrassment to the Romans. When Pilate ordered the killing of Samaritans, who were looking for artifacts supposedly left near Mount Gerazim by Moses, that proved the final straw around the year 36 C.E., just a few years after Jesus’ crucifixion. The Roman legate of Syria stripped Pilate of his commission and ordered Pilate to return to Rome to face emperor Tiberias and answer the charges against him. Tiberias died in 37 before Pilate got to Rome, but nevertheless, from then on, the historical record about Pilate goes missing.

Elaine Pagels echoes the report made by Reza Aslan in his Jesus of Nazareth, Zealot (ch. 5), that Pilate crucified thousands of Jews. Assuming that the story of Jews by the thousands being crucified under Pilate is indeed true, it casts serious doubt on the claim that Pilate knuckled under pressure from the Jews to have Jesus killed. By all accounts, Pilate was one mean dude, who despised the Jews and their faith. Having Jesus crucified mattered little to Pilate. He was just one more Jew to add to the list.

Pontius Pilate might have felt right at home in Hitler’s Nazi Germany. To borrow from a rather unfortunate slogan, Pilate might have thought: “The only good Jew is a dead Jew.”

St. Peter’s Cathedral, in Regensburg, Germany. Regensburg was one of the few Central European cities that escaped bombardment during World War II, thus preserving much of its medieval and ancient history. Though a delightful town popular among American tourists, it preserves the memory of a pogrom against Regensburg’s Jewish population, just prior to the start of the Protestant Reformation, with a Judensau, a haunting image carved into the side of this church (too high up and too far away to be seen easily from this photograph I took: October, 2022)

Wrestling With Pontius Pilate in Matthew: Washing His Hands to Seal Jesus’ Fate

So, how does one account for the statement in Matthew 27:24-26 about the washing of his hands, suggesting Pilate’s innocence regarding Jesus’ death?

For starters, the passage still acknowledges that Jesus was delivered by Pilate over to be crucified. Crucifixion was the preferred Roman treatment for capital punishment. This was not so among the Jews. Instead, Leviticus 24:16 specifically describes stoning as the appropriate treatment for blasphemy, the charge laid against Jesus. After all, we know that Stephen was stoned to death for blasphemy (Acts 7). Yet the Gospels mentioned nothing about the possibility of having Jesus’ stoned to death, when he appears before the Jewish high council. For if indeed the Jews were alone primarily responsible for the death of Jesus, it is difficult to conceive that they would have involved Pilate and crucifixion with the matter, unless there was something more going on with the story.

Pilate must have had some kind of interest in Jesus, thinking of him as a trouble-maker. Surely, anyone who was going about proclaiming the “Kingdom of God,” and drawing massive crowds to hear him preach, would have caught the attention of someone like Pilate.

Some new research by Paul Barnett, an Australian and Anglican New Testament scholar, in his recent book The Trials of Jesus: Evidence, Conclusions, and Aftermath, suggests that the Jewish Temple high priest, Caiaphas, had increased his political power in Judea, while Pilate’s position with Rome was on a decline, which could also explain how Caiaphas might have been in a position to manipulate Pilate to have Jesus condemned to crucifixion. Regardless of the reason, Pilate is still “on the hook” for having Jesus crucified.

Furthermore, the idea of washing one’s hands as a gesture of one’s innocence has its roots in Jewish practice, not Roman (Deut 21:6-9; Ps 26:6). Given Pilate’s disgust with the Jews, it is fairly improbable to think that Pilate would have borrowed a Jewish custom like this (unless he wanted to mock his Jewish audience).

Some have therefore concluded that the effort by the Gospels to obfuscate or otherwise deny Pilate’s culpability for Jesus’ death works against the historical reliability of the Gospels. In other words, Pilate was the main reason why Jesus was crucified, and so the Gospels got the history wrong by placing the blame for Jesus’ death on the Jews. However, there is another solution which goes against such needless skepticism.

Considering a Better Approach to Pilate’s Washing of His Hands

New Testament scholar, Michael Licona, in his Jesus, Contradicted, offers a different way to look at the Gospels. In particular, Licona’s proposal might show us how Matthew handles the question about the innocence of Pilate.

As reviewed here on Veracity, Licona argues that the Gospels fit within a particular genre of Greco-Roman writing, that of “bios,” a kind of historical literature which mixes historical reporting with certain compositional devices in order to establish the character of the person or persons being studied. In the case of the Gospels, Jesus was at the center of the story. Therefore, however Pilate was associated with Jesus, the story was crafted to make certain theological points about Jesus’ identity.

A case could be made that Matthew is using a particular compositional device in this passage which fits within this kind of literary genre. Matthew is writing at a time period, a few decades after Jesus’ crucifixion/resurrection, when the Christian movement was expanding under the watchful eye of the Romans. The Gospel message was spreading across the Roman Empire, and the Christians were concerned about possible Roman opposition. It is quite possible that Matthew used the Jewish concept of washing one’s hands to seal Jesus’ fate as a way of signaling to the readers that the Roman government itself was not wholly to blame for the death of Jesus. Matthew was sensitive not to needlessly antagonize the Romans by suggesting that Jesus’ death be pinpointed onto a Roman governor.

It might also be plausible to suggest that the response of the crowds, “His blood be on us and on our children!,” was also a rhetorical way of reinforcing the idea that Christianity was not anti-Roman.

But Is This “Dehistoricizing” the Gospels?

The pushback to such an interpretive proposal is that it might indicate a move to “dehistoricize” the Gospels, which would be harmful to the Gospels’ reliability, or that this otherwise would somehow contradiction the concept of the divine inspiration of Scripture. But this need not be the case.

Here is why: For one thing, there is no doctrine or Christian practice at stake here, if Matthew were to have used such a compositional device to accomplish a rhetorical effect. For example, the use of such rhetoric in this passage has no intention to alter how Christians are to worship and think about our relationship to God and reflecting on the meaning of the cross. Instead, Matthew’s message was intent to not stir up any unnecessary opposition from the Roman authorities. Matthew wanted his readers to understand that the death of Jesus was not about pinning blame on anyone in particular. Rather, the death of Jesus was necessary for accomplishing God’s salvation purposes.

A good example of a compositional device in the Gospels comes from the last words of Jesus uttered on the cross, before he died. In Luke 23:46, we read:

Then Jesus, calling out with a loud voice, said, “Father, into your hands I commit my spirit!” And having said this he breathed his last.

But in John 19:30, we read:

When Jesus had received the sour wine, he said, “It is finished,” and he bowed his head and gave up his spirit.

So what were the last words of Jesus, if you insist that both statements were verbatim from the mouth of Jesus? “Father, into your hands I commit my spirit!” or “It is finished.” Which is it?

Those are your two options. You can not have Jesus say a different sentence at exactly the same time, just a moment before his death. If these statements were both verbatim recollections uttered by Jesus, at least one of our Gospels got the details wrong. One statement had to follow the other. Otherwise, one of those statements, the first one, would not be the last words of Jesus.

However, laying out the options like this introduces a false dichotomy. Instead, one need not insist that both Luke and John were giving us exact verbatim accounts of Jesus’ last words. Does this deny the inerrancy of the Bible? No. Only if your definition of inerrancy is strict would you have a problem. On the other hand, a more flexible view of biblical inerrancy would allow for a surface difference like this.

It is quite plausible to say that Luke’s version is the historical rendering of what Jesus’ last words were: “Father, into your hands I commit my spirit!” In contrast, John’s version might have been the more theological rendering: “It is finished.” For John, he is concerned about the meaning of Christ’s death. Or it could be that John’s version was the more historical, and Luke’s version was more theologically oriented. Either way, both statements in the two Gospel accounts would be true and trustworthy, and therefore inerrant, but only one is historical, in the most strict sense. It is quite plausible that the other Gospel writer used a compositional device to make a theological point.

Compositional Device in Action!!

If you are a bit anxious about how compositional devices work in the Gospels, Michael Licona offers a pretty straightforward example as to how this works. In Mark 1:4-5, that Gospel introduces the reader to the ministry of John the Baptist:

John appeared, baptizing in the wilderness and proclaiming a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins. And all the country of Judea and all Jerusalem were going out to him and were being baptized by him in the river Jordan, confessing their sins.

John the Baptist was causing quite a stir in first century Israel, but the compositional device to pick up on is highlighted: “all the country of Judea and all Jerusalem ” were going out to be baptized by John. Now, is that completely accurate down to the most minute detail? Of course not. Was the entire population of Judea and Jerusalem, including the Sadducees and Pharisees and even Romans all going down to get baptized by John? Of course not!

This is an example of Mark using hyperbole to make a point. Mark is completely accurate in saying that John the Baptist’s movement was very popular among the people, but he is using hyperbole, a compositional device, to drive the point home.

We do this all of the time in contemporary English, everyday speech: “Hey, everybody was at the ball game last night!,” or “You missed that event! The whole town came out to see that celebrity person!,” or “Nobody in their right mind would every pass up a chance to eat ice cream!” Again, we use hyperbolic language all of the time in normal everyday speech, even in the 21st century. So, it should not surprise us when the Gospel writers did something similar.

Let’s Go to the Movies!!

Another example from a classic movie can help to explain this. My wife and I not too long ago watched Robert Redford’s 1976 film about the Washington Post investigation into Watergate, All the President’s Men. Being both a Robert Redford fan, and someone who grew up watching the Congressional investigations into the Watergate scandal on television as a kid, I think this movie is a classic!

At the end of the film, after being chewed out by the Washington Post’s chief editor, the two Post reporters played by Redford and fellow actor Dustin Hoffman are busy typing away on their typewriters in the Post’s news room, while a television plays Nixon’s inauguration of a second term in early 1973, a scene which concludes with typewriters printing out news of the Watergate convictions and Nixon’s resignation, over the following months. Many Nixon top aides were sent to jail, including Chuck Colson, a man who become a Christian while in prison (if you watch the video clip hyperlinked here, just be aware that some of the language is profane).

Now, was that particular memorable scene historically accurate? It depends on what you mean by that. Did the two Post reporters, Woodward and Berstein, spend the day of Nixon’s inauguration typing away at their Washington Post desks, completely ignoring the ceremony? Maybe yes, but most probably not. But did Woodward and Berstein work tirelessly as journalists to investigate Nixon’s coverup of the Watergate burglary investigation? Absolutely, yes.

Likewise, even if Pilate did not actually wash his hands as Matthew tells us, this does not rule out the historical reality that Pilate sentenced Jesus to die a death by crucifixion.

Woodward and Berstein could have been standing on the Washington Mall, watching Nixon’s inauguration for all we know on a cold January day, instead of typing away on their typewriters in their office. But by compressing the events that happened during those first few years Nixon’s second administration, whereby the Watergate story eventually led to Nixons’ resignation, the film director packaged all of that material together into the 5-minute, final scene of the movie, giving a picture of what really happened during the Watergate era. Likewise, Mathew was a literary artist as well, crafting the narrative in order to make the point he was trying to make without sacrificing the substance of history.

Furthermore, the four Gospels are only giving us a summary of what happened when Pilate met with Jesus, and when Pilate displayed Jesus before the crowds. Did this take place over a period of ten minutes, or was it several hours? The text of Scripture does not tell us.

Even if you believe that Matthew reports with technical precision, ‘And all the people answered, “His blood be on us and on our children!”,’ the text does not tell us how this took place. Did the entire crowd give their answer in unison? Did someone shout out one answer, and then someone else another, and then the whole crowd chanted? Again, the text does not tell us. It is quite plausible that Matthew was simply measuring the mood of the crowd, and then he offered his own concise interpretation summarizing what the whole episode meant. If this is the case, then what Matthew did here is consistent with how compositional literary devices functioned in the Greco-Roman bios genre, of which all four Gospels are examples.

When The Spiritual Meaning of the Text Supersedes the Material Meaning

But perhaps the most compelling reason for being open to such a way of reading this passage goes back to the fathers of the early church themselves.

First, it is important to note that the tendency among some in the early church to “blame the Jews” for Jesus’ death was far from being universal. The famous and influential late 4th century church father, John Chrysostom, lived to see the transition of Rome to becoming a “Christian” empire. Nevertheless, when he interpreted this passage, Chrysostom argued that the Jews as a people could not be solely to blame for the death of Jesus, as the great Apostle Paul himself was a Jew as well (Chrysostom, Hom. Matt. 86.2).

We might as well add that Matthew himself, one of Jesus’ twelve apostolic disciples, and the traditional author of this Gospel, was Jewish himself.

Secondly, the late 2nd century / early 3rd century church father, Origen of Alexandria, took a view of the Gospels which some contemporary Christian might find to be very surprising. In Michael Licona’s Jesus Contradicted, we learn that Origen acknowledged a number of surface discrepancies in Gospels. Origen had engaged with critics of Christianity, who did not find the Gospel writings as credible:

[We must, however, set before the reader] that the truth of these accounts lies in the spiritual meanings, [because] if the discrepancy is not solved, [many] dismiss credence in the Gospels as not true, or not written by a divine spirit, or not successfully recorded.2

Surely, it did not escape Origen’s keen eye, as one of the most brilliant scholars in early Christianity, that Matthew’s record of Jesus encounter with Pilate differed slightly from the accounts made by the other three Gospels. Nevertheless, Origen did not accept the idea that such “differences rose to the level of casting doubt on the divine inspiration and reliability of the Gospels” (Licona, p. 8). Origen himself wrote of the Gospel writers, including Matthew:

But I do not condemn, I suppose, the fact that they have also made some minor changes in what happened so far as history is concerned, with a view to the usefulness of the mystical object of [those matters]. Consequently, they have related what happened in [this] place as though it happened in another, or what happened at this time as though at another time, and they have composed what is reported in this manner with a certain degree of distortion. For their intention was to speak the truth spiritually and materially at the same time where that was possible but, where it was not possible in both ways, to prefer the spiritual to the material. The spiritual truth is often preserved in the material falsehood, so to speak.3

Origen was no “liberal” or “progressive” Christian, as these are anachronistic terms which belong the modern period, and not to the 2nd and 3rd centuries when Origen was living. In fairness, it must be noted that Saint Augustine of Hippo, according to Michael Licona, asserted that it was not “allowable to resolve an apparent contradiction in the Scriptures by saying the author was mistaken. For the real solution lay in either a faulty manuscript, a poor translation, or the reader does not understand what is being stated.”4

But even Augustine was not too far from Origen when he acknowledged differences in the Gospels among the four writers:

For indeed there is no other reason why the Evangelists do not relate the same things in the same way, but that we may learn thereby to prefer things to words, not words to things, and to seek for nothing else in the speaker, but for his intention, to convey which only the words are used. For what real difference is there whether it is said, “Blasphemy of the Spirit shall not be forgiven;” or “He that blasphemeth against the Holy Ghost, it shall not be forgiven him.”5

Augustine is thinking about Matthew 12:31 here. A quick look at how various translations render this verse illustrates how different words and phrasings can be use to communicate the same message. Might this also possibly apply with how the other three Gospels more briefly communicate the same message that Matthew 27:24-26 gives us? (compare Matthew 27:24-26, Mark 15:15, Luke 23:24-25, John 19:16).

Even early church father John Chrysostom, in about 390 C.E., agreed that the Gospels have minor historical discrepancies which actually enhance the trustworthiness of the New Testament, instead of undermining that trustworthiness. The differences in the Gospels are:

….a great proof of their truth. For if they accurately agreed in all things, including time, place, and wording, no enemies would believe them but would rather suppose that they came together by some human agreement to write what they did. For such agreement could not stem from sincerity. But as it is now, even the discord in minor matters removes them from all suspicion and clearly defends the character of the writers.6

John Chrysostom was in many ways the “Billy Graham” of the early church era, a powerful and widely respected preacher. He certainly treated the Gospels as being “inerrant,” while still acknowledging minor differences in detail between the various Gospel writers, as part of demonstrating the reliability of the New Testament!

All four Gospels are giving us the “gist” of what happened with Pilate’s actions in delivering Jesus over to be crucified, but all four writers word that encounter differently. The plausibility of this solution to Matthew 27:24-26 is reinforced by the fact that the early church adopted all four Gospels as authoritative texts, despite such differences, instead of merely adopting one Gospel and rejecting the other three, thereby eliminating such differences.

What mattered to all three, Origen, Augustine, and Chrysostom is that the message intended by the Gospel authors mattered more than the exact words used by the authors. This principle does not strictly apply to other genre of literature in the New Testament, such as the letters of Paul, which show literary features more like modern letter writing. But this principle provides a helpful way of navigating difficult passages we find in the Gospels, such as what we find in Matthew 27:24-26.

The Message Intended By Matthew With Pilate’s Washing of His Hands

The theological message that all of the Gospel writers, specifically including Matthew, have in mind concerning the “trial of Jesus” episode with the Jewish council followed by the appearance before Pilate still applies. If I were there in Jerusalem in the first century, whether acting as a Jew or as Roman, as a participant in Jesus’ trial or as an observer, I would have probably done the same thing. I would have likely found some reason to have Jesus’ crucified, or at least approved of it, not knowing the full implications of what Jesus’ mission was all about. Jesus preached a message of truth, a message that would have offended both Jew and Roman alike. Jesus was an “equal opportunity” offender, as all of have sinned and fallen short of God’s glory. There is no need to try to pin the blame for Jesus’ death on any particular party, as all of us humans as rebellious sinners have had our hearts hardened against the things of God.

Even if one is not fully convinced by the case I have made here, it could also be argued that Matthew’s statement recording that: ‘all the people answered, “His blood be on us and on our children!,”’ should be take more straight-forwardly. For if the Jewish people condemning Jesus are taking responsibility, and sharing that responsibility with specifically that next generation of children, and nothing further, then this would fit in very well with Jesus’ prophecy that the Temple would be destroyed within the lifetime of at least some of Jesus’ disciples. Matthew’s statement could even be restricted further in that the “all the people” could specifically mean all the people of Jerusalem who came out to condemn Jesus, as opposed to a blanket reference to all Jews. As this event actually took place in A.D. 70, this statement would actually be more about a fulfillment of prophecy, as opposed to some general condemnation of all Jews in all generations going forward into perpetuity.7

Nevertheless, God in his abundance of mercy and grace, has taken what man meant for evil and turned it into good. Jesus was not ultimately a victim of human injustice, whether that be Jewish or Roman. Rather, it was through the death and subsequent resurrection of Jesus that we as fallen sinners can be saved, and therefore reconciled to God. The New Testament is quite explicit in linking the death of Jesus with human sin more generally, and not blaming any particular person or people group (Romans 5:8-9, 1 Timothy 1:15). Without Jesus’ death on that cross, we might still be under condemnation of our own sin. Instead, it is through the death of Jesus that we ironically have the opportunity to find eternal life, the gift that God has given to all of those who believe and trust in Jesus.

If anything, such a reading of this passage helps to better explain why various interpreters in later generations in the church misused this passage in an antisemitic way. Think back to the Judensau engravings I mentioned earlier, found embedded on the walls of medieval churches across Central Europe.

Matthew wanted to portray the Roman government as innocent in being primarily responsible for the death of Jesus. However, once Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire, the original rhetorical message that Matthew was trying to send became lost and muddled. Pilate no longer would have symbolized the power of a pagan Rome, as now, Rome was effectively Christian!

The downside of this is that the language of Jesus’ blood being symbolically left on the Jews and their children still remained. As the Christians gradually rose to become ascendant in Roman culture, the Jews who did not accept Jesus as their Messiah were subsequently marginalized. Matthew 27:24-26 was then effectively weaponized by certain readers of Matthew’s Gospel to mistreat the Jews.

Furthermore, a good alternative case can be made that Matthew’s statement from Jerusalem’s Jews gathered before Pilate about the blood of Jesus was meant to show that Jesus’ death was a fulfillment of Old Testament prophecy (see Jeremiah 26:15), and not some blanket condemnation of the Jews for all generations following the era of Jesus. Jeremiah’s prophecy was made several hundred years prior to Jesus’ appearance before Pilate:

Only know for certain that if you put me to death, you will bring innocent blood upon yourselves and upon this city and its inhabitants, for in truth the Lord sent me to you to speak all these words in your ears (Jeremiah 26:15 ESV).

This would have very likely rung true for those who witnessed the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 A.D. But as Christian readers towards the end of the early church period began to lose touch with the world of the Old Testament, many of these Christian readers would not have recognized these connections to earlier prophecy.

One can still accept the role that Pilate played in the death of Jesus, alongside the role that the Jewish chief priests and elders did as well, and in their influence over the Jewish crowds. Both parties sought to have Jesus killed, just as any of us would have done, had we been there to participate in the madness. Thankfully, what was once regarded a tragic death of an innocent person has now been overturned to become the very event in history that has made salvation possible. It is a message which continues to bring many into a saving relationship with Jesus, whether they be the descendants of Jews or Romans alike.

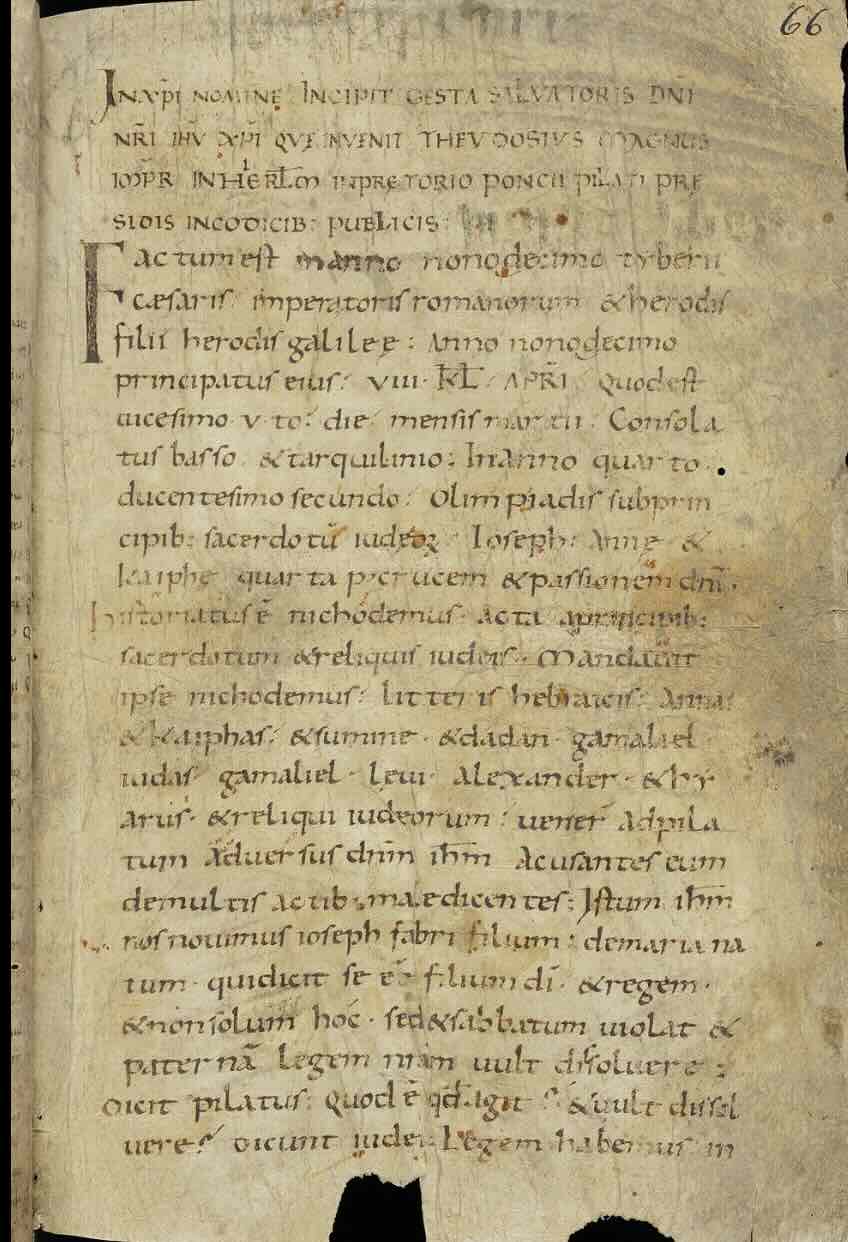

A 9th or 10th century copy of the Gospel of Nicodemus, sometimes called the Acts of Pilate, in Latin.

Christian “Fan Fiction” About Pontius Pilate

If you think I am making too much about this episode of Jesus before Pilate, and its influence on antisemitism, then I urge you to think again. In Simon Gathercole’s book The Apocryphal Gospels, Gathercole tells the story of a 5th century supposed “Gospel,” the Gospel of Nicodemus. This text became a kind of “fan fiction” for some Christians during the medieval era. This text has also gone by the name of the Acts of Pilate, which includes a description of Jesus’ appearance before Pilate.

When Jesus is brought in before Pilate, something interesting happens. As Gathercole translates the story (Gathercole, p. 217):

When Jesus came in, accompanied by the standard-bearers holding the ensigns, the emblems of the emperor on them bowed down and worshipped Jesus. When the Jews saw how the standards were bowing down and worshipping Jesus, they railed against the standard-bearers.

Pilate then addressed the Jews. ‘Aren’t you struck by how the emblems of the emperor are bowing down and worshipping Jesus?’ he said.

‘We saw that it was the standard-bearers that bowed down and worshipped him,’ they said.

The governor called to the standard-bearers. ‘Why did you do this?’ he asked them.

‘We are Greeks, and temple-servants,’ they answered. ‘How could we worship him? When we were holding the emblems, they bowed down and worshipped him all by themselves.’

Pilate addressed the synagogue leaders and the elders of the people. ‘Choose for yourselves some mighty, strong men, to hold the standards,’ he said. ‘Then we will see if the emblems bow down by themselves.’

Pilate then urged that the emblems on the Roman standards be kept up standing in honor of Caesar, and charged the standard bearers to do their job, upon pain of death. Nevertheless, Jesus was brought into the room again, and yet again, the Roman emblems bowed down to Jesus, despite the Jewish efforts to hold the standards upright.

When Pilate saw this, he was terrified and tried to stand up from his judgement seat.

The point of the story by the author of the Acts of Pilate is to paint Pilate in a sympathetic light. Yes, Pilate did order Jesus’ execution, but he did so with grave concern. He was in awe of Jesus, and knew of his innocence. But this sympathetic portrayal of Pilate came at the expense of the Jews who were there condemning Jesus.

An extra-biblical account, hundreds of years after the event, of Roman standards miraculously bowing down to Jesus, while in Pontius Pilate’s presence, is highly suspicious, so its historical accuracy is very, very weak. But as a kind of propaganda, it proved to be very effective during the medieval period.

There is even another story from the medieval period that seeks to exonerate Pilate. Pilate was recalled to Rome eventually by the emperor Tiberias. This much is true. But this particular story goes on in saying that Pilate had to give a report about his treatment of Jesus to the emperor. The Roman emperor was pretty upset by Pilate’s actions in Judea, believing Pilate to have unnecessarily aggravated the Jewish population, and had Pilate executed. But before Pilate was killed, the story goes on that he converted to Christianity, realizing Jesus really was the promised Jewish Messiah, contrary to what the unbelieving Jews were claiming. Similar stories have been told and retold across the centuries.

These type of stories were so popular that some Christians in Egypt would name their baby boys after Pilate, a practice that continued on into the 18th century.

Did Pilate really convert to Christianity? Mmmm…. maybe, or maybe not.

Some still claimed that Pilate was primarily responsible for killing Jesus, but popularity for putting the blame on the Jews eventually overtook the public imagination. It should be pretty easy to see how “fan fiction” like this eventually spilled over into derision towards the Jewish communities in later church history, blaming the Jews for “killing Jesus” while Pilate gets a kind of pass for his actions. Hitler and his cronies played into such rhetoric to advance their Nazi agenda.

Some scholars are skeptical that Jesus even appeared before Pilate at all. After all, why would Pilate really care about a theological feud among the Jews? Well, we really do not need to go that far. Such skepticism is not warranted. For if indeed death by crucifixion explains the fate of Jesus, and this is widely accepted (except in Islam), it only makes sense for a Roman official, like Pilate, to have interrogated Jesus and issue the directive to employ a Roman method for execution, a method which the Jews generally despised.

Given the evidence, it would appear that Pontius Pilate’s role in the crucifixion of Jesus can not be minimized. The very fact that the Nicene Creed, the most well-known and widely accepted summary of Christian faith, explicitly names Pilate as the one who personally authorized the death of Jesus, can not be avoided. To pin the blame primarily on the Jews, thus exonerating Pilate’s pivotal role, is a difficult argument to sustain.

Christians Have Been Both Bullies and Saints

This blog post was inspired by reading John Dickson’s excellent and sobering Bullies and Saints: An Honest Look at the Good and Evil of Christian History, which details examples of Christians behaving badly across 2,000 years of church history. It is important to acknowledge instances where the church, or a least certain Christians at various times, got things terribly wrong. We need to own up to those failures, and take it on the chin, as in the case of antisemitism in the church. Some try to make weak excuses for such behavior, for which critical nonbelievers can see right through.

At the same time, some critics of the faith will try to place blame on the New Testament itself for the evils of church history. I disagree with that assessment. The problem is not the New Testament itself but rather the failure of those who have misinterpreted the Bible over the centuries. A more adequate understanding of how literary genre in the Bible functions can help us to better honor the sacredness of Holy Scripture.

If you want to learn more about how the literary genre of the New Testament Gospels helps us to better make sense of differences between the Gospels, and we might have better, more robust view of the inspiration and inerrancy of Scripture, please consider this Veracity review of Michael Licona‘s Jesus, Contradicted: Why the Gospels Tell the Same Story Differently.

Notes:

UPDATE: November 9. Corrected some information about the Acts of Pilate, and added a photograph of a medieval copy of the document.

1. John Dickson, Bullies and Saints, pp. 75-76. Dickson chronicles other examples of antisemitism in church history, particularly in the medieval period, on pages 222ff.↩

2. As quoted by Licona, Jesus Contradicted, p.8. Origen, Commentary on the Gospel according to John, Books 1– 10 , trans. Ronald E. Heine, The Fathers of the Church, vol. 80 (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1989), 256, par. 10.↩

3. As quoted by Licona, Jesus Contradicted, p.8: this from Origen, Commentary on the Gospel according to John, Books 1– 10 , 80:259, book 10, par. 19– 20 (Heine). For the Greek text, see Origen, Origenous ta euriskomena panta , 4.74– 75, p. 313. The Greek term translated “falsehood” in this text is pseudeiōs . A similar statement was made in the fourth century by John Chrysostom ( Hom. Matt. [ Homilies on Matthew ] 1.6)….. Licona also references Origen’s analysis of Gospel differences, describing the number of differences in the Gospels as “dizzying”: Origen, Commentary on the Gospel according to John, Books 1– 10 , 80:257, book 10, par. 14 (Heine). For the Greek text, see Origen, Origenous ta euriskomena panta = Origenis opera omnia, patrologiae cursus completus, series graeca , t. 13 (Paris: Migne, 1862). Those interested may access this Greek and Latin text at https://bit.ly/2o9mlRS and scroll to page 312, 2.68. The Greek term translated “dizzying” is skotodiniasas.↩

4. Per Licona, Jesus Contradicted,, p. 8-9, from Augustine, Faust. 11.5, and closely related to Letter to Jerome by Augustine (Ep. 82.1.3)↩

5. Per Licona’s footnote, Jesus Contradicted, p. 9: Augustine, Serm. 21.13 (NPNF 1 ). Augustine of Hippo, “Sermons on Selected Lessons of the New Testament,” in Saint Augustine: Sermon on the Mount, Harmony of the Gospels, Homilies on the Gospels , ed. Philip Schaff, trans. R. G. MacMullen, A Select Library of the Nicene and Post- Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church , 1st series, vol. 6 (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1888), 322. See also Origen, Commentary on the Gospel according to John, Books 1– 10 , 80:259, book 10, par. 19– 20 (Heine).↩

6. Per Licona’s footnote, Jesus Contradicted, p. 10: Chrysostom, Hom. Matt. 1.6, PG 57.16.↩

7. See essay, “The Editor’s Preface to the First Edition,” by Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Avi Brettler in The Jewish Annotated New Testament, p. xiii. ↩

November 16th, 2024 at 7:07 pm

This female journalist has 222K followers on X/Twitter. If you do not think antisemitism in the church is real, go read this tweet yourself:

https://x.com/KimIversenShow/status/1852364903857688862

LikeLike

November 17th, 2024 at 8:56 am

Not too long after I published this blog post, philosopher Lydia McGrew suggests a different way of approaching the last words of Jesus, spoken on the cross, which differs from how New Testament scholar Michael Licona approaches the issue. As noted in my post, Licona’s approach suggests that either Luke or John is using a compositional device to compress Jesus’ sayings on the cross into a simpler reading in order to convey a theological message, consistent with how the particular Gospel was inspired; whereas the other Gospel writer is giving us the actual last words of Jesus uttered before his death.

In the cases of Matthew and Mark, both of these Gospels simply say that Jesus uttered a loud cry, and then breathed his last, without telling us exactly what Jesus said.

McGrew states that we need not appeal to a compositional device to explain the discrepancy between the two Gospels. For McGrew, Luke and John can be harmonized in the sense that Luke’s source may have stood further away from Jesus on the cross, unable to hear any whispered words, whereas the John was with Mary, Jesus’ mother, at the foot of the cross, where he could hear everything.

For McGrew, this explains why Luke records Jesus’ last words as “Father, into your hands I commit my Spirit,” whereas John records Jesus’ saying, “It is finished.” In McGrew’s reconstruction, Jesus says both. First, Jesus utters Luke’s recorded words loudly, and then John whispered “It is finished” as he was exhaling his last breath.

Admittedly, this reconstruction is possible. However, it does not explain why John chose not to record Luke’s source, “Father, into your hands I commit my Spirit,” even though he is standing just a few feet from the cross. Could he not hear the same thing that Luke recorded?

A better explanation is to say that Luke and John were writing their inspired Gospels with different purposes in mind, using compositional devices common to first century Greco-Roman biography, what scholars today call “bios,” to effectively communicate the message that Jesus was articulating, which does not demand the kind of technical precision which McGrew suggests is at play here.

The Gospels are ancient biographies. They are not legal depositions to be used in court settings.

What troubles me about McGrew’s approach is that her definition of biblical inerrancy is very strict. It is so strict that she, in fact, denies biblical inerrancy, suggesting that there are certain passages in Scripture that do genuinely contradict one another. I take a different view, in that with a more flexible view of inerrancy, which takes into account literary features like Greco-Roman composition devices, you have a Bible which can be fully trusted as inerrant, without having to demand that each and every precise technical detail be harmonized with one another, as you might look for if the Gospels were some kind of a legal deposition to be used in a court of law. In other words, I believe in the inerrancy of Scripture, but Lydia McGrew does not.

LikeLike

November 28th, 2024 at 9:17 am

N.T. Wright, in Jesus and Victory of God, (p. 546), takes the position that the Matthew passage about “his blood be on us, and on our children” is indeed a reference to the fall of Jerusalem in the year 70 A.D.

LikeLike

March 8th, 2025 at 12:14 pm

Dr. Paul Maier, a great evangelical bible scholar, died on February 27, 2025. In this interview, he talks about what we know about the historical Pontius Pilate:

LikeLike