The Book of Revelation is not only the last book in the Bible. It was also one of the last books to have gained full acceptance into the New Testament canon of Scripture. Interestingly, controversy about Revelation arose starting around the 3rd century, despite its general acceptance in the 2nd century. Hesitancy about the book was largely due to various difficulties readers had in trying to understand what the author, named John, was trying to teach.

Back when I was in high school, I managed to read the entire New Testament cover-to-cover over several days…. EXCEPT for the Book of Revelation.

Frankly, I could not make sense of it. I gave up on it, until I picked it back up again in briefly in college, and more intensely years later in seminary. Over the years since then, I have learned that I was not alone with my initial confusion about the book.

Even the great conservative stalwart Protestant of the 16th century, Martin Luther, had his own doubts about the very inspiration of the Book of Revelation, as Bart Ehrman tells us, saying that Luther “can in nothing detect that it [Revelation] was provided by the Holy Spirit” (Armageddon, Ehrman, p. 32). Nevertheless, Luther submitted to the collective mind of the early church as accepting Revelation as part of canonical Scripture, translating it into his German version of the New Testament, though he did place the book in his New Testament translation in an appendix and not the main body of the translation (Ehrman, p. 31). Despite Luther’s personal skepticism, traditional Lutherans today still accept the Book of Revelation as inspired Word of God, as do all historically orthodox Christians.

The late Protestant Bible teacher, R.C. Sproul, once said that the canon of Scripture is a fallible list of infallible books. My Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox friends might push back a little on this, and Sproul’s statement can sound a little odd even to Protestants. Nevertheless, all historically orthodox Christians affirm the Book of Revelation as infallible…. though difficult to interpret when it comes to some of the nuts and bolts of the text.

Revelation can be a hard book to understand. But why?

In the first part of this book review of Armageddon: What the Bible Really Says About the End, some consideration was made as to the violent imagery we find in the book, analyzing the type of literature the book is (apocalyptic), and concluding with a look into the controversy regarding the millennium. While every biblical scholar knows that Revelation contains a great deal of symbolism, much of the controversies in interpreting the book come down to (a) how much is symbolism being used, and (2) when you do find symbolic language, what do these symbols mean?

In this second and last part of this review, some of the other difficulties are explored, along with an analysis of what Bart Ehrman thinks the book is really about. I then hope to show why Ehrman’s solution is itself problematic.

Armageddon: What the Bible Really Says about the End, by Bart Ehrman.

Dating the Book of Revelation: Perhaps the Most Popular Evangelical View is Not the Most Correct One

There are a number of times where Bart Ehrman makes certain arguments from which even the most conservative of Christians would do well to learn from. For example, for centuries it has been believed that the Book of Revelation was written as late as the early 90’s of the first century, during the reign of emperor Domitian. It has been believed that under Domitian’s rule (81-96 CE) a great massive persecution of Christians would explain the situation as to why Revelation had been written.

The historical context for the book is important, mainly in that so many Christians tend to think that the book is primarily about events that were prophesied to happen some 2,000 years off into the future. While this does not necessarily rule out at least some future foretelling, which most conservative commentators recognize, it would only have made sense to the original audience if the author was trying to connect at least some, if not a majority of the details, to events taking place in the first century.

The Book of Revelation strongly indicates that the Christians of the day were under threat of persecution, and so John wrote this book in order to encourage the believers to stay faithful to Christ in face of such opposition to the faith. Revelation 12:13 is just one instance where the theme of persecution is mentioned:

And when the dragon saw that he had been thrown down to the earth, he pursued the woman who had given birth to the male child.

Over the centuries, Christians have read Revelation as a source of strength in times of great hardship.

However, as Ehrman notes, many scholars now question whether or not a great persecution happened under Domitian’s rule at all. We lack sufficient evidence from the historical record to indicate such a state sanctioned persecution happened in the late first century, except for some reports of exiles of certain Christian leaders. There could easily have been local police actions against Christians, as there certainly was by the early 2nd century, just a decade or two later. But there was nothing terribly widespread to account for the writing of such a vigorous document as the Book of Revelation, according to the evidence we currently possess. While this newer scholarly view could be falsified by the possible unearthing of even newer data demonstrating widespread persecution under Domitian, the growing consensus of historians today suggests that very few Christians were martyred under Domitian’s reign, if any (See my review of Wolfram Kinzig’s Christian Persecution in Antiquity for more detail).

Instead, a better candidate for the dating of Revelation would be under the reign of Emperor Nero, around 64 CE, in response to the accusation that Christians had instigated the burning of the city of Rome. Nero was known to have used Christians as torches, as a result of casting blame on them for the fire in Rome.

Granted, the persecution under Nero was focused primarily within the city of Rome itself, and would not have posed an immediate threat to the churches in Asia Minor (modern day Turkey), where much of the Book of Revelation was situated. However, Nero’s efforts to punish Christians would have sent shockwaves throughout the Roman empire, as the Christian movement had not faced such violent opposition up to this point in time. This might have been more than enough to terrify the believers in Asia Minor, to justify the writing and circulation of Revelation across this growing number of churches, particularly in the Christian East.

Internal evidence in Revelation itself suggests that the book was written in the period of Nero, within the decade prior to the destruction of the Jerusalem temple of 70 A.D. Revelation 11:1-2 records that the vision to John told him to measure the physical dimensions of the temple in Jerusalem. It would be difficult to imagine John receiving such instruction if the Revelation was written after 70 A.D., when the Jerusalem temple no longer physically existed.

Nevertheless, many Christians still hold onto the 90’s dating for Revelation, so one needs to be careful not to be too dogmatic concerning the date. It is possible that Revelation was written after Nero died, with the author thinking that another Nero might loom along the horizon.

Interestingly, Ehrman accepts the later 90’s dating of Revelation. But because he accepts the scholarly consensus that there was no massive persecution of Christians under Domitian, Ehrman suggests that John of Patmos, the author, likely exaggerated the persecution situation, or that John had other motives for writing the book.

Nero’s Torches , 1876, by

Henryk Siemiradzki (1843–1902). Nero used Christians as torches in Rome, in the last days of Paul.

Bart Ehrman’s Take on the Book of Revelation’s Message: Fundamentalist Literalism Now Skeptical Literalism

In particular, Armageddon argues that Revelation is about pronouncing judgment against the opulence and great wealth of Rome. Ehrman’s argument culminates with a rather shocking view of the millennium.

Ehrman follows the sentimentality of D.H. Lawrence, the author of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, in saying that John of Patmos instead believed that the Christians should be the ones who possessed such great wealth, and not the pagans. In other words, Ehrman argues that the Book of Revelation is ultimately making a case for a great wealth transfer: That God will take the riches from the Roman pagans and give it over to the poor, marginalized Christians, so that they might become the great rulers instead.

In this scenario, Jesus is envisioned to make his final return to earth, prior to the 1,000 year millennium. During this 1,000 year period, Jesus will strip away the wealth from the pagans and hand it over to the Christians, while Jesus rules from Jerusalem. The Christian martyrs, killed by their persecutors in their previous earthly life, have been raised near the beginning of this millennial reign. Onwards, these persecuted martyrs have the opportunity to “pay back” their oppressors with vengeance (see again Revelation 20:4, but also Revelation 6:9-10 ESV).

In other words, in Bart Ehrman’s interpretation, these glorified saints and martyrs in the millennium will have free reign to rule over the unglorified non-believers who killed or otherwise persecuted them, prior to the return of Christ. In the millennium, the tables are now turned. The once persecuted now exact violent retribution on those who inflicted persecution.

In contrast, most versions of premillennialism today, of which I am familiar, do either one of three things, or some combination of the following: First, some interpreters view the resurrection which happens at the start of the millennium to include not only the slain martyrs (Revelation 20:4), but a larger group of raised Christian believers who will co-reign with Christ in the millennial kingdom. This interpretation undercuts much of Ehrman’s proposal, but this interpretation is disputed.

Secondly, some interpreters simply ignore the language regarding vengeance and wealth, and do not comment as to exactly how Christ and the glorified saintly martyrs will rule the nations. They simply state that Christ and these raised saints will rule the world, and then leave it that.

Thirdly, various interpreters will spiritualize, or otherwise reinterpret the language of vengeance and wealth to signify that the rule of Christ accompanied by the glorified saintly martyrs will be marked by righteousness and equity (Isaiah 11:4; Psalm 98:9). Many of those remaining unglorified non-believers, among the nations of the world, will be eventually brought into fellowship with God through conversion to following Christ (Zechariah 8:13-23). It is only at the end of this millennial age will Satan be released to deceive the nations, thus causing a great falling away from the faith, which ultimately will end with the defeat of God’s enemies, along with Satan himself (Revelation 20:7-10).

Ehrman’s extreme view of the millennium will probably shock most Christian premillennialists. Ehrman’s extreme version of a “premillennial” view of the millennium comes close to mirroring what would eventually become the Muslim jihadist view of heaven, whereby those jihadists who die in battle against “non-believers” would be granted an afterlife reward filled with sensual delights to fill unrestrained expansive appetites. In this “glorified” state, the jihadist enjoys the gardens of paradise while the non-believer will be sent to hell by Allah.

Ehrman’s thesis is intriguing at one level. However, at another level, this is a rather crass understanding at odds with any consensus handed down through the ages in historical orthodox Christianity. For if Ehrman is correct, it is difficult to believe that the Book of Revelation would have been accepted into the New Testament canon.

True, there were those like the late 1st century and early 2nd century church father, Papias of Heirapolis, who held to something similar to what today is known as “premillennialism.” Some other later church fathers, like Irenaeus, were sympathetic to Papias, but probably not in the extreme way portrayed by Bart Ehrman. At the same time, other Christians, like the great 4th century church historian, Eusebius, rejected the view of Papias as an absurdity, while still affirming Revelation as part of the Christian New Testament.

Eusebius’ statement from his Ecclesiastical History, (3.39, 12), written in the era of Constantine in the 4th century, concerning Papias is worth quoting:

To these belong [Papias’] statement that there will be a period of some thousand years after the resurrection of the dead, and that the kingdom of Christ will be set up in material form on this very earth. I suppose he got these ideas through a misunderstanding of the apostolic accounts, not perceiving that the things said by them were spoken mystically in figures.

Even though Bart Ehrman presents an interesting argument I had not considered before, his solution comes across as being overly materialistic, hyper-literal, and even cynical. Bart Ehrman’s reading is probably way more extreme than the view of that Papias held, though we lack the primary sources from Papias that might tell us exactly what he thought. Even if Papias’ view approximated Ehrman’s, it would appear that Eusebius was well within the boundaries of orthodox opinion to call such an interpretation a “misunderstanding.”

The impression given is that Bart Ehrman has became so enamored with D. H. Lawrence’s perspective on Revelation that it has colored Ehrman’s reading of the text too much. Though recognized as one of the great novelists of the early 20th century, Lawrence was a proponent of the sexual revolution, Lawrence’s relationship with the Christian faith was strained at best. The temptation to misread Revelation in such a blunt manner partly explains why a number of Christians in the early church were hesitant about accepting Revelation into the New Testament canon of Scripture. No wonder why Augustine had second thoughts about his earlier view of a purely 1,000 year millennial reign of Christ following Christ’s return.

The Early Church Witness for Identifying the “666” Figure as Representing Nero

Much resistance to considering a date in the 60’s for the Book of Revelation among conservative Christians seems to be based on clinging to evidence which we do not currently have as opposed to simply standing more modestly on evidence we already have. I am inclined to accept the 60’s date myself, because of the existing evidence for Nero’s persecution, as opposed to elusive and controversial claims of persecution under Domitian, insisting on evidence we do not fully possess now but which might turn up at a later time. In other words, a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.

Ehrman also describes the view of a 3rd century Christian author, Victorinus, who believed that the number of the beast in Revelation, the (in)famous “666” is none other than Emperor Nero. In addition, the “Babylon” of Revelation is the Roman Empire, according to Victorinus, thus reinforcing the connection with Nero. Furthermore, Victorinus considered the catastrophic cycle of events described in Revelation, like the seals, trumpets and bowls, to be deliberately repetitive descriptions of the same event of judgment, as opposed to a chronological sequence to be played out in a series of “end times” events. Victorinus’ interpretation does not mesh well with a purely futurist reading of Revelation (Ehrman, p. 55).

Nevertheless, there are many Christians today who reject the Nero identity and opt for the “666” figure to be associated with some current public figure. Some might think Russian President Vladmir Putin, or one of the American Presidential candidates, either Kamala Harris or Donald Trump, fit the bill. You can pretty much take your pick, as the associations people conjure up are almost endless (Some of Ehrman’s material on Revelation in Armageddon, like the “666” meaning, overlaps material found in his Heaven and Hell: see my Veracity review).

Perhaps the identification of Nero with the number of the beast is a type which anticipates a future antichrist figure. Perhaps the author of Revelation had Domitian in mind as that future antichrist figure. Perhaps more generally, God’s message in Revelation is to point out that in each and every generation there is some antichrist at work, signs of corruption and abuse of power in social, economic, and political structures that Christians need to call out as such. Given the fact that Nero’s maniacal treatment of Christians has not been unique in church history, it is understandable why interest in a future antichrist can capture the imagination of Christians still today. The Book of Revelation continues to fascinate, comfort, and puzzle Christians today, just as it did in the early church era, in hopes of trying to make sense of the times in which we live.

But we should be wary about attempts to pinpoint the identity of a future antichrist, or any other image in Revelation, with exactness. During the height of the COVID epidemic, I kept hearing a variety of claims that people like Bill Gates or Anthony Fauci were “the antichrist,” as though one of these persons is now finally the antichrist to emerge in human history. Fast forward a few years later and no one seems to be terribly interested in naming such persons as “the antichrist” anymore.

Ehrman’s Critique of One Popular View of the Book of Revelation… But Not the Only View

This review does not do justice to the full treatment of Bart Ehrman’s Armageddon. Much more could be said about Ehrman’s treatment of the history of interpretation of the Book of Revelation, a topic rarely addressed in evangelical church settings, in my experience. The predictive chronology of the 12th century interpreter Joachim of Fiore is quite fascinating, as is the history of when British Protestant Christians became very interested in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, with the idea that the Jewish people will return to the Holy Land, reestablishing a presence there as part of God’s prophetic program. Though interest in prophecy fulfillment national Israel in the 21st century has waned somewhat, such expectations were a major part of American evangelical theological reflection in the 20th century.

I would refer readers to Nick Peters’ more interactive review of the book for more detail (parts #1, #2, #3, #4, #5, #6). If there was one pet peeve I have is that Nick’s review is only one of the very few treatments of Armageddon I have come across from an evangelical Christian perspective. Why more scholars do not write more reviews of Ehrman’s books puzzles me, considering just how popular Bart Ehrman’s books, blogs, and podcasts are in the secular media.

But Nick’s closing observation echoes my primary concern about Bart Ehrman’s Armageddon, despite the learned scholarship Ehrman clearly has on the subject. Ehrman seeks to take down populist readings of Revelation that tend to permeate churches that lack careful attention to informed biblical scholarship. Ehrman puts it like this, and he is right on this point:

“The majority of people who read the book of Revelation never ask about its historical context and literary genre, even though they know (at least implicitly) that these things radically affect a text’s meaning. When it comes to this book in particular, that is a terrible mistake. Making the mistake may not be the end of the world, but it may make you think it is the end of the world” (Ehrman, Armageddon, p. 97).

In Armageddon, Ehrman primarily interacts with the more popular viewpoints, which focus on prophetic events in the future. Granted, Armageddon is tailored towards a popular audience, but the somewhat narrow scope that Ehrman takes in commenting on what “evangelical Christians” believe about Revelation is quite evident. A glance at some other book reviews show that a lot of readers in Ehrman’s intended audience are fans of Ehrman’s previous books, who look to Ehrman as a kind of guide to help them through their deconstruction through or deconversion experience from Christianity.

In Armageddon, the focus of Ehrman’s critique is on the dispensationalist mindset of the Hal Lindsay phenomenon of the 1970s and 1980s. Lindsay’s dispensationalism was made famous by his best seller, The Late Great Planet Earth. While Hal Lindsey is still actively promoting his “biblical prophecy perspective,” I rarely bump into other evangelical Christians today who pay any attention to him. Most people know about this perspective from the “Left Behind” series of books and movies.

Ehrman does discuss Augustine’s influential views on the millennium, the origin of the Seventh Day Adventists in the 1840s, and the truly bizarre tragedy of David Koresh and the Branch Davidians disaster in Waco, Texas in 1993. However, Ehrman seems largely unaware of a partial preterist approach to Revelation, which argues that the book is more about the past and the situation in the first century, and less about events far into the future.

A Couple of Other Resources for Studying Revelation

As an aside, those evangelicals who are wary of reading Ehrman will find that Steve Gregg’s Revelation: Four Views, Revised & Updated, A Parallel Commentary is a suitable alternative for studying different historically orthodox interpretations of Revelation. Gregg does a good job of presenting these different views fairly and even-handedly, including the one which Ehrman focuses on criticizing almost exclusively in Armageddon. I regularly consult Gregg to get a balanced approach to the Book of Revelation (See this Veracity review of Gregg’s book, and a sampling of how Christians have interpreted the “144,000,” an enigmatic feature of the Book of Revelation ).

If you like audio podcasts, I would also recommend Dr. Michael Heiser’s deep-dive into the usage of the Old Testament in the Book of Revelation, from his Naked Bible Podcast. Revelation just makes more sense once you see how the author ties in Old Testament themes throughout the book. I have just started listening to it on YouTube, and it is great!

A Secularized Historical-Critical Method of Reading the Bible Strips Away the Unity of the Whole Text of Scripture

Christians who hold views similar to Hal Lindsay’s, which suggests that a “rapture” of the church will happen as a prelude to a coming seven-year tribulation of those who remain after the rapture, will be deeply frustrated by Ehrman’s book. Ehrman’s skepticism about the “pre-trib” rapture of the church is driven partly by the historical method he adopts in order to interpret Revelation. But his particular historical method is taken to an extreme.

As in Ehrman’s other books, Ehrman largely eschews harmonization of texts which have tension with one another, or even tensions within a text. Divine inspiration assumes a fundamental unity across the entire Bible. But Ehrman brackets off divine inspiration of the text to the side in order to investigate the text, ditching the Bible’s underlying unity in the process. For Bart Ehrman, the Bible ultimately has contradictions in it that can not be successfully resolved, particularly if someone has a blind adherence to a most wooden kind of divine inspiration, which tends to look the other way when bible difficulties are mentioned.

For example, Ehrman would probably conclude that Paul’s teaching about the resurrection and the end times in 1 Corinthians 15:23-24 (ESV) can not be easily harmonized with John’s vision about the millennium in Revelation 20 (ESV). He would see these two passages in the New Testament as flat-out errors, contradictions which make the claim of the divine inspiration of the Bible to be utterly incoherent (For a more evangelical way of resolving this difficulty, see this previous Veracity blog post on the millennium).

At one level, Bart Ehrman has a point. Not all harmonizations are created equal. Some ways of finding harmony within Scripture are better than others. Some harmonizations are purely ad-hoc. These ad-hoc readings are just interested in trying to eliminate possible contradictions without any regard for why the Scriptural tensions exist in the first place. On the other hand, other superior efforts at harmonization take more seriously the type of genre and literary purpose the author had in mind.

Bart Ehrman’s Case Against Pre-Trib Rapture, Pre-Millennial Dispensationalism: the “Left Behind” Theology

In the case of Hal Lindsay’s dispensationalism, the glue which holds Revelation together is the Seventy Weeks prophecy of Daniel 9, which suggests the seven-year tribulation period following the “rapture.” A linchpin is a pin in the axle of a wheel to keep in place. If you remove that pin, the wheel will eventually collapse. Likewise, the dispensationalist interpretation of Daniel 9’s Seventy Weeks is the linchpin which holds the message of the New Testament together, particularly when it comes to the end times. If that pin stays in place, it is a fairly coherent system for reading the Bible. But if you weaken or remove that pin, that whole scenario of how to read the Book of Revelation tends to fall apart. Nevertheless, the staying power of dispensationalism is the insistence of an undefined time gap between the prophetic events described in the first century and the timing of the “rapture,” which signals the start of the subsequent seven-year tribulation. This undefined time gap works as it is extremely difficult to falsify.

This time gap has a built-in resistance factor that avoids date setting, despite efforts by some dispensationalist advocates to try to circumvent that resistance factor and cheat, making certain predictions themselves while simultaneously denying much if any responsibility for being wrong about such predictions. The most infamous false prediction in recent times was when Harold Camping predicted the date of the “rapture” to be in 2011 or 2012, spending millions of dollars of donors’ gifts to advertise the coming Judgment Day, only to finally admit that he got the expected date wrong, just a few months before he died.

Then there is the problem with the concept of the pretribulational “rapture” itself, which divides the event of the Second Coming of Jesus into two separate acts, with the seven-year tribulation separating them. The first act is whereby Christians are “raptured,” to go up and meet Jesus to be taken up into heaven, whereas those who are “left behind” must endure the seven-year tribulation.

The second act is when Jesus actually enters the earthly scene to finally establish his full rule and reign. Christian readers of Armageddon, who hold to the “left behind,” “pretrib” view, and base it on a particular reading of Matthew 24:36-44, will have to face up to the reality made by scholars such as Ehrman that this passage emphatically argues the opposite of the “pretrib” view.

While there are other passages from Scripture that could be used to support a “pretrib” rapture, like 1 Thessalonians 4:13-18, Ehrman rightly shows that Matthew 24:36-44 should not be one of them. Matthew 24:36-44 argues that you should want to be “left behind” in order to avoid the judgment of God. Attempts to try to harmonize Matthew 24:36-44 with the popular “left behind” interpretation are hopelessly ad hoc and self-defeating. The only way harmonization has a chance of successfully working with a pretrib rapture view is by assigning Matthew 24:36-44 to an event at or after Jesus’ coming following the seven-year tribulation.

Another problem with dispensationalism is that nowhere in Revelation does the book explicitly specify this seven-year tribulation. There is “tribulation” in Revelation, but how do we know that this is identical to the seven-year tribulation described in Daniel 9? We simply do not know for sure. To complicate matters even further, the seven-year tribulation is never explicitly mentioned anywhere within the other books of the New Testament.

This weakness of dispensationalism is a vulnerable gap within a certain defense of the Bible which Bart Ehrman exploits, a vulnerability of which many conservative Christians seem blissfully unaware. Still, it is possible that the “pretrib” rapture view will turn out to be correct, and prove naysayers like Bart Ehrman completely wrong. Alas, Armageddon will either place some doubts in the minds of dedicated “pretrib” rapture believers, or else encourage such believers to double-down on their beliefs. So while a “pretrib” rapture plus a premillennial view of the millennium might still remain a possibility, it does not fare very well under Ehrman’s critique.

Alternatives to a Purely Futurist Reading of Revelation

But not all Christians hold to such a primarily futurist perspective, seeing a more preterist component in the book balancing out the futurist leanings (the term “preterist” simply means prophecies that were fulfilled in the past). In these more preterist-leaning views, it is recognized that some of Revelation has at least some future in view. As those like Steve Gregg have pointed out, the so-called “idealist” and/or “historicist” views of Revelation stand between the futurist and preterist models of interpretation.

A case can be made that the Book of Revelation, if written in the 60s of the 1st century, serves to reinforce Jesus’ prediction of the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem (Luke 21:5-38), which actually happens at the end of the decade (70 A.D.), without explicitly making such a prediction within the text of Revelation itself. But Revelation does have some longer term prophetic predictions simmering in the background. Bart Ehrman finds no room for such prophetic predictions, but plenty of other scholars do.

At the minimum, these predictions would include the future return of Christ, the coming judgment, and the resurrection of the dead. While many first century Christians probably did expect the world to end within their lifetimes, it is also reasonable to conclude that God has delayed this final stage of “End Times” events to some undisclosed future time. Approaching it from this angle, the bulk of Revelation was meant to offer comfort to the Christians living through troubling times in John’s day, and not some mainly cryptic prediction of a vast array of events happening some 2,000 years plus into the future.

Bart Ehrman, on the other hand, would say that Revelation makes certain prophetic predictions which ultimately failed to come to pass. The coming judgment and the resurrection of the dead never materialized, in a timely manner. Jesus was a failed apocalyptic prophet, and the Book of Revelation fell into that same failure pattern.

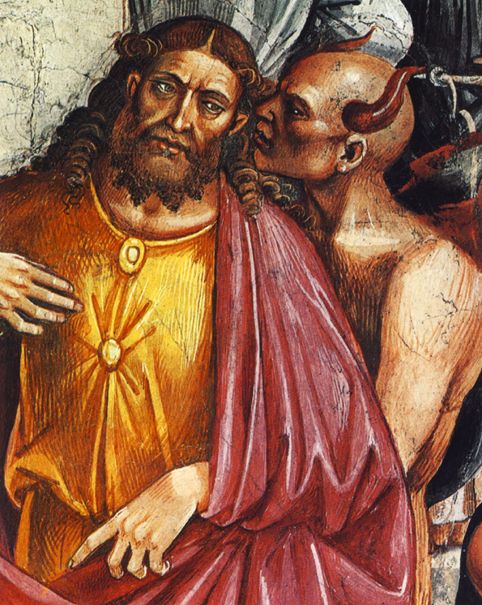

Luca Signorelli. The Deeds of the Antichrist (1499-1504). Signorelli portrays the devil counseling the Antichrist…. Interesting, the Book of Revelation never uses the terminology of “Antichrist” in the book itself. Instead, the book uses terminology like the “beast” to convey a similar concept.

Going Overboard on the Satanic Language of Revelation

In the end (pardon the pun), Bart Ehrman paints a portrait of Jesus in the Book of Revelation in a most uncharitable way as promoting a God of violence in complete contradiction with the more “loving” Jesus of the Gospels. In Ehrman’s approach, a healthy tension between the Jesus of Revelation and the Jesus of the Gospels is severed, and the contrast is stark and magnified.

Yet we can be generous and even sympathetic with Bart Ehrman to a certain degree: Part of why Ehrman paints the portrait of Jesus in the way he does is to urge people not to go to such extremes suggested by a hyper-literal reading of Revelation. Frankly, even though he takes a few wrong turns on this, Ehrman does have a point here.

If you not yet convinced by this, go read my blog article about one of Ehrman’s scholar colleagues, Dr. James Tabor, a former professor at the College of William and Mary, and his involvement in trying to find some non-violent resolution to the 1993 crisis of the Branch Davidians and the United States government in Waco, Texas. There are some truly goofy ways of reading Revelation, but they all tend to fall for some hyper-literal way of making the symbolic language of Revelation not so symbolic.

I know of Christians who like to say that they have neighbors who are effectively possessed “by Satan,” neighbors with whom they have strong disagreements with, echoing the language found in John’s Revelation. The rhetoric seems to escalate exponentially in Presidential election years.

The use of this type of language scares me. Granted, the personification of evil expressed in the Bible’s treatment of Satan is genuine. To deny the influence of Satan in our world is pure folly. However, when we overextend that language and start to demonize people with whom we find disagreement, we eventually will start to view them as enemies as opposed to fellow human travelers made in the image of God. Instead of looking for ways to then try to persuade our neighbor of the truth, we end up finding ways to reduce their humanity. We quickly forget that all of us are human, and all of us are fallen creatures in need of God’s grace and mercy.

Instead of seeking to build bridges for sharing the Gospel, we end up blowing up those bridges. We must be careful not to internalize the violent imagery found in the Book of Revelation in order to project our own judgments upon others. Sometimes we are called to intervene when others who are more vulnerable face violence from others, but we should take heed not to become that which we are trying to stop.

Instead, we must let God be the judge of others. We are all called to be accountable to God, believer and unbeliever alike. The ultimate message of the Book of Revelation, regardless of how one views controversial topics like the millennium, is to say that God is bringing about the rightful end to all of human history, and setting things straight, even though we can not fully see or understand what God is always up to prior to that end.

What Is Missing the Most From Ehrman’s Armageddon: Putting an End to Evil

This is what is missing in Bart Ehrman’s final analysis which rejects this God of the New Testament. For in the world of Ehrman’s practical atheism, there is no ultimate justice whatsoever. As I observed in my 2022 review of Ehrman’s earlier book, Heaven and Hell, Ehrman sees no compelling reason to accept the New Testament concept of the afterlife. Since there is no afterlife, there is no final judgment in Bart Ehrman’s worldview.

While some justice is served in this world, most acts of injustice never get addressed without a divine being intervening in the afterlife, which Ehrman contends is non-existent: The vulnerable are taken advantage of and their violent offenders get off with no consequences. Women are raped and their rapists are never caught, either in this world or the next. Children are killed, and their perpetrators never face the judgment of God for their actions, because in Ehrman’s worldview there is no God to judge them, and no coming moment in space and time when evil doers will face a final judgment.

Thieves rob others, leaving their victims to suffer in agony and loneliness, and these thieves simply get away with their evil deeds. For the Christian, we know that all of us are thieves like this, and yet we are thankful as believers for the grace and mercy of God to intervene in our lives. Despite living in a world of injustice, the Christian has a hope grounded in God’s grace and mercy, though the believer in Jesus knows that they do not deserve God’s generous grace and mercy.

But not everyone knows of this grace and mercy. Such thieves callously ignore the plight they leave others in, or otherwise laugh at their victim’s demise.

In Ehrman’s worldview, there is no ultimate healing for those who experience such loss. While thankfully some experience healing in this life, this is largely the exception and not the rule. Consider yourself lucky if you do experience restitution in this world. When people die, that is basically it. No afterlife whatsoever. Bad things simply happen to people and there is no final restoration to that which is good.

The Christian worldview rejects such nihilism. The Christian has a hope that others do not have. The ultimate message of the Book of Revelation is that God will eventually set the world aright, and this indeed is a good and most glorious thing, if we only have the faith to trust in Jesus.

What do you think?