During the great age of exploration of the 15th and 16th centuries, European Christians faced a nagging problem in how they read their Bibles. Traditional belief understood that all humans were descended from a single human couple, Adam and Eve, as taught in Genesis 2. But as folks like Christopher Columbus set forth on their famous journeys, they ran into humans no one ever expected. Thinking he was near India, Columbus thought of them as “Indians.” But Columbus was nowhere near India.

This created a problem: Who were these Native Americans? Where did they come from? And how did they get to the Americas?

The most popular theory that emerged speculated that these Native Americans were the descendants of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, the people of the biblical Northern Kingdom, which according to the Bible, was overrun by the Assyrians, over 700 years before Jesus was born. A common example can be traced back to 1660, when a New England Puritan missionary to some of these Native Americans, John Eliot, helped to spread this idea, to English settlers coming to the New World.

Then there was a well-known 19th century attempt to solve this problem. A New York treasure hunter had a read a book by an American Congregationalist minister, Ethan Smith, View of the Hebrews, that explored this possible connection between the Native Americans and the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, in considerable detail. Yet this treasure hunter, Joseph Smith, was to popularize this view through his translation of the Book of Mormon, capitalizing on the same theme, and thereby creating a uniquely American sect of Christian religion. Aside from the Mormons themselves, no one takes this view seriously today.

Most researchers conclude that the ancestors of today’s Native Americans came across the Bering Straight from Russia, within the past 35,000 years, but probably no less than roughly 16,500 years ago. So, does this mean that the Bible got it wrong, when it came human origins?

The Naming of the Animals, by John Miles of Northleach 1781-1849 (media credit: sothebys.com). Adam named the animals, but were there any other humans existing at the time, who were not in the picture (outside the Garden, in the Americas?)

There is more to the story. The efforts of Ethan and Joseph Smith (not related), were preceded in the 17th century by French theologian Isaac La Peyrère. La Peyrère, who had a Marrano Jewish background, was originally a Calvinist, though he later converted to Roman Catholicism. La Peyrère’s proposal endeavored to solve some persistent problems in biblical interpretation, in the process of explaining the origin of peoples like the Native Americans.

Isaac La Peyrère’s Biblical Reconstruction of Human Origins

In Genesis 4 we read that after the murder of his brother Abel, Cain obtained a wife and built a city. But the text gives us no description as to where his wife and the population of this city came from. Many Young and Old Earth Creationists propose Cain must have had a sister, another unknown child of Adam and Eve, and that Cain must have married her. But this introduces yet the strange difficulty that God might have changed his moral law to allow such an incestuous relationship to take place. For Christians today, who believe that God’s law prohibiting same-sex relations never changes, such an exception to incest, in the case of Cain, is problematic.

La Peyrère concluded that there must have been a human population existing alongside Adam and Eve, from where Cain could have obtained his wife. La Peyrère appealed to another biblical passage to further his case. In Romans 5:12-14 (ESV), we read:

- Therefore, just as sin came into the world through one man, and death through sin, and so death spread to all men because all sinned— for sin indeed was in the world before the law was given, but sin is not counted where there is no law. Yet death reigned from Adam to Moses, even over those whose sinning was not like the transgression of Adam, who was a type of the one who was to come.

The troublesome phrase here is highlighted. Who were those whose sinning was not like Adam’s transgression? What was the Apostle Paul talking about here? La Peyrère suggested:

- “if Adam sinned in a morally meaningful sense there must have been an Adamic law according to which he sinned. If law began with Adam, there must have been a lawless world before Adam, containing people” (Almond, Philip C. (1999). Adam and Eve in Seventeenth-Century Thought. p. 53)

La Peyrère’s solution was to challenge the long-held traditional view, that the creation of humans on day six, in Genesis 1, was the same event as the creation of Adam and Eve, in the garden of Eden in Genesis 2. It has been long recognized that syncing up the events on day six of creation, in Genesis 1, with the events described in Genesis 2, is not without difficulty (I go into detail in this previous Veracity blog post).

La Peyrère proposed that Genesis 1 speaks of the creation of a human population, and that these humans pre-existed Adam and Eve. Specifically, Genesis 1 has no mention of a single couple being created. These humans were the start of the Gentile, or non-Jewish peoples.In Genesis 2, Adam and Eve, on the other hand, were the start of the Jewish people, from whom the Messiah would come to redeem the world.

La Peyrère further went onto suggest that these Gentile peoples in Genesis 1 eventually became geographically isolated the Adam and Eve descendants, and eventually unknown to Adam and Eve’s progeny. So, when we get to the story of Noah and the flood, La Peyrère argued that the great flood was local in scope, wiping out the then known humanity of Adam and Eve’s descendants, and thereby not touching the other unknown humans who had migrated elsewhere around the globe.

Even though La Peyrère made a clever proposal, Jewish, Calvinist and Roman Catholic theologians of his day condemned La Peyrère’s “pre-Adamism” as a heresy. His 1653 book on the subject, Præadamitæ, was burned in an effort to censor his views. La Peyrère escaped the death penalty himself by supposedly retracting his views, though copies of his book have survived.

In view of events in subsequent years, the theologians of the day were probably correct in rejecting La Peyrère’s teachings (La Peyrère had other peculiar ideas that caught the attention of the enlightenment philosopher, Baruch Spinoza, one of the fathers of modern skepticism). Furthermore, in the 19th century, scientists used pre-Adamite theories about humanity, like that taught by La Peyrère, as a justification for racism. Before the rise of Charles Darwin, many scientists believed not in one human race, but rather, in multiple human races, who were distinguished based on the color of a person’s skin. Defenders of Christian orthodoxy were surely right in rejecting such views.

Despite whatever disagreements many Christians have with Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, both Darwin and the Bible share the common view that humans, of all colors, shapes, and sizes, share the same humanity. As a result, no scholar today would contend against the notion that we all share a common humanity.

However, other, modern developments in evolutionary biology complicate matters, when it comes to trying to synchronize science with a traditional interpretation of the Scriptural text. For example, we have continuing questions about the presence of hominids, or pre-human creatures, like the Neanderthals. Where do they fit in the Bible’s story? Archaeological research today suggests that modern humans rose out of East Africa, and not, strictly speaking, the Middle East. Then there is the research on the human genome, for which many genetic scientists argue that the earliest human population had upwards to 10,000 individuals… and NOT 2!

In view of these developments, some Old Earth Creationists, and even perhaps Evolutionary Creationists, look to some elements of La Peyrère’s work today as a potential solution. For example, Genesis 1 could be understood as referring to humans originally created in East Africa, some of whom eventually migrated to the Middle East, the traditional location of the Genesis 2 narrative. Furthermore, if La Peyrère is correct, then there is effectively no difficulty in associating a Bering Sea crossing of the ancestors of the Native Americans, to populate the Americas over 10,000 years ago, and no need to appeal any “Lost Ten Tribes of Israel” proposal as an alternative means of explanation. As with a lot of things like this, research in these areas have a speculative component.

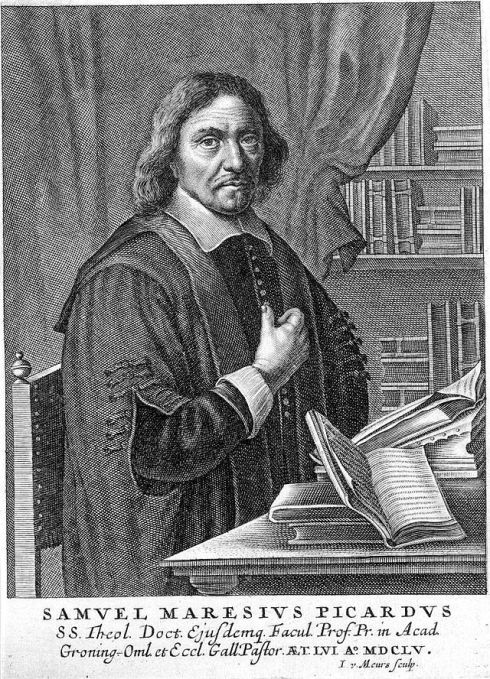

Isaac La Peyrère (1596-1675), who wrote under the pen name of Samuel Maresius. Some find him as a precursor to modern biblical criticism, but others see him as a pious scholar, who sought to solve a nagging problem in biblical chronology. He was also known as an early proponent of a type of Christian Zionism, believing that the returning Messiah would join the king of France, to set up rule in Jerusalem, and rebuild the Temple.

An Objection to La Peyrère: How to Interpret Genesis 3:20?

For example, one of the most serious problems with La Peyrère’s proposal is with Adam’s naming of Eve, in Genesis 3:20 (ESV), that “she was the mother of all living.” For many students of Scripture, this single verse makes La Peyrère’s proposal of other humans living before and alongside Adam and Eve, a non-starter. Traditionally, this verse has been assumed to teach that every human person ever born, was and is, a physical descendant of Eve, herself. But is this interpretation the only possible way of reading this text?

For example, taking this verse too literally would be absurd. Does the text really mean that every living thing comes from Eve, like every plant and animal? Surely not. Adam was already living, by the time Eve came along, so it makes no sense to say that Eve was Adam’s mother. There must be some limitation, or qualification, to the notion of Eve being “the mother of all living.” Unfortunately, the text does not spell that out for us.

As it turns out, different translations of Genesis 3:20 might give us a different clue as to how this verse should be interpreted. For example, in the NIV 2011 translation, we read the whole verse as: “Adam named his wife Eve, because she would become the mother of all the living.” Taking this in a reasonable, yet still strictly literal fashion, the highlighted “would become” might imply that Eve is the mother of all who would come after her, but not the mother of all humans, already living at the time Adam named her. Or it could be that Eve “would become” mother of the Israelite line of humans. Or it could be that Eve “would become” the mother of all living, say at a future point in time, such as when Jesus Christ comes as the Messiah, which would be quite relevant for the Apostle Paul, when in Romans 5, Paul argues that Adam was the type of the one who was to come, namely Jesus.

Furthermore, it could be interpreted that by naming Eve, as “the mother of all the living,” Adam was uttering a rebellious statement against God’s curse, that had little to do with the reality of the situation. Other scholars suggest that Adam’s naming of Eve was instead a sign of faith, that through Eve she would be the bearer of children. To make this even more complicated, some early Jewish commentators link the name “Eve” with a similar Aramaic word for “serpent,” implying that Eve was the deceiver of Adam, a designation that the narrator of the story reinterprets.

Some of these interpretative options are better than others. The traditional argument, that Adam and Eve were the parents of all humans to have ever lived after them, was is one of the better options. But it is not a slam dunk. Either way, the exact meaning of saying that Eve was the “the mother of all living” remains unclear.

For those who wonder how the ancient story of Genesis might be correlated with the discoveries of modern science, La Peyrère’s ideas might be worth considering. There are still questions out there that are difficult to answer. Nevertheless, the bottom line should be evident: Those who insist that science somehow “disproves” the Bible can be safely set aside.